In his 1975 work Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault warns that, in an ever-tightening surveillance state, the final stage is to become self-surveillants. Because the threat of being watched is always looming we will discipline ourselves, aligning with what our surveillants deem appropriate. In Disobedient Aesthetics: Surveillance, Bodies, Control, Anthony Stagliano extends, complicates, and resists this prediction. Stagliano asserts that Foucauldian self-discipline can no longer be considered the final stage given that the body’s very functions are now the target of surveillance. Throughout this text, Stagliano calls on Gilles Deleuze’s idea of the “dividual” and asserts that surveillance itself has become embodied – the body has become a digital medium to be surveilled. As a key theme of digital media is remix and remediation, Stagliano provides ways in which this digital medium – the body – can be remixed into subversion, obfuscation, and malicious compliance as a response to embodied surveillance. This book is organized into four main chapters: “On Tactical Rhetorical Encounters” focuses on this embodiment, “The Traffic in Faces” dedicates much of its time to post-truth and posthumanism via facial recognition, “Genome Fever” parallels Jacques Derrida’s “archive fever” with a discussion on DNA archiving services, and “Rhetorical Resolutions” focuses on malicious compliance through discussions on geo-location and hostile architecture. Stagliano opens the book with Deleuze’s call for “new weapons” but closes by stating that there are already enough weapons. He then remixes this as a call for new aesthetics and explains that “change is no longer a matter of simply displacing a troubling relation of power, redistributing the resources of a society, or of reframing the terms of a particular social issue. Rather, it is a matter of understanding the need for disobedient relationships with the dominant culture techniques of the so-called control society” (147). Here, Stagliano’s purpose is made clear: we are at the point where meaningful change can only be made through disobedient relationships, and these relationships are discussed in-depth with specific examples in this book.

ON TACTICAL RHETORICAL ENCOUNTERS

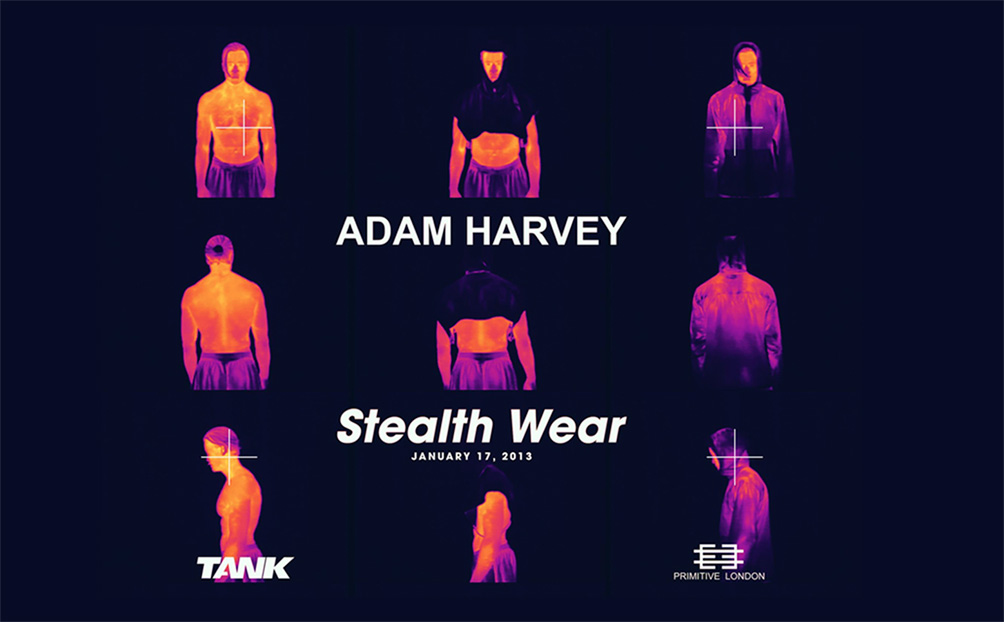

In this chapter, Stagliano merges Deleuze’s “dividual” with Foucault’s idea that surveillance demands discipline by explaining that, today, it is not discipline that is demanded of us but instead data. He describes the body as a new digital medium, and as such, could and should be remixed and remediated as any other digital medium could or should. Stagliano provides an example of this, Adam Harvey’s Anti-Drone Clothing, which reflects and thereby “blocks” thermal radiation used by drones to detect humans.

Adam Harvey's Stealth Wear - January 17th, 2013

As humans are unable to stop producing body heat through self-discipline, the answer is to subvert or pervert because “if digital rhetoric includes making computers and media systems do something other than what they are doing already, then Harvey’s Anti-Drone Clothing is a quintessential digital rhetoric project” (28). As an online writing instructor, I am reminded in this chapter of the place and space limitations put upon my online students; they cannot disengage from our institution's Learning Management System via self-discipline, but they can subvert expectations by altering their vanity/display name in their settings, manipulating data by leaving the LMS site open in the background for hours at a time, and - if instructor-approved - emailing assignment submissions rather than using LMS drop boxes.

