Results

The survey results are available here on a Google Sheets spreadsheet, though I have removed responses that included information that might identify respondents. I invite you to examine the answers yourself. My focus here in discussing the results of the survey is on how the role of previous experience influenced the survey responses, both because my research questions focused on previous experience and because I believe the results suggest a clear pattern. I did not see a similar pattern with regards to factors like gender, the faculty category and rank, or type of institution. This could be because my sample size was too small, it could be because the majority of my survey participants identified as women who or are in a tenure-track position at an institution that grants Doctorates or Masters degrees, or it could be a bit of both. I'll begin by talking about the key questions on the decision to choose to teach online synchronously or asynchronously and why participants taught in those different modes.Then I will examine the differences in the Likert scale questions based on experience teaching online prior to Covid.

Synchronous vs Asynchronous

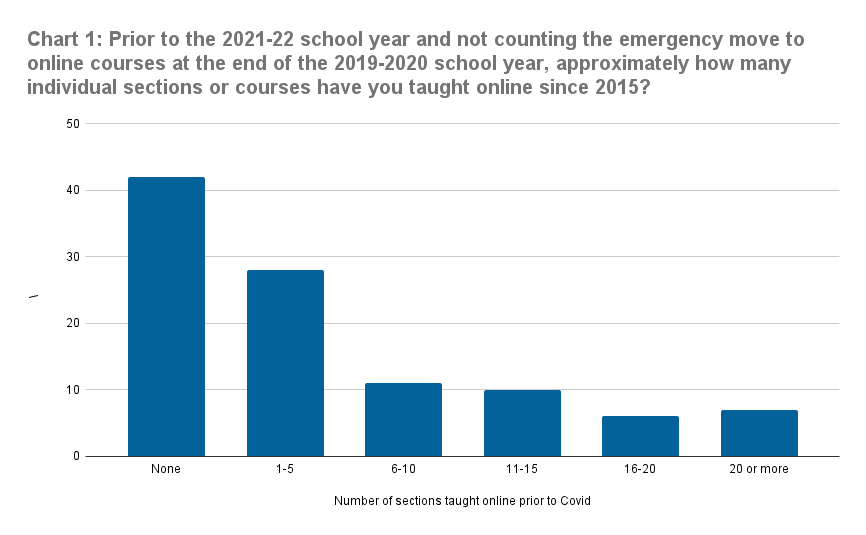

Chart 1 displays the level of experience survey participants had teaching online prior to the 2020-21 school year. Forty-two survey participants had no prior to Covid experience with teaching online, while the remaining 62 participants had taught at least one course online in the previous five years.

One of the key questions in the survey was "Which of the following best describes how you are teaching your online courses during the 2020-21 school year?" The three possible answers were:

- I am teaching all of my online courses asynchronously: that is, we do not meet as a group at a fixed time.

- I am teaching all of my online courses synchronously: that is, we meet regularly via a video conferencing software at a previously scheduled time.

- I am teaching some of my online courses synchronously and some asynchronously.

A majority of all survey participants taught at least some of their courses synchronously: 39 taught all of their courses synchronously, 40 taught some courses synchronously, and the remaining 25 taught all their courses asynchronously. But the difference between those survey participants who had had at least some experience teaching online before Covid and those who did not is striking.

