Research Instruction at the Point of Need: Information Literacy and Online Tutorials

of Research Instruction

and

Tutorials

Teaching

Research

for

Designing Tutorials

The Challenges of Research Instruction

A common solution to the challenge of teaching research strategies in today's libraries and classrooms is to ask students to watch an online tutorial. You can find them in any library—virtual or brick and mortar. Take a look at some now if you are not familiar with them. Go to Google and type in library online tutorials. Most tutorials teach general concepts regarding research. They have to because they are designed to assist the generic user much like the tutorial you might encounter on Web sites such as Amazon or Google. Tutorials are concept driven. Thousands of these tutorials are available online.

Patrick Sullivan (2004, p. 75), citing Nancy Dewald, writes that it "is best to teach concepts rather than mechanics, so that students can transfer their learning from course to course. When students understand how to search for and evaluate information resources, they will become more confident learners." While we agree with Sullivan in principle (and he wasn't talking about tutorials as much as research), we have found that in order to ground the concepts of research we must teach the mechanics of research. We find that the general, conceptual introductions to directory and subscription-database research don't necessarily help students understand how to actually use the resources that are available to them through their campus libraries (both physical and virtual). The Texas Information Literacy Tutorial (2007), which Sullivan cites as a good introduction to the Web, is necessarily quite general. Boise State University has a limited version of it, a version that never leads the student to practice research in subscription-based databases. Take a look.

Although this is just one screen of a tutorial that could take hours to complete, it demonstrates the limitations of tutorials such as TILT. Online tutorials aren't designed to tell students how to find an article on a specific subject in a particular subscription database to which their institution subscribes.

While good at providing a context and vocabulary for further discussion in class of research practices, the online and textbook tutorials don’t tell students where, on their school’s library Web site, they should go to find subscription-based databases, or if their library even has these databases. If they know about these databases, which, as we discuss in the next section, is unlikely, their understanding of which one to use, how to use it, and how to enable various features such as full-text only might still be very limited.

Asking students to conduct research, then, without any specific additional guidance, is asking them to perform several hours of confusing, somewhat tedious, and not necessarily productive work preparing to do their research, and we are asking them to do this in light of what everyone knows: anyone can simply do an Internet search using Google and have usable results in two seconds.

We suggest that students who are able to perform research on a topic that is immediately relevant to them—their writing class assignment, for example—are likely to find the experience both more useful and more relevant. In their study to determine how best to teach research skills that would be transferable from one assignment to the next, Judith Larkin and Harvey Pines (2005) found that students who completed the introductory Psychology course where hands-on research exercises were required as part of the assignments (a course, by the way, developed by a Psychology professor and a librarian), “were able to demonstrate their newly acquired skills on a separate assignment” and outperform students who had not taken such a course. The authors make the point that these integrated research skills were not generic but pointed, specific and required as part of the course. The assignments focused on requiring students to use online subscription database sources. Other researchers have made similar discoveries about the development of tutorials.

Writing in the Online Classroom, Robert Kelly (2005, p. 7) describes a series of tutorials designed by George Meghabghab. In order to determine his students’ levels of need, Meghabghab has developed two tutorials for each of the sixteen major concepts students need to master in his java programming course. In order to determine a student’s level of need, he asks them to answer a series of questions related to the concept. Once he determines which students need tutorials, he divides them into two groups: “those who don’t know anything about the concept and those who have some vague knowledge of the concept.” The tutorials that Meghabghab provides are in the form of PowerPoint tutorials. As Meghabib writes, this “delivery method also provides the appropriate level of instruction when it is needed.”

Meghabghab’s method of tutorial delivery has characteristics of some of the design principles that we developed. His tutorials appear precisely at the point of need. Meghabghab determines as closely as possible, through survey, the level of assistance his students will need. His method of assessment and delivery is as close to the point of need as possible, assisting students through his course one major concept at a time.

In our work, we aim to reproduce this principle by asking students to do research on a topic that is necessary for their coursework. Our tutorials ask students to take steps that they need to take to complete an assignment. In this way, we hope that the research activity is grounded in need, and that students will not have to take the lessons learned in an abstract tutorial and apply them to their specific areas of need. Instead, we hope to work the other way. Students learn the principles of research through focused, point of need activities, and take these lessons and apply them to other research projects.