THE TRAFFIC IN FACES

This section of the book is primarily dedicated to a discussion on post-truth and posthumanism, maintaining the focus on embodiment by centering this around the face. Stagliano notes that being in the public is no longer simply being outside of the home, as "dividual faces are virtual indices, demanded of us, imposed upon us” everywhere from using our faces to unlock our phones to Tumblr archives being scraped to train AI image generation tools (69). Within the context of the online classroom, I can parallel this to the facial recognition software that is imposed upon students, and that disproportionally affects marginalized student bodies. Stagliano’s call here is less about hiding from surveillance as it was in the first chapter, and more about obfuscation, arguing that the very technology that scares us is the same technology that will quell the concern. Our faces are already permanently public – tagged and scraped, bought and sold – and as AI-generated faces (trained by our faces) flood the internet, we become lost in a sea of post-truth, post-human faces. The more realistic these faces become, the less our real faces stand out.

GENOME FEVER

This chapter’s title speaks to Derrida’s “archive fever” by making parallels between feeding the archive loop to justify its existence and the current trend of paying to have our DNA archived by companies like 23&Me. Stagliano calls this “biorhetorical relation” the post humanist version of meaning- and- character-making. He explains that we use these services for character making because, as citizenship changes, so do the means in which we rhetorically perform that citizenship. Rather than concealment or obfuscation, this chapter points to methods of manipulation as a means to resist this type of surveillance – pointing to Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Jarad Solomon’s Bionymous, a set of guides to replace your DNA or erase your DNA. He also points to simpler methods of manipulation via "DNA spoofing" by way of swapping chewing gum, brushing the hair of others into your hair, and sharing lipstick. While this does encourage me to think of ways that I could teach my students how to manipulate their data to become entirely unusable to their surveillants, my main takeaway from this chapter is that this trend of archive/genome fever may point to a possible future direction of meaning-making in the classroom and how the dividual forms, creates, and remakes meaning. Stagliano notes, however, that as we perform a remaking of our character through encountering DNA, these services “are not just tactical exploits of the biorhetorical apparatus that underpins genome fever. They are also performative character-making exercises” (95). This notion lends itself well to a consideration of what post humanist meaning-making might look like in writing classrooms.

RHETORICAL RESOLUTIONS

This chapter opens with an example of how surveillance tools are really only open to the message that it intends to receive from its subjects. German artist Simon Weckert fills a wheelbarrow with cell phones – all of which have geo-location turned on – and pushes it down a relatively low-populated street in Berlin in 2019. In turn, Google Maps indicates a traffic slow-down due to unusually high traffic volume in the area, despite the fact that there is actually very little traffic on the road aside one man with a wheelbarrow full of geo-locators. This highlights the ways in which data interpretation shapes our world in very real ways, as traffic data is frequently used to make large-scale infrastructural decisions that impact everyone’s lives. Adding to this notion of a singular interpretation of data, Stagliano discusses hostile architecture – a controversial city planning method of keeping the unhoused invisible. Rather than attempting to understand the root causes of the homeless crisis, cities who have implemented hostile architecture instead aim to keep the bodies in circulation without room for stasis. Stillness is a necessary component of rhetorical analysis; without stillness one cannot see, understand, or adequately address the issue at hand. With unhoused bodies in constant motion, there is no problem to address. With constant surveillance and detection of students in the classroom, there is no academic dishonesty problem to discuss. Despite the fact that there are legitimate underlying causes for students to engage in academic dishonesty (e.g. lack of motivation, understanding, or resources), it is easier for institutions to keep the bodies in circulation, to keep them moving from one technology platform to the next, and to keep putting up barriers to entry so that there are no problems to be seen.

CONCLUSION

I believe that Disobedient Aesthetics is worthy of being read by those whose scholarly interests intersect rhetoric, surveillance, and media studies – and especially those who have a growing concern with the expanding use of surveillance technology in the classroom. Stagliano’s resistance methods throughout can be compared to the ways in which we can reject, reappropriate, or remix EdTech surveillance. As Stagliano notes in the first chapter, self-discipline cannot be the final stage when the body’s very functions are the target of surveillance, much like the place and space limitations of online courses in which we have no choice but to engage with certain platforms like institutional LMSs and email services. “The Traffic in Faces” reminds us of students who are forced to show their faces and glimpses of their personal lives on screen in synchronous online class sessions and online proctoring services. “Genome Fever” points to a possible future direction of meaning-making in the classroom and how the dividual forms, creates, and re-creates meaning through embodiment. The hostile architecture discussed in “Rhetorical Resolutions” mimics institutional adoption of surveillance and detection tools to keep bodies in circulation rather to understand or address the root causes of academic dishonesty. For readers of Computers and Composition Online whose interests align with these topics and issues, Disobedient Aesthetics is worth the deep dive.

REFERENCES

Blas, Z. (2012). Fag Face Mask. In zachblas.info/works/facial-weaponization-suite/.

Deleuze, Gilles. “Postscript on the Societies of Control.” October, vol. 59, 1992, pp. 3–7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/778828.

Derrida, J. (1995). Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. University of Chicago Press.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish. Pantheon Books.

Harvey, A. (2013). Stealth Wear in adam.harvey.studio/stealth-wear/.

Stagliano, A. (2024). Disobedient Aesthetics. University of Alabama Press.