From

the instructor’s perspective, one of the appealing features of Blackboard is

the ability to make students and their work visible—to us, to them, and to their

peers. Once a student has submitted an essay through the digital dropbox, it

can be easily accessed again, as can the returned draft with our comments. If,

during a conference, we need to look back at an earlier essay in the course,

it’s as available as the World Wide Web. To keep students thinking about the

course while they’re not in the classroom, we use the Discussion Board, on which

students keep up an on-going dialogue about issues related to the course. And

if we’re unsure about whether our students have been looking at the syllabus

or at newly posted assignments, we can check the statistics page and see who

has looked at the course site, how often, and at what time.

In a process-based composition

course, such visibility holds

out the tantalizing possibility of self-reflection. Students can chart

the progression of their ideas from the syllabus to the discussion board to

the draft, from peer review to editing and proof reading. They can become aware

of their own mental processes and of the social context in which they write,

seeing themselves not as isolated monads but as members of a larger group. They

can easily access past work, which remains available to them whether they are

in their dorm rooms or at a writing center. Each stage imprints a virtual path

on the ever-expanding course site so that students may retrace their steps and

think about how their ideas are formed and presented. ![]()

When such transparency becomes a governing force behind our pedagogy,

however, we have left behind Bachelard’s suggestively intimate house, replete

with its darkened crevices, niches, and closets, and have moved into an illuminated

one in which students’ work and even their work habits are open for inspection.

The question, then, is how seriously we ought to take Foucault’s (1979) admonition

that “visibility is a trap,” that it is the precondition of disciplinary mechanisms

(p. 200). Given the surveillance functions of Blackboard, it is tempting to

read this electronic space metaphorically in terms of its carcereality rather

than domesticity, panopticon rather than house. Joseph

Janangelo (1991), for instance, argues that although composition teachers understandably

seek ways to monitor students’ behavior and progress, “what is different about

computers is that they present new ways for teachers to watch students—ways

in which students can never be sure if and when they are being seen. This new

technology, which gives us an invisible yet comprehensive vantage point from

which to see students, also constitutes

‘a new economy…of the power to punish’ (Foucault, 1979, p. 89)” (p. 51. See

also Warschauer 1997). In the specific case of Blackboard, this Foucauldian

reading calls attention to the visibility, containment, and ubiquity

that occur in potential if not always in practice. Blackboard makes visible

students and their work; it contains the unregulated and undisciplined space

of the web; and it renders itself ubiquitous, both to students and to their

instructors.

According to Foucault (1979), containment is both the goal and also the

condition of possibility for a disciplinary mechanism. “Discipline sometimes

requires enclosure, the specification of a place heterogeneous to all

others and closed in upon itself. It is the protected space of disciplinary

monotony” (p. 141). Unlike the old prisons, with their semipermeable walls and

chaotic populations, the penitentiary rigorously separates inside from outside,

the prisoners from one another. Space must be contained so that it can be petitioned

and evaluated. “Each individual has his own place; and each place its individual….

[Disciplinary space’s] aim was to establish presences and absences, to know

where and how to locate individuals, to set up useful communications, to interrupt

others, to be able at each moment to supervise the conduct of each individual,

to assess it, to judge it, to calculate its qualities or merits. It was a procedure,

therefore, aimed at knowing, mastering and using. Discipline organizes an analytical

space” (p. 143).

In

Blackboard, the space that is initially organized is not physical (the prison

apart from the outside world) but virtual (the course system apart from the

rest of the web). For instructors no less than for students, Blackboard

is alluring because it is web-based yet also web-resistant. Students are confronted

not with the World Wide Web but with a syllabus, not with an open system of

infinite links but with a closed system of a single course. And it is within

the contained space of the course management system that the disciplining of

the student occurs. It is always possible, as our students well know, to walk

from the neighborhood block of the course into the vaster city of the web, but

Blackboard encourages students and their instructors to interact in a space

whose limits are safely defined by the buttons that appear on the left side

of the screen—Assignments, Course Documents, Tools, Communication, etc.—comfortable

reassurances that the space can be known and mastered. By setting off a discrete

territory that the course claims as its own, Blackboard lets us use the web

without being overwhelmed by it; we are like travelers on sightseeing boats,

hugging the coast while priding ourselves for venturing into the ocean.

Blackboard

further evidences its disciplinary mechanism insofar as it structures containment

and organizes our students’ analytical space. Alongside

any ideological inflections such as those discussed by Selfe and Selfe (1994),

Blackboard’s practical containment of the web can foster an illusion

that that our students are working in a public space, when in fact the space

is semi-public at best. Compared to a composition classroom of fifty years ago,

in which only the teacher might see student work, the virtual classroom is likely

to seem relatively open: students can constantly discuss their ideas, drafts,

and essays with one another and receive feedback that they would once not have

received. Thus Blackboard makes it easy to take the goals of a student-centered

class one step further, potentially introducing peer response and peer critique

into every level of the composition process. It

is tempting to see this shift as enabling a move into what Marilyn Cooper, in

her essay “Postmodern Possibilities in Electronic Conversations” (1999),

calls “the multiplicity and diversity of the social world” (p.

