Emphasizing Embodiment, Intersectionality, and Access:

Social Justice Through Technofeminism Past, Present, and Future

Julie Collins Bates, Francis Macarthy, and Sarah Warren-Riley

About

PRESENT CASE STUDY 1

PRESENT CASE STUDY 1

Technofeminist Interventions in Flint

This section of our web text argues that a technofeminist rhetorical approach to studying community activist interventions in online and material spaces enables us to hone in on the lived, embodied, and material effects of social justice exigencies facing marginalized communities. We hope that, increasingly, technofeminist work will recognize the complex, multimodal efforts of community activists engaged in local intervention. At the same time, we also argue that such technofeminist work must more explicitly engage in intersectional thinking and continue to pay critical attention to issues of access and to the ways the boundaries between online and offline activism remain necessarily blurred.

To illustrate one possibility for applying technofeminist rhetorical analysis to existing social justice issues, we offer this brief case study of community activist efforts to intervene in the Flint water crisis. The water crisis is a critical, ongoing issue in which many community activists have and continue to intervene, and thus this web text provides a limited and incomplete snapshot of a few brief examples of intervention we have intentionally chosen to highlight both the possibilities and limitations of a multimodal approach to local intervention.

Rendering a Crisis

Every time the bath water was yellow or blue or smelled funny—which was often—one of the Mays children would come running to their mother, Melissa, yelling “Mom, something’s wrong with the water again!” It happened almost immediately after city officials in the Mays’ hometown of Flint, Michigan, initiated a switch from the city’s Detroit water source to the contaminated Flint River in April 2014.

Soon everyone in the Mays family began suffering from rashes and losing their hair. The Mays children experienced a variety of additional problems likely connected to the water contamination. The youngest Mays child’s immune system was compromised. The middle child began experiencing bone pain (a common symptom of lead poisoning) and fractured both wrists in a fall off his bike because his bones were so brittle. The oldest Mays son developed holes in the smooth sides of his teeth, which his dentist believed were caused by lead exposure. All three boys also began struggling in school and suffered from memory problems and brain fog. Even the family dogs and cat fell ill and began losing fur from drinking and bathing in the water.

Tests revealed that the entire family had high levels of lead, copper, aluminum, tin, and chromium in their bloodstreams (Lazarus, 2016). In September 2014, after the city issued multiple boil advisories, the Mays family switched to bottled water for drinking, and later they began using bottled water for cooking and bathing as well.

And they weren’t alone. In the summer of 2014, after Melissa Mays developed a painful rash on her cheekbone that she later learned was a chemical burn, other community members who saw her cheek mentioned they had similar rashes, particularly in areas frequently exposed to the water from washing hands or dishes (Klinefelter, 2016).

In response to the water contamination and its effects on their bodies, many Flint residents began working at the intersections of online and on-the-ground activism. Mays was one of many residents who began calling City Hall and going to city council meetings, asking questions and raising concerns after receiving notices that Flint water was in violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act. At the same time, community members also went online to raise their concerns through websites and social media.

The water switch that precipitated the Flint water crisis was billed by city officials and the mainstream media as a necessary money-saving measure in a community that had been plagued by joblessness, poverty, property abandonment, and crime for decades. In the mid-1900s, as middle-class white neighborhoods disappeared and the city center kept growing, majority-black and working-class white neighborhoods, particularly in the city’s urban center, were largely overlooked for investment and infrastructure improvements (Sadler & Highsmith, 2016). The issue was further exacerbated when, in the 1970s and 1980s, many of the General Motors plants in the area began laying off employees and closing. By 2011, Michigan Governor Rick Snyder placed Flint under emergency management.

Many Flint residents couldn’t believe city officials would even consider switching to the “notoriously polluted” (Pulido, 2016, p. 4) Flint River as a water source because it had been a disposal site for toxic waste from nearby GM plants since the mid-1900s. Yet that is precisely what happened when, in 2014, the city’s then-emergency manager Darnell Earley encouraged the city council to save money by switching to Flint River water while the city built its own regional water authority and pipeline. City leaders prioritized the cost savings of switching to Flint River water over the health of residents. Furthermore, after the switch, they refused to listen to those residents whose bodies were directly affected by the contaminated water.

