Coding Literacy

How Computer Programming

Is Changing Writing

By Annette Vee, MIT Press, 2017

Review by Brandee Easter, University of Wisconsin-Madison

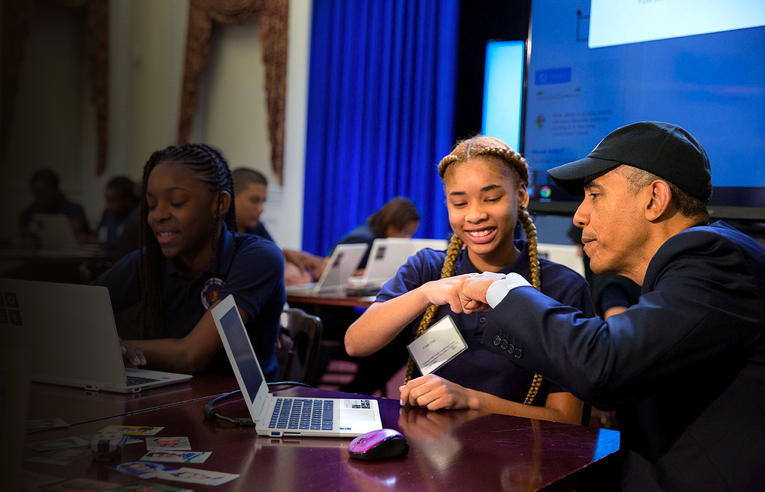

In his 2016 State of the Union Address, the first initiative President Barack Obama introduced was “helping students learn to write computer code” because this skill had become necessary for economic and individual advancement. Just two years previously, Obama—or, the ”Coder in Chief” as he was known during Code.org’s Hour of Code challenge—became the first president to write code, and his participation and call for national efforts to teach programming signals the reach the coding literacy movement has achieved (Mechaber, 2014). Annette Vee’s Coding Literacy: How Computer Programming is Changing Writing begins with these campaigns for everyone to learn to code to consider how programming is being positioned rhetorically, historically, socially, and culturally as a literacy, advancing an important call for scholars outside of computer science to attend to programming.

Coding Literacy contributes to growing interdisciplinary conversations around the computational structures that are increasingly ubiquitous and invisible in our lives. This attention can be seen in the developments of interdisciplinary fields studying programming languages, including digital rhetoric (Bogost, 2007; Brown, 2015; Eyman, 2015; Losh, 2009), software studies (Chun, 2011; Cox & McLean, 2013; Montfort et al., 2012), and critical code studies (Marino, 2006; Sample, 2011). However, Vee’s literacy-based approach makes a distinct contribution to these conversations, uncovering what programming’s rhetorical and historical positioning as a literacy reveals about ideologies behind it. She further contributes to scholarship on digital literacies in literacy studies (DiSessa, 2001) and composition and rhetoric (Gee, 2014; Wysocki & Johnson-Eilola, 1999), by showing how the rise of programming is changing literacy itself. In the book’s major contribution for both conversations, Vee shows how programming and literacy are mutually informative because as programming takes on the power of literacy, literacy also changes through the emergence of programming.

In the introduction, Vee contextualizes the coding literacy movement with traditional literacies to show how programming, like reading and writing, is emerging as a necessary skill. Although there are many emergent digital skills, she develops the concept of a platform literacy to explain how programming, like writing, is different because it structures all other skills we sometimes call digital literacies. By viewing programming from the perspective of literacy, Vee provides useful historical, social, and theoretical lenses for understanding coding’s contemporary contexts. Alternately, by viewing literacy from the perspective of programming, Vee argues that we can see literacy at a critical transition point and anticipate future directions. These stakes for literacy scholars are even greater when considering how programming’s infrastructural ubiquity makes the question of who has coding literacy a pressing social justice issue.

In the first chapter, "Coding for Everyone and the Legacy of Mass Literacy," Vee examines coding literacy campaigns to show how programming is rhetorically positioned in popular discourse as a literacy, especially as a moral, technological, or individual “good” (p. 45). Although this appears to be new, Vee traces these campaigns’ origins to the 1960s development of BASIC, which was designed to increase access for non-specialists, such as students. Vee identifies four central arguments of coding literacy campaigns: “individual empowerment; learning new ways to think; citizenship and collective progress; and employability and economic concerns” (p. 45). By looking at how programming has been rhetorically positioned, this chapter illustrates programming’s shifting social value and position in 21st century education and individual lives. Because of the rhetorical power of literacy—”if enough people call something literacy, it becomes literacy”—, Vee shows how the risks of being left behind come from not only the particular set of skills programming includes but also the rhetorical force of literacy itself (p. 51).