143). But the result is not public in anything but the most restricted

sense, for it is cut off from the chance encounters with difference that the

public sphere is usually seen to entail. This apparently open student activity

is both protected and directed by the spaces that contain it. And it may, in

almost all cases, be supervised by the instructor and the system administrator.

![]()

Cooper

(1999) uses Foucault to explain how the dynamic of authority can change when

a class moves to online discussion.

A teacher who sets up a classroom discussion online is not giving or sharing power with students, but rather is performing an action that sets up a range of possibilities for action by students that is in some ways different from the range of possibilities set up by a face-to-face classroom discussion; and the actions that students take in electronic conversations—and the actions that teachers take in the resulting conversation—constitute relations of power (p. 146).

Cooper argues that these new relations of power within a contained conversation may represent a move to a more postmodern and ultimately more positive set of interactions. When we step out of the electronic discussion to consider the overall space of a course management system like Blackboard, however, we see power relations change in less liberating ways.

For

Foucault (1979), the panopticon as Jeremy Bentham envisioned it is significant

insofar as it is “a generalizable model of functioning” (p. 205), itself a broad

metaphor for disciplinary mechanisms that tend toward “the non-corporal” (p.

203). Through such a mechanism, the body is disciplined by the power-knowledge

relations that begin to define it. So it is not surprising that as space

becomes virtual in a system like Blackboard, the body is not cast aside but

is incorporated into mental discipline. If students leave campus for the weekend,

they can still access their syllabus and assignments. If they are in another

state, they can still take part in Discussion Forums. If they are not in class,

they can still chat virtually. Instructors

have access to students no matter what day of the week or what time of day.

We have found ourselves giving deadlines in the middle of the night (“I’m going

to check for your papers after David Letterman’s Top Ten List”) or on a Sunday

afternoon; after all, the computer time stamp works just as well then as at

more conventional times. As a mechanism of discipline, Blackboard enables

modes of omnipresence that are difficult to achieve with a traditional classroom.

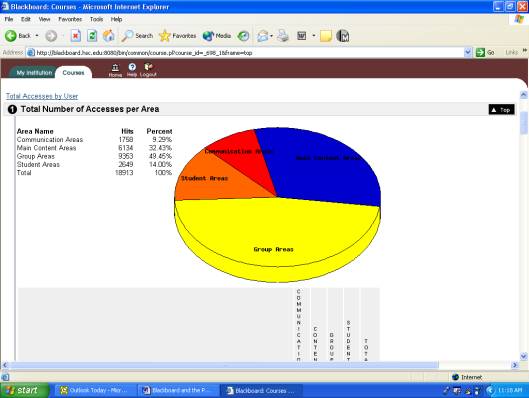

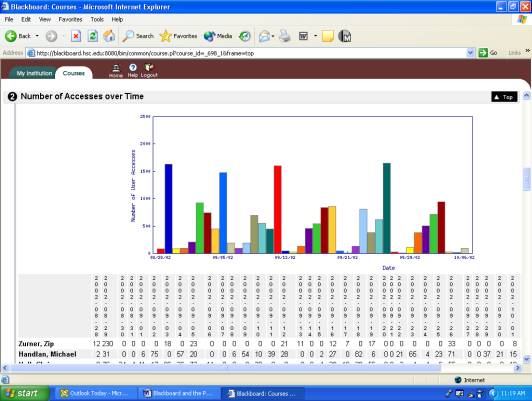

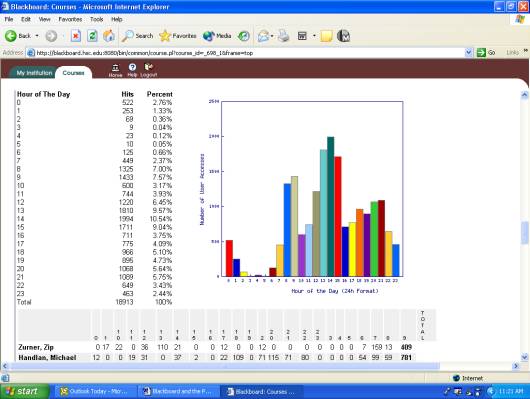

There is no more panoptic image in Blackboard than the Statistics page.

