I record and then refuse to think about my feelings. Instead, I return to writing the details of what has occurred so far, an exercise that helps sort out what I know from what I guess and distances me from the experience. It seems sensible to make a project out of this, to pretend that something positive is happening. Writing soothes me. Recording the events frees my mind and body to relax. Knowing that the details are recorded keeps me from going over and over them, to see if I can force a different outcome. Reliving what happened just makes the situation appear worse, and then the panic returns. I do not have enough information to be sure of anything, I assure myself. I still hope for a miracle, to wake up from a dream, or to find that this is a morbid joke. (Ellis, 1995, p. 153)

The quote above is from Carolyn Ellis's book Final Negotiations, a sociological text that tells the heartbreaking story of her relationship with a man who is dying of emphysema. While it is a story of losing a partner, it is also the story of Ellis living dual lives–one of caretaker and the other of young academic. Thus, her words so fittingly apply to my experience as a transplanted New Orleanian feeling helpless yet driven to make some sense of the disaster. The thing was, though, that I considered myself incapable to write about the Internet's ability to become a site for stories to be told, information to be exchanged, facts to emerge, whistles to be blown, and acts of charity to be organized without first writing a narrative about the storm's impact upon my personal and academic lives. (See the methodology section for discussion of how the Internet as a site of research also challenged me due to it being a fluid, ever shifting narrative of its own).

Then I was introduced to trauma theory.

In her book Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Our Stories Transforms Our Lives (1999),Louise DeSalvo writes, "Often…trauma remains undisclosed because, though people would like to discuss it, they can't or won't because they fear punishment, embarrassment, or disapproval or because they can't find an appropriate audience. So, many people actively stop themselves from telling their stories; they inhibit the need to tell their traumatic narratives" (p. 24). DeSalvo explained my situation exactly. Upon meeting people for the first time, whenever I was asked, "How'd you and your family make out after Katrina hit?" I would truncate my story to a three-word response: "We lost everything." I figured that if I responded, "I couldn't find my parents for almost a week," people would think that my mother and father were like the people they saw on television, stranded either at the Superdome or Convention Center, or like those they had heard about who had to hatchet their way out of their attics. Quite frankly, I still feel guilty about labeling myself a "Katrina victim" because I didn't have to endure anything other than frustration at not having any precise information. Even my parents are better off than most "Katrina victims" due to their relocation to a second home we already owned in Picayune, Mississippi. In general, when I eventually tell people that my parents evacuated the day before the storm, I am convinced that whatever sympathy they may have had for us will diminish. And when my mind thinks that, I get angry and tend to stop talking all together.

I did, however, begin writing my story online. Turns out, I have a more open, honest, and emotional persona online. Online, I have my blog space to share how upset I am. Furthermore, during and since Hurricane Katrina, I have realized how much I prefer blogging to talking. (See my references to Bessel Van der Kolk in the methodology section to understand the application of trauma theory to this realization). Somehow it is more comforting to speak to an invisible world-wide audience than to actual people face-to-face, even my friends, parents, and fiancé. I do not have to explain myself right away as I might have to in a verbal exchange. If people have questions, they can leave a comment and I can choose whether or not I want to respond. In terms of audience, I know that my blog posts can be read by anyone, compared to an email, which can reach only those I send it to.

Trauma theorist Cathy Caruth (1995) describes the importance of audience to the types of communication linked to trauma as follows: "[T]he history of a trauma, in its inherent belatedness, can only take place through the listening of another" (p. 11). She continues: "In a catastrophic age, that is, trauma itself may provided the very link between cultures: not as simple understanding of the pasts of others but rather, within the traumas of contemporary history, as our ability to listen through the departures we have all taken from ourselves" (Caruth, 1995, p. 11). Because a blog is online and fully accessible, its level of cultural communication, as Caruth describes it, is elevated. Still, I have to wonder, that if, in conversation, I choose to diminish the hardships my parents face now as they deal with government paperwork and insurance companies regarding our New Orleans house, but then write about those hardships online, is that "better" due to the large potential audience I may reach?

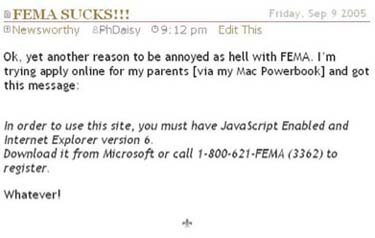

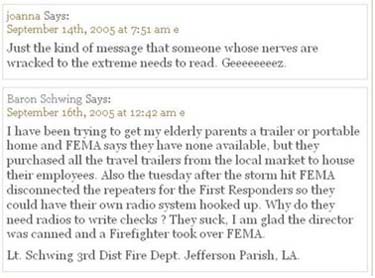

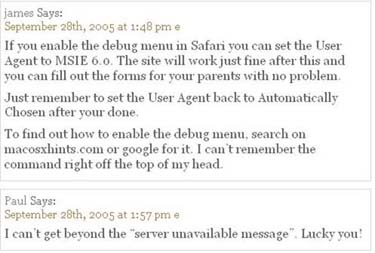

The answer to this question, as with everything regarding my imminent dissertation, is surfacing day by day. As difficult as it may be to process the details of a post-Katrina New Orleans, I do feel better once I have written something, anything. Maureen Murdock (2003), the author of Unreliable Truth: On Memoir and Memory, argues, "It is the act of writing rather than the writing itself that provides an opportunity to heal" (p. 76). Still, my blog writing differs because of the fact that it is online and thus has an infinite audience. Besides my own body and mind feeling comforted by recording what I know or feel, others may find comfort in the posts, which is another point Murdock (2003) makes: "It is true that we never know exactly what heals a person, but the greatest healing may come in knowing that from our suffering we have comfort to offer each other and that we are not, in fact, alone" (pp. 81-82). When looking back at my August and September 2005 blog posts, I have noticed how they read like silent SOSs for information; amazingly, and encouragingly, they were SOSs that were answered. Consider one of my blog posts and a few of the responses it received:

Award-winning fiction writer Margaret Atwood (2002) has said that there are "three questions most often posed to writers, both by readers and by themselves: Who are you writing for? Why do you do it? Where does it come from?" ("Introduction," p. xix). In the case of the blog post above, I was writing to vent my frustration with a PC-dominant government to anyone who cared to listen as well as to make it known that there was yet another reason to find fault with FEMA's handling of Hurricane Katrina. The post came out of the anger that a government website would neglect that segment of America that is comprised of Macintosh users, particularly a segment so obviously desperate for assistance after a disaster. If we consider those who leave comments as writers (who also answer to the questions Atwood established), their reasons for writing vary from commiserating, voicing their anger, and attempting to offer technical assistance. Hence, what my example shows is that all writers concerned in this instance felt relief after publishing their opinions with the push of a button, demonstrating yet another reason why many turn to the Internet at times of crisis.

With countless other blog posts composed and comments received over the past two years, I realized others were going online to share similar stories as well as reports of their rebuilding efforts. I immediately saw a new direction to take my dissertation. Trauma theory and literature on the theme of "writing to heal" could be combined with the research I had been compiling on the impact of blogs in the public sphere. I felt a weight lifted.

But how to define my methodology?