For many months after the switch, Flint residents were vocal in expressing their complaints, which went largely unrecognized or were even outright dismissed by city and state officials who insisted the water was safe to drink. As a result, many community members took matters into their own hands and sought to convey the urgency of the situation to their fellow residents, to officials, to anyone who would listen.

The artifacts analyzed in the following sections illustrate some of the many types of digital texts community activists composed and distributed in an attempt to intervene in the water crisis, and they provide examples of the types of texts we believe are worthy of learning from via technofeminist rhetorical analysis.

Expanding Notions of What Counts as Activism

Increasingly, activists from underrepresented and/or marginalized groups are combining on-the-ground activist efforts with social media messaging to enact activist agendas and counter the ways their concerns have been rendered invisible by people in positions of power. The efforts of Melissa Mays highlight how activists in Flint integrated material and digital activism in their interventionary efforts. In early 2015, when Mays realized how many community members did not yet know the full extent of the water contamination, she and her husband created a web site, Water You Fighting For. “That’s how our activism began—the web site as well as on the streets,” Mays explained in one interview (Le Melle, 2016).

The Water You Fighting For web site illustrates community activist multimodal efforts at engaging with information on the water crisis and with one another. The site offers a massive list of links to news articles, reports, official documents, and other outside sources of information about the water contamination, as well as embedded videos (some created by Mays, others culled from news segments on national television or brief documentaries created about the water crisis) and links to many local, regional, and national organizations assisting in community activist efforts. It offers much more than static sources of information, however. In particular, a chat section spanning most of the right-side column of the home page offers a place for community members to share stories, ask questions, and engage in discussion with one another. On the left column, a section titled “E-File Water Concerns” includes a form where residents can list their name, location, the specific concerns they have with their water, health issues they are experiencing, and even how much their monthly water bills are on average. Community members also can follow Mays’ social media accounts or email her directly.

Analyzing the Flint water crisis through a technofeminist lens enables us to recognize and emphasize that although there is great potential in activism occurring via online spaces such as the Water You Fighting For web site, not all efforts enacted by community members occur solely online, nor should they. Many activists combined their online efforts with on-the-ground activism because they realized that not everyone had access to the resources they were providing in digital spaces or the literacies needed to navigate them. For instance, Mays and her husband used their tax return money to print two-color door hangers that community activists distributed door-to-door to 4,000 homes in the Flint community to notify residents who may not have access to the Internet or television of the contamination (Le Melle, 2016). Such on-the-ground notifications were particularly important in many immigrant neighborhoods in Flint, where some residents who did not speak English were not aware of the water safety issues because all information from the city was printed only in English.