The instructor can monitor how often students have accessed the site, which parts of the site have been viewed, what times the access has occurred, and who, besides the enrolled students, has visited. The resulting dissymmetry between seen and seer extends educational discipline beyond its traditional reach. In most classrooms, we accept that only during classtime or office hours can we observe students at work; elsewhere, their time becomes undifferentiated and, to some extent, unreadable. When our students work, how often they turn to our course, whether they open their texts—these are questions that now open themselves to our inquiry and potentially to our abuse (see Janangelo 1991). Using the statistics that appear through an instructor’s site (accessed via the aptly named Control Panel), we can begin to trace our students’ interaction with our course broadly defined, not just with our classtime.

As we move our classroom community to this

space, we should not be surprised if Blackboard’s ubiquity becomes burdensome,

to us no less than to our students.![]() One of Foucault’s (1979) insights about disciplinary mechanisms is that power

in them is not localizable; the warden is no less enmeshed in a system of discipline

than the inmates, no matter how unevenly the effects of that discipline are

distributed. “Although it is true that its pyramidal organization gives it a

‘head,’ it is the apparatus as a whole that produces ‘power’ and distributes

individuals in this permanent and continuous field” (p. 177). We may well feel

caught in the middle: students increasingly come to expect twenty-four hour

access to their instructors, and at the same time, instructors find themselves

increasingly at the mercy of administrators, computer center coordinators, and

libraries who control campus-wide features of Blackboard. As the power network

expands, the centrality of the instructor is therefore doubly questioned, on

the one hand shifting towards a student-centered class and on the other tending

to one that is more administrator-controlled.

One of Foucault’s (1979) insights about disciplinary mechanisms is that power

in them is not localizable; the warden is no less enmeshed in a system of discipline

than the inmates, no matter how unevenly the effects of that discipline are

distributed. “Although it is true that its pyramidal organization gives it a

‘head,’ it is the apparatus as a whole that produces ‘power’ and distributes

individuals in this permanent and continuous field” (p. 177). We may well feel

caught in the middle: students increasingly come to expect twenty-four hour

access to their instructors, and at the same time, instructors find themselves

increasingly at the mercy of administrators, computer center coordinators, and

libraries who control campus-wide features of Blackboard. As the power network

expands, the centrality of the instructor is therefore doubly questioned, on

the one hand shifting towards a student-centered class and on the other tending

to one that is more administrator-controlled.

The

ever-present mechanism of Blackboard cannot in itself thoroughly process information,

however, even if its forms and spaces suggest that it “knows” what its users

are doing. If visibility is a trap, it is also a seductive fiction that we need

to resist. For instance, as we have noted, the course statistics page tells

us how many times each student has viewed the site, what times of day and days

of the week are most popular, and which segments of the site are viewed most

often. Such information might occasionally be helpful, if, for instance, we

want to know whether anyone has opened a document that we have posted. Yet it

is worth noting that the faint light that these statistics shed on our students

is not enough to guide our own actions. Though the numbers and graphs provide

an illusion of comprehensiveness, they track relatively unimportant information.

Moreover, students’

uncertainty about what knowledge we possess may produce more paranoia than self-discipline,

particularly when an entire faculty with its diverse computer expertise and

varying levels of statistical interest uses a CMS. ![]()

A

more specific example from a different part of Blackboard shows how its digital

information fails to capture what we as teachers really need to know. An instructor

who looks at a posting on the Discussion Board sees how many times that particular

posting has been read. Presumably, a posting that says “Read 4 times” has generated

less attention than one that has been “Read 22 times.” But though the number

appears to be useful, it levels several important distinctions. It does not

say who read the posting, so that

a single obsessive student wanting to reread his own post may be responsible

for all twenty-two of the readings. It also embodies a curious feedback: an

instructor who checks the number will in the process increase it. If, as we

prepare for class, we read the postings, we add to the number of times that

the posting has been read, and if we click through earlier postings, then we

continually add to their statistical importance. When we later see that a posting

has been read repeatedly, we may overlook the fact that the reader is the instructor.

But the most important leveling involves the word “read.” Blackboard cannot

tell what happens to the posting when it is activated, so that a cursory scan

registers the same as a detailed reading. Ideally, we want to know not simply

how many times a posting has been activated, but what how that text has been

read, manipulated, or neglected, and it is precisely that kind of information

that we don’t receive. If we ignore the problem, then we can be lulled into

a false sense of the information’s usefulness.

Despite its ready applicability, the metaphor of Blackboard as a panopticon may finally seem overstated. This is not simply because, even in a required freshman composition course, our students are not prisoners and our classrooms not penitentiaries. Rather, the metaphor falls short insofar as it explains both too little and too much: it fails to account for those shaded spaces in Blackboard where students are not on view and where their text does not leave traces, and it implies a brightly lit transparency where there more often exists a faint glimmer. But this metaphor does serve to remind us that the way spaces are structured, even (and perhaps especially) if they are virtual, alters significantly the relations of power and knowledge in the communities that use them.