Probiotics for Composition-Health?

Building an Ecology of Memoir Writing and Blended LearningJulie Daoud, Ph.D., Thomas More College, Department of English

<< Previous Page | Next Page >>

Blooming Where We Are Planted

The initial reading that I assigned for the composition course was Colin Beavan’s No Impact Man (2010). By the time that I introduced the book’s title and, relatedly, its quirky and cumbersome subtitle--The Adventures of a Guilty Liberal Who Attempts to Save the Planet and the Discoveries He Makes About Himself and Our Way of Life in the Process--I could detect, almost palpably—a strong student wave of ennui. While I enthused about the book, my students were discreetly diverting their attention toward their cell phones for time-checks, text-updates, and tweets. I was aware that An Inconvenient Truth had, for some, ecclipsed the issue of global warming by overpoliticizing climate science. But this wasn’t the only reason for the lack of interest. My students just did not care about what I had misjudged as a “hot-button” issue—the endangered environment.

Rather than attempt to proselytize students by cataloguing the merits of ecological stewardship (such ranting, according to pedagogical studies, contributes little to critical thinking), I asked that students volunteer what they already knew about “ecological” footprints. In other words, I invited students to contemplate the environmental “crisis” and to voice their own responses to what many environmentalists have identified as the primary exigency facing the millennial population. This open-ended prompting helped to enliven interest. Many students volunteered that they’d measured their carbon footprints in high-school; some were nonplussed by the daily-toll of their routines on the environment while others ranged from mild to moderate in their avowed concern about consumption habits . Some of the more cynical students countered that climate change was just hype; in their own experiences, they saw no evidence to substantiate the claims of scientists. And one student, Jillisa, a student seemingly poised for a major in statistics or sociology, reported that for every American child born, he/she would live to consume 25 times as many natural resources as a child born in India.

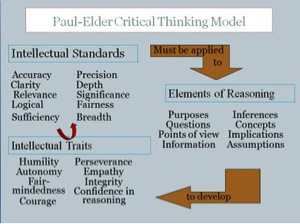

As we continued our study of the memoir over the next class meeting, we focused on a close reading of the text using the Elements of Reasoning. We considered Beavan’s purpose, the reasons that he cites for getting millennials to quit what he describes as the hedonic treadmill, his book’s assumptions about values, its implications for our quotidian actions, his argument about collective responsibility and committed grass roots action, as well as problems posed by his memoir—some of which he readily admits and other problems that readers perceive as they study the text. These seminal questions fostered rich classroom dialogue. But as much as this systematic approach to the text invited students into the conversation, I noticed that some students still lurked, tentatively, on the margins of the conversation. There was one student who, though lively in conversation before and after class, was unwilling to participate in the classroom discussion. Since I suspected that he was capable of astute analysis—he was the only underclassman starting as quarterback on the college’s football team—I was eager to reclaim what I perceived to be his lapsed attention. Careful not to put him on the spot during class, I directed a question at him through email: “How,” I proposed, “do you respond to Beavan’s ecological experiment? You’ve been pretty quiet during class. But I am truly interested in hearing your perspective.” Almost immediately, he fired back a response: “Unlike Beavan,” he divulged, “I don’t care about recycling, conservation or waste. Global warming is liberal-hype.” Impassioned, he disclosed that he “got back” at the college for gouging him on tuition increases—by taking marathon-long hot showers in the residence halls. In this way, he said, he was reaping his money’s worth at the Division III college—especially since he felt worthy of an athletic scholarship. “Ecology,” he vowed, “be damned.”

This student wasn’t alone in his resistance to the college’s costly tuition or his unwillingness to take blame or responsibility for global warming. Adrift in the challenges of college life, this young adult had more immediate issues competing for his money, energy and attention. I couldn’t pretend that he was an exception in the class of 25 students; it was fairly obvious that several students were disinterested in the memoir and had determined to get through the core course with the least amount of intellectual investment. And Beavan wasn’t the easiest person for my students—mostly middle-class students from rural Kentucky and Indiana to relate to. My students thought that this forty-two year old husband and father living in Greenwich Village was an oddity: Beavan had, after all, pledged to live without the conveniences of toilet tissue, television, and prepackaged foods—and he proudly nurtured an in-house collection of musty compost eating worms on his kitchen counter. His resolve to shut off electricity and to live life “off-the-grid” staggered my students; rather than see Beavan’s efforts as noble sacrifices, my students interpreted his efforts as abject deprivation. To them, a bubble bath was a child’s ritual bedtime pleasure and a woman’s articicial hair color, her prerogative. As my students concluded the memoir, I encountered an even more vitriolic response than I could have anticipated. The self-appointed student leader of the class, Breon, blogged that the very idea that publishing a hard-cover book to improve ecology was an irony: “This so-called ‘green-book’—which could have been abridged and circulated as an e-file—took an ecological toll as far as its manufacture and transport.” But even more importantly, continued Breon, the book “drained what to me is the most important nonrenewable resource of all: my time.”

It took me some time to recover from the surprise I felt when I read this response. Instead of lobbying a defense of the text or a justification for the hours of reading I’d asked students to invest in the memoir, I reigned in my impulse to respond to his post. I reasoned that despite the disdain the he and others felt for No Impact Man, that the memoir was proving a productive reading: the students were, after all, opinionated and impassioned. Whether they agreed or disagreed with Beavan’s initiative, they were more invested than they might have been if I’d been teaching Pride and Prejudice. As I made this resolve, I also determined that to move beyond merciless lampoonery of an easy target, I would need to redirect my teaching to propel students toward critical thinking. And this is where the blended learning model began to prove its value in my composition classroom.

<< Previous Page | Next Page >>

Footnotes

- 12 The names of students have been changed to protect their privacy.

- 13 The initial classroom discussions about the memoir were infused with the methodology for Critical Thinking promoted by the Paul-Elder model of Critical Thinking. As a participant in the college’s FLC on Critical Thinking, I’ve spent the last two years practicing a variety of heuristics associated with the Foundation for Critical Thinking.