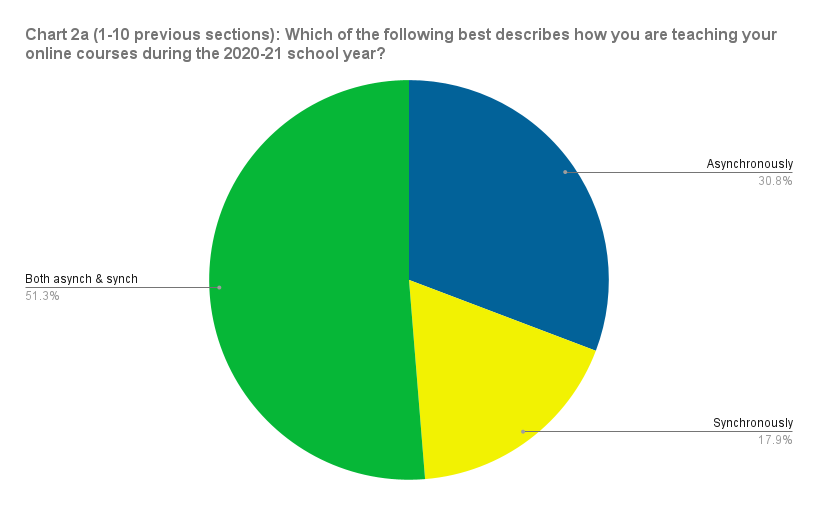

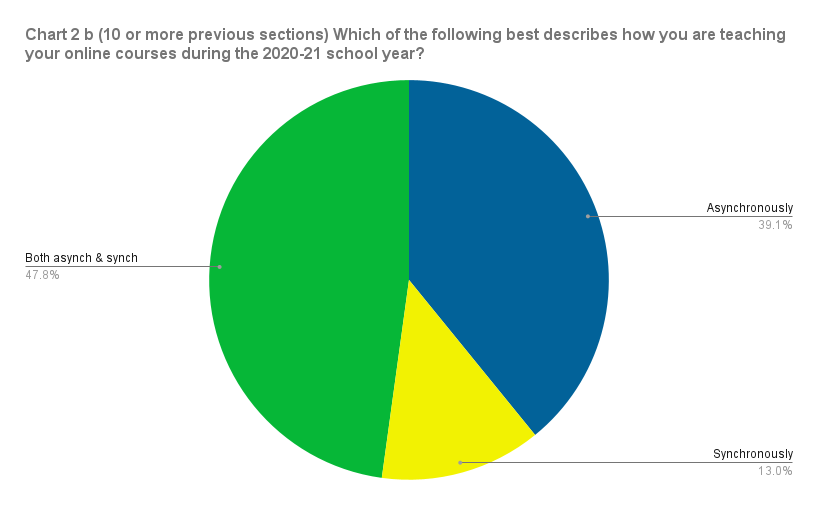

Charts 2a and 2b indicate the answer to this question for the percentage of respondents who had previous experience teaching online prior to Covid.

Because the number of survey respondents with previous experience was small, I combined responses from those who had taught 1-10 sections online and those who taught 10 or more sections prior to Covid. Thus, the 2a pie chart shows responses from participants who had taught 1-10 courses online prior to Covid, and the 2b pie chart shows responses from participants who taught 10 or more courses online prior to Covid. The percentage of respondents who had previously taught 1-5 courses online who elected to teach synchronously was slightly higher than those who had more experience teaching online, probably in part because there were more respondents with this level of experience than in the other categories. But generally, these two charts are similar: just under 31% of respondents who had taught between 1 and ten sections online before Covid elected to teach asynchronously, while just over 39% of respondents who had taught more than 10 sections before Covid taught asynchronously. Slightly more than 51% of respondents with 1-10 sections of previous online experience taught both asynchronously and synchronously (compared to about 48% of respondents who had taught more than 10 sections prior to Covid), and just under 18% of respondents with 1-10 sections of previous experience taught synchronously (compared to 13% of those who had taught more than 10 sections prior to Covid) .

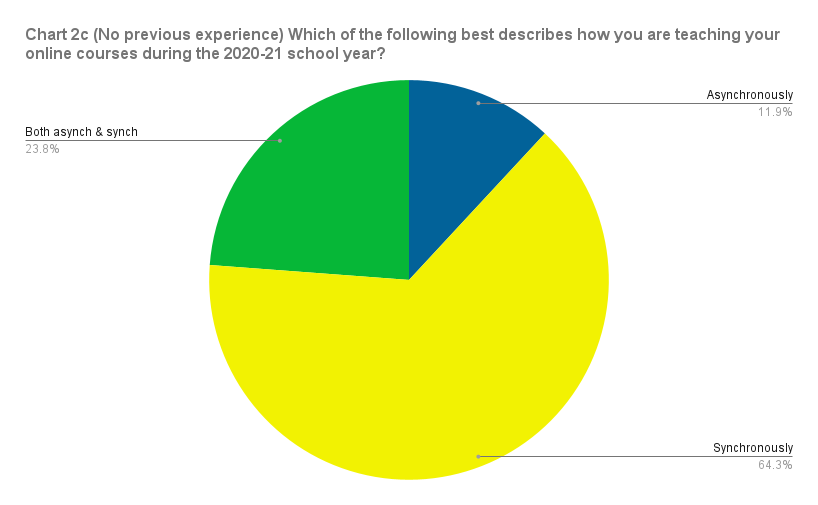

In contrast, Chart 2c shows the answers from those survey participants with no prior to Covid-19 experience teaching online. Twenty-seven respondents who had no previous experience teaching online--just over 64% of this group—said they taught their online classes synchronously, while just under 24% said they taught both synchronously and asynchronously, and just under 12% indicated they taught asynchronously.

The next question on the survey asked participants why they were teaching synchronously or asynchronously. The answer options were:

- My institution is requiring that all courses originally scheduled to be face to face to now be taught synchronously (or asynchronously)

- My department or program is requiring all courses originally scheduled to be face to face to now be taught synchronously (or asynchronously)

- After speaking with other instructors in my department or program, I decided to teach online synchronously (or asynchronously)

- After speaking with students in the program or the course, I decided to teach online synchronously (or asynchronously)

- After speaking with students in the program or the course, I decided to teach online synchronously (or asynchronously)

- I decided on my own to teach my online courses synchronously (or asynchronously)

- Other

It is worth noting that I made an error in constructing these questions. Those who indicated in an earlier question that they were teaching synchronously or both synch and asynch were directed to a version of the question where they could select only one option, while those who were teaching only asynchronously were directed to a similar question but one that allowed respondents to select all options that apply.

The majority of respondents—a bit over 38%—indicated that they decided on their own to teach online synchronously, asynchronously, or both, and about 26% of respondents indicated they were required to teach online in a particular mode (typically synchronously) by their institution, department, or program. Over 20% of respondents selected "Other" and added a more specific response. Some of those "Other" answers explain why the survey respondent made the choice they made (which is to say they too had a choice), some explain ways in which they didn't have a choice but to teach online in a particular mode, and some address other issues.

The follow-up interviews I have conducted to date suggest that the answer to both of these questions are in many ways more complicated than I anticipated.

Several interviewees mentioned that their institution had many gradients for teaching formats, ranging from completely online and asynchronous to completely f2f and synchronous. Some interviewees also mentioned that they essentially switched modes during the course of the school year, often after they completed the survey. So while I was intending to neatly divide participants into either the categories of synchronous or asynchronous, the division