Chapter two, “Sociomaterialities of Programming and Writing” further connects programming and literacy, but is careful not to collapse them. Using Andrea diSessa’s concept of “material intelligence,” Vee argues that programming, like writing, is part of contemporary knowledge construction by making certain kinds of thinking more available (p. 96). However, Vee is careful to steer away from the technological determinism of autonomous theories of literacy by linking the social with the material. Through this sociomaterial approach, this chapter considers how programming, like speech and writing, are social, symbolic systems of communication that differ in audience, context, function, and thus, the types of thinking they allow. Programming, in particular, is well suited to reveal knowledge about procedures. Through pointing to differences in what programming and writing allow as material intelligences, Vee argues against a conflation that would assess programming by the standards of writing, and vice versa. Instead, this chapter ends by exploring the affordances of programming to be scaled up, offer interactivity, reach widespread audiences, and allow new forms of creative expression.

Chapters three and four seek to provide a more historical perspective to our own literacy moment: “when code is infrastructural but the ability to read and write it is not—yet” (p. 39). Each chapter reads the emergence of programming through a moment of profound transition in the history of textual literacy to show how, like writing, programming is “entering literacy” (p. 39). Chapter three, “Material Infrastructures of Writing and Programming,” traces a parallel history between writing’s emergence as a necessary material infrastructure in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries and the rise of programming in the mid-twentieth century. Together, these histories show how bureaucratic information needs provided roots for material intelligences to become literacies. Chapter four, “Literacy for Everyday Life,” examines the rise of mass literacy in the eighteenth to twentieth centuries to consider how literacies move from institutions to individuals. This history serves as a lens for our current moment, as people find themselves surrounded by computation in their offices, homes, and even on their bodies. Through this comparative history, Vee shows how, as writing created a “literate mentality,” programming is spurring a “computational mentality,” with programming becoming an increasingly less specialized and more necessary skill for individuals.

Coding Literacy is an important contribution for revealing the necessity of humanities and social science scholars to attend to programming. Vee makes clear that although programming may not yet fully be a literacy, scholars would benefit from approaching it through this lens to better understand what trajectory programming might take as well as understand how literacy is changing. Because of the rhetorical and material force of literacy, the stakes of leaving this research to computer science alone are too high. In particular, viewing programming as a literacy highlights the importance of social justice focused scholarship, and Vee’s development of platform literacies provides a useful concept for further study on the ever-increasing demands on our digital skills.

References

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. MIT Press.

Brown, J. J. (2015). Ethical Programs: Hospitality and the Rhetorics of Software. University of Michigan Press.

Chun, W. H. K. (2011). Programmed Visions: Software and Memory. MIT Press.

Cox, G., & McLean, C. A. (2013). Speaking Code: Coding as Aesthetic and Political Expression. MIT Press.

DiSessa, A. A. (2001). Changing Minds: Computers, Learning, and Literacy. MIT Press.

Eyman, D. (2015). Digital Rhetoric: Theory, Method, Practice. University of Michigan Press.

Gee, J. P. (2014). What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy. Second Edition. Macmillan.

Losh, E. M. (2009). Virtualpolitik: An Electronic History of Government Media-making in a Time of War, Scandal, Disaster, Miscommunication, and Mistakes. MIT Press.

Marino, M. C. (2006). "Critical Code Studies." Electronic Book Review.

Mechaber, E. (2014). "President Obama Is the First President to Write a Line of Code." Retrieved from White House Archives

Montfort, N., et al. (2012). 10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1));: GOTO 10. MIT Press.

Obama, B. (2016). "State of the Union Address." Retrieved from Medium.com

Sample, M. (2011). "Criminal Code: The Procedural Logic of Crime in Videogames." Digital Humanities Quarterly. Retrieved from DHQ

Vee, A. (2017). Coding Literacy: How Computer Programming is Changing Writing. MIT Press.

Wysocki, A. F., & Johnson-Eilola, J. (1999). "Blinded by the Letter: Why Are We Using Literacy as a Metaphor for Everything Else?" In Hawisher, G., & Selfe, C. (Eds.), Passions, Pedagogies, and 21st Century Technologies. Utah State UP.