Writing in IEEE Transaction on Education, Carol Hulls, Adam Neale, Benyamin Komalo, Val Petrov, and David Brush (2005) also describe the creation of directive, interactive tutorials. They write that the “key to design is limiting the type of tutoring and focusing on instructional challenges involving the repetition of concepts that are introduced in the course lectures” (p. 719). In order to save lecture time when they teach an introductory programming class, Hulls and her colleagues pull out certain concepts that are routinely difficult for students to grasp and make these concepts the subject of online, interactive tutorials. These tutorials are highly directive; they repeat concepts that students must understand as they learn to be programmers.

Our tutorials are based on the same principles; we offer a standardized approach to accessing various resources that students can use as they research their subjects. Students learn the differences between fee-based databases and other resources, and, perhaps more importantly, they learn the routine associated with locating these resources on our library’s Web site. It is not uncommon for upper-division students at Boise State to be unaware of the existence of these databases.

As with Hulls et al.'s students, the interactive feature of our tutorials “allows students to engage in active learning by practicing the concepts they have learned in class and in the tutorials” (p. 722). The tutorials guide students through particular research steps; they are designed so that they can be stopped, if necessary, in order for students to perform the research. In addition, students are monitored closely through their research logs (which we describe in the Research Assignments section of this essay) and given frequent feedback on their failures and successes.

|

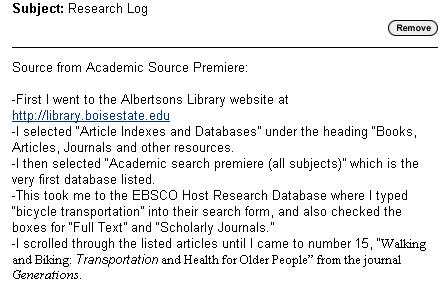

Hulls et al.'s tutorials include “self-check exercises” that allow the student to determine whether or not they’ve mastered the material presented in the tutorial (p. 719). Our students’ progress is monitored through their research logs. In their research for “Competing,” Glenda and Tom discovered that writing an assignment that asked students to perform multiple kinds of research, and providing a tutorial that demonstrated exactly what that research should look like, wasn’t enough. Many of the students continued to perform simple Google searches, apparently ignoring the instructions. It was only when they required students to submit a research log that detailed step-by-step exactly how students were accessing their information that they finally saw students using new research strategies. |

The tutorial is effective, then, when it helps students meet the goals of a specific assignment, and when students also submit research logs.

Henry Emurian (2006) and Andy Tsang and Nelson Chan (2004), teaching technical applications such as software programming have developed tutorials that conform to the same principles that Hulls et al. describe and that we follow in our tutorial development. What we have not seen, however, is this kind of directed tutorial for non-technical applications even though many of the fundamental processes are, like technical applications, straight-forward and repetitive. Recording these pieces in digital formats that can be posted to course-sites and repeatedly referred to relieves instructors of this aspect of materials development. The tutorials are directive; they ask students to follow specific routines. The tutorials encourage the students to become active learners, since they ask students to perform the routines that the tutorials have outlined. Finally, the tutorials are monitored, and students are provided with feedback on their performance.

Without realizing it, we were following some of the goals described by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE) (Developing, 2003). In order to determine a student's information literacy, the MSCHE suggests that students be surveyed as to their familiarity with, among other things, "the campus library Web site, resources available through the institution, such as EBSCO and Article First, discipline-specific online journals . . . search engines" (p. 29). The MSCHE suggests that in order to achieve the goals implied by the survey items teachers should "provide some structure for students as they begin to identify sources for assignments" (p. 31). Among other strategies for achieving this goal, MSCHE suggests using computer "labs and workshops [to] provide an opportunity to demonstrate search strategies using specialized databases, web sites, and search engines, as well as how to use discipline-specific research strategies and information technology" (p. 31).

What the MSCHE suggests, and what our research and research conducted by Emurian and Tsang suggests, is that students need significantly more structure than a library tour when they begin their research. As we describe in Instructors Teaching Research, many instructors in our small survey have experienced the same frustration as we have with the library tour. Students leave these tours without knowing how to use the available resources that the MSCHE describes and to which they have access. If an instructor works closely with students on the research portion of their essay, she works individually or with groups of students to guide them in the initial stages of their research, or, later in the process, she directs them to return to the early stages of research in order to broaden their sources. As we have demonstrated in this section, much of this repetitive work can be replaced with the information literacy tutorials that we describe.