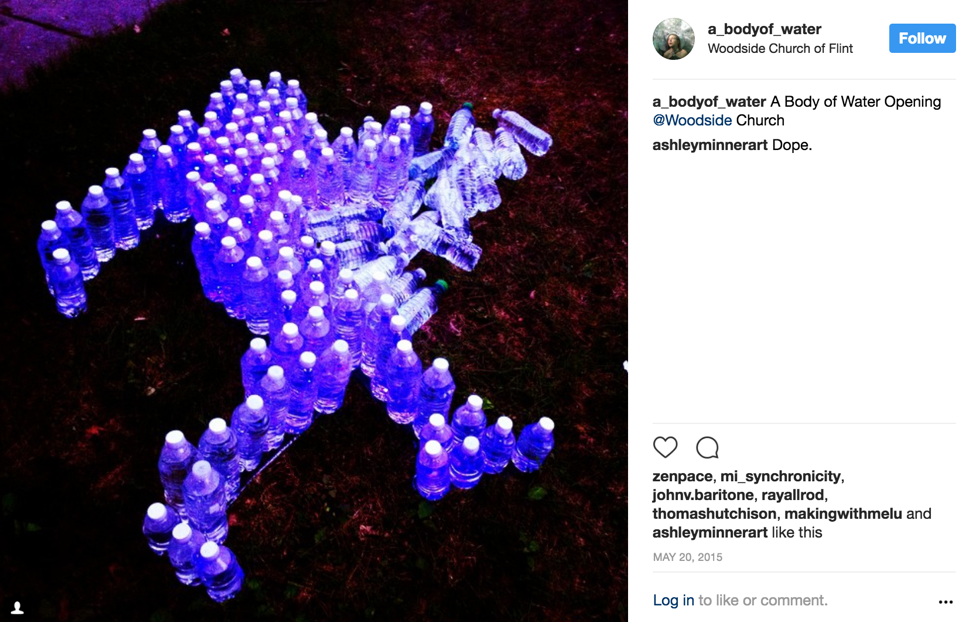

We advocate for a broad conception of what counts as “texts” worthy of study in technofeminist rhetorical analysis, even extending beyond writing occurring on web pages or door hangers. Art installations, street performances, and other material outreach also play a pivotal role in community activist interventions. For instance, in Flint, activist–artist Desiree Duell spread awareness through art. Duell’s A Body of Water installation involved community members who posed on the ground so their bodies could be outlined in chalk, similar to the outline around a body at a crime scene. The outlines were then filled with water bottles illuminated with waterproof LED lights (Tyson, 2016) to draw attention to how people’s bodies and daily lives were being affected by the contamination (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An Instagram post by Desiree Duell showcasing one of the local A Body of Water installations in Flint.

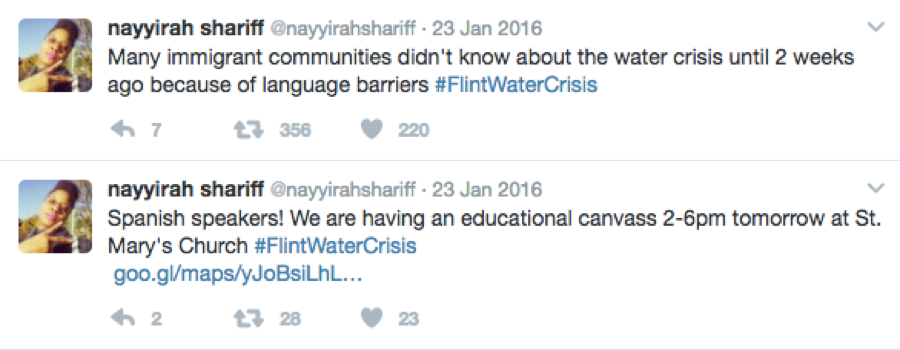

Such on-the-ground efforts rarely occurred in isolation from social media messages. Images of Duell’s installation were shared online and via social media, furthering their reach beyond the community centers, churches, and festivals where the installation appeared. And tweets by community activists like Flint Rising director Nayyirah Shariff also highlighted what was actually happening in the community. For instance, Shariff posted to inform people of where they could access safe water, to solicit help with unloading and distributing bottled water, to generate interest in canvassing to spread word about the lead contamination throughout the city, and to raise awareness when some community members who were undocumented, homeless, or did not have official forms of identification were being denied access to free bottled water at fire stations.

Figure 2. Two tweets from Nayyirah Shariff in which she discusses the need to spread word to immigrant communities about the water crisis.

Emphasizing Identities and Embodied Experiences via Social Media

Recent social and environmental justice efforts like those that occurred in Flint underscore one present approach to local intervention that can be made apparent by a technofeminist analysis. Specifically, community activists use social media to make explicit their own subject positions and make visible the effects of environmental contamination on their bodies and the bodies of family members. Some early technofeminist scholarship hailed the potential of online interactions for developing identities separate and potentially quite different from our identities in the material world. Yet today we argue that online spaces such as social media actually enable community activists to more explicitly convey their multiple, often-marginalized identities and their often-ignored embodied experiences.

