You may be wondering why it is that I never sought out news on the television. Thanks to the aforementioned job and graduate seminars, I was never home from work when the national evening news came on, and I didn't have cable to watch 24-hour news networks like CNN, MSNBC, or FoxNews, although now I know that they did not have information that would have soothed my concern. And while every network website offered streaming video or audio clips from the day's broadcast, many, if not all, relied on Windows Media Player or Internet Explorer, neither of which I could get to function properly on my Mac laptop.

When searched online further, I did find the map resource Scipionus.com and an interactive Google Map (previously hosted at http://mapper.cctechnol.com), they both estimated 10.3 feet of water at my home address, but I refused to believe them. After all, I had seen no television coverage of my neighborhood, so why should I believe seemingly random numbers? By the time I saw a citizen journalist photograph uploaded to WWL-TV.com showing our local grocery store, Ferrara's, submerged and an Associated Press photograph of a body tied to a tree in front of my elementary school (a photo which is also featured in historian Douglas Brinkley's book The Great Deluge), Mayor Nagin and the National Guard had ordered all New Orleanians out of the city, so no one we knew could physically go to our house [a few blocks away from those images] and tell us exactly what they saw there.

My communications breakdown was intensifying. But I continued to look online. I knew somehow that I could trust the Internet in this situation, more than ever before.

As someone who only a few years ago used the Internet solely for email and instant messaging, my turn to the Internet as both a tool for and source of academic research has evolved over the years. You could say that I have blogged from day one of my PhD program, which began in 2003, and, immediately, I knew it was the new medium for me. After all, blogging was "all about me." Then the personal went political and I jumped on Howard Dean's Blog for America bandwagon. I wrote papers about how the Internet was being used as a grassroots machine, and then I asked my first-year writing students to blog. When I realized blogs offered a greater sense of community to my online composition students, I stopped forcing my face-to-face students to post their work to the web. After all, just because I enjoyed blogging did not mean that students would find the same benefits from it that I did.

However, when "blog" was named the most looked up word on Merriam-Webster Online in 2004, I knew that things were changing for the tool. I also knew that new tools were in development that would further impact political campaigning, teaching, and everyday life. Still, never did I expect my blog space to play such an important role to my emotional well-being; not until Hurricane Katrina hit.

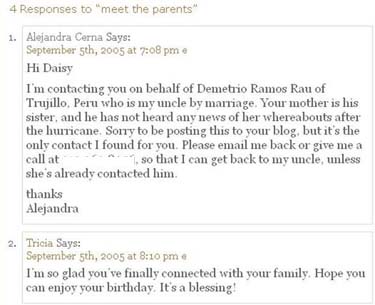

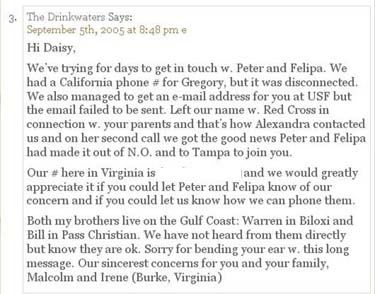

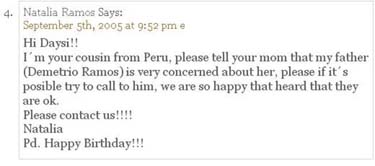

That week of the storm, when emails from concerned friends were pouring in and I had no time to reply to each one individually, I pointed them to my blog where I had started posting the little I did know. For example, in my Labor Day 2005 post I tell of my parents' arrival in Tampa and then the denial I set into, which was again prolonged by technology because, at the time, "[G]oogle earth [was]n't Mac compatible." What was most interesting about this particular post, especially to the topic of public writing that I had spent most of my PhD program researching, were the comments it received:

When I received these comments from family members I had never met and friends I had not seen since the seventh grade, I realized the true power of the Internet. How else might they have found me or known of my parents' safety other than from my blog? More pertinent a question, though not one I initially set out to answer was this: What else might I be able to learn from fellow Gulf Coast-based bloggers in the months and now years after Katrina?