Specifically, messages shared via social media, particularly Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, made apparent whose bodies were being affected by the Flint water crisis and in what ways. Many of the effects of the water contamination, such as lead levels high enough to be classified hazardous waste at some homes, were invisible. Yet community activists sought ways to draw attention to what they were experiencing as a result of the contaminated water by sharing via social media images of the discolored water coming from the faucets in their homes, the chemical burns and rashes on their skin, and other visual “evidence” of the contamination (a sampling of these posts in shown below in Figure 3).

Figure 3. Screen shots of images tweeted by Flint community members that showcase the effects of Flint water contamination on their lives. The photo at left shows a rash on a child’s back attributed to the water contamination in January 2015, the middle image depicts Flint water from August 2015, and the photo at right shows Flint children filling their tub with bottled water so they can take a bath in April 2016.

Yet such evidence is not always easy to convey, as Julie Doyle (2007) pointed out, because it involves highlighting issues that “are both temporal (long term and developmental) and unseen (not always visible), through a medium that privileges the ‘here and now’ of the visual” (p. 129). Even the photos community members shared via social media were limited in what they could “prove,” as the most toxic elements in the water (particularly lead) were invisible and so could not be seen in the images. Flint community members attempted to convey these toxic effects not immediately visible by, for instance, posting photos of upset children having their fingers pricked as they underwent lead testing or images showing all of the bottled water they had to use for bathing or cooking. Looking itself is an embodied experience, and photographs like these helped viewers connect the effects of environmental crises to their own bodies and identify with the problems Flint residents faced, whether they lived in Flint or half a world away. As Kelly Oliver (2001) argued, “to speak, to bear witness to [victims’] dehumanization is to repeat it by telling the world that they were reduced to worthless objects” (p. 89). Many Flint residents intentionally chose to share such dehumanizing images via social media. Such tools/technologies enabled community members to offer testimony of their embodied experiences with the water contamination not mediated through the mainstream media so that others might witness the real effects of the water crisis.

Other images shared via social media highlighted the actions community activists were taking in the community to make the effects of the contamination on their bodies known. For instance, in May 2016 ten women wearing white jumpsuits decorated with red-painted hearts saying “Flint” held what they called a “die-in” on the steps of the Flint water treatment plant. The paint from the hearts bled down their jumpsuits to their legs to represent the ways women’s reproductive systems were being damaged by problems with Flint water. For 20 minutes, the women lay silently on the front steps of the water treatment plant, despite repeated requests for them to leave (May, 2016). Images of the die-in shared via social media brought attention to a consequence of the water contamination that other community members may not have been aware of or that had not yet been portrayed in the mainstream media (Figure 4).

Figure 4. An @FlintRising tweet shows a photo of women in painted jumpsuits who protested on the steps of the Flint water treatment plant in May 2016. The red paint running down their legs represents the reproductive problems including miscarriages resulting from the city’s water contamination.

By distributing information about the die-in and other local protests via social media posts such as the tweet above, community activists engaged in what Manuel Castells (2012) called a “multimodal assault against an unjust order” (p. 13), in which they sought to make apparent via cyberspace and urban space the injustice of the ongoing contamination of their bodies. Many Flint community members, including those who might not have been able to attend protests because of myriad factors including work or school schedules, disability, or lack of access to transportation, took to social media to share their experiences with Flint water contamination. Additionally, numerous community activists present at local events used social media as a venue to share information and to make public complaints that were disregarded or ignored at city offices and council meetings. These community activists moved online to what Huiling Ding (2009) called a “cultural site less regulated by power apparatuses and more readily accessible to the public,” which served as an “entry point into power systems for tactical intervention” (p. 344).

In addition to raising awareness of how widespread the effects of the water contamination were within their community, activists who posted such photos and information online also expanded their reach beyond Flint, as their posts went viral and people from across the United States and around the world who may not have otherwise known about the crisis became concerned, began following what was happening in Flint, and started posting about their concerns on social media as well, which further helped increase outrage about the water crisis via social media. Such online activist efforts likely played a part in state officials’ much delayed eventual disclosure of the severity of the contamination.

The texts community activists produced online assisted in spreading the word about the water crisis within as well as beyond the Flint community, resulting in a circulation of discourse that enabled community members and other concerned parties to join forces to intervene. Research has shown that social networking can assist people in mobilizing their networks (see, for instance, Ryder, 2010), and in Flint the circulation of discourse from a combination of visual, material, and digital rhetorics led to precisely such mobilization. Sometimes that circulation—in the form of sharing, commenting, liking, re-tweeting, and so on—occurred via Web 2.0 technologies. Yet these forms of circulation have their roots on the ground—in sharing information door-to-door, commenting on others’ statements at community meetings, liking street art efforts via applause or honking from passing cars, passing along pamphlets or other written communications at rallies, and so on. In other words, community activist efforts at intervention involve similar activities aimed at circulation of texts, whether those activities occur online or out in a community. Often local interventions occur and evolve both online and in the community at the same time, as outrage prompts protests in person and events in the community are shared online via photos posted to social media. Such an intersectional approach recognizes what Henry Jenkins, Ravi Purushotma, Margaret Weigel, Katie Clinton, and Alice Robison (2006) described as the “interrelationship among different communication technologies, the cultural communities that grow up around them, and the activities they support” (p. 7). In other words, these different rhetorical tactics all work together as part of what Elise Verzosa Hurley and Amy Kimme Hea (2014) called a “larger complex of communication practices” (p. 66) undertaken by community activists in response to local environmental and social justice concerns.

Recognizing Power Relations: Who and What Shapes Intervention

At the same time we highlight just how online spaces have enabled community activists to draw attention to their embodied experiences, we caution against yet again falling into the trap of only heralding the democratizing potential of the Web. The case of Flint activist efforts discussed here emphasizes the potential for intervention via social media and underscores that how and whether interventions occur within communities is contingent upon power relations—both online and within the communities where social and environmental justice efforts occur.

This case study presents examples of how community activists used social media alongside on-the-ground activism to join together and mobilize. We argue for the importance of recognizing the intersectional identities of the activists who enacted this rhetoric of intervention, while also acknowledging that some community members were better positioned than others to engage in this work. Many community activists, including those whose efforts are briefly mentioned in this section, were able to undertake these interventions for a number of reasons. Some of those reasons stemmed from their own persistence and passion for uncovering what was happening to their bodies and the bodies of their family members. Other reasons likely have to do with their identities and their locations at the intersections of race, socioeconomic status, gender, and more. Consider, for instance, the potential effects of different races, literacies, levels of income, education, employment, and technology access among women community activists in Flint. Some of the women most widely profiled for their efforts, such as Melissa Mays, are white women able to deploy persuasively the commonplace “It’s our responsibility to protect the children.” Yet Mays and her husband also had finances stable enough to use their own money to pay for door hangers, web hosting, and other necessary costs to begin community outreach, and they had access to technologies and the technical know-how to create the Water You Fighting For web site.

We do not wish to downplay the vital contributions of activists such as the Mays. Rather, we want to recognize the intersectional identities of the community activists who enact technofeminist interventions, some of whom face more forms of oppression at any given time than others. Many community activists struggled with their own health problems and the health challenges their children faced, which limited their time and ability to engage in activist efforts. Some fit in their involvement around working multiple jobs. Others were active early on but could not sustain the engagement required for so many months. In other words, there are many reasons why some community members do not become community activists, even if their insights and approaches would be valuable and beneficial to local activist work.

To continue traveling through our web text, learn about the importance of early technofeminist scholarship to our work in the Past section, read our second Present case study on embodiment in virtual spaces, or continue to the Future section to consider the possibilities for where technofeminist intervention may move next.