Realizing that attempting to explore such a question would require a lot of time and reflection, I found myself inclined to write more traditional analyses of the ways the Internet was utilized during Hurricane Katrina. Because of the History of Rhetoric course I was taking in Fall 2005, words like kairos, logos, pathos and ethos, and dissoi logoi appeared in my seminar paper that took on former FEMA director Michael Brown's insensitive emails and offered a general discussion of how traditional media failed us during this disaster. I quickly found support for the latter opinion, which echoed my own frustration with inaccurate storm coverage, in an article by the editors of The New Atlantis entitled "The Lessons of Katrina: Natural Horrors and Modern Technology." Their review of television media during the disaster was not favorable, with their main critique being that "Television can pack an emotional wallop, in a way that the printed word cannot…with images [that] can distort truth and distract from what really matters" ("The Lessons of Katrina," 2005, p. 117). Rather, they ascertain that it was the Internet, as a medium for communication and information that "performed admirably during the disaster" ("The Lessons of Katrina," 2005, p. 117). The New Atlantis'editors continue:

While bloggers don't have the platform available to broadcast media, they did provide useful information before, during, and after the crisis–although much of it was, of course, unavailable to the people left powerless by the storm. Countless websites made it easy for people elsewhere in America (and around the world) to make charitable donations to relief organizations like the Red Cross. Aid efforts–including some spontaneously formed online–were organized and mobilized over the Internet. Several websites hosted registries of missing or unaccounted-for individuals, allowing families paralyzed by separation to regroup and make decisions about what to do next. And while the false reports from the major media were frequently repeated online, it is worth noting that the blogosphere's native skepticism has meant that much of the impetus for checking facts and correcting the record has come from bloggers. ("The Lessons of Katrina," 2005, p. 117)

This excerpt exhilarated me. I knew I could use it as a springboard for lengthier discussions and closer looks at websites and weblogs that had evolved throughout the Katrina disaster. I saw this newly focused idea evolving into my dissertation precisely because it dovetailed my own experience and built upon my affinity for public writing.

However, I denied the idea of including an extended version of my story of blogging throughout the storm because I did not feel it "academic" enough to merit discussion in the field of computers and writing. While I knew I had an original connection to the material, I doubted myself because I believed "remediation," "time," and "space," were more valid, theoretical terms from which to launch my discussion.

Thus, for another final paper in a directed study that explored Online Community and Identity, I decided that I would 1) offer examples of how web spaces were revised to address the needs of victims and 2) contrast the visual designs of those sites in order to determine how community and trust are best formed online. What was I thinking? The second objective would be nearly impossible to speculate, never mind "determine." More problematic, though, was the fact that I had little to no experience with visual design or conducting empirical research. Because I did not recognize that I did not need to label my methods right away or force myself into more commonly chosen methods, I denied myself the chance to allow my methodology to form as I went along. I returned to text-based resources, like the reports published by the Pew Internet and American Life Project.

One might think that I would have allowed myself some leeway after reading their 2001 report entitled, "The Commons of the Tragedy: How the Internet was used by millions after the terror attacks to grieve, console, share news, and debate the country's response," which documented that a significant post-9/11 development in online use was "the outpouring of grief, prayerful communication, information dissemination through email, and political commentary" (Rainie & Kalsnes, 2001, p. 2). But I didn't. Even when it described the droves of people from the New York and Washington area who turned to online communities to search for friends and family because of the overload on telecommunication systems, an act that explicitly resembled my own online searches and emotional blog posts during and since Hurricane Katrina, I had issues as a researcher. None of what I would have included to tell my story fit in to the categories described in Mary Sue MacNealy's Strategies for Empirical Research in Writing (1999) or John W. Cresswell's Research Design (2003)–not even the idea of a "mixed methods" approach.

The thought of returning to explore what I went through the week of the storm scared me when all I wanted was to remain in denial. The only way I could ever see past the labels was to recognize that I too was traumatized–traumatized not only by the loss of my home and by the physical referent of the city of New Orleans, but by the fact that everyone I had ever known had also lost everything and there was nothing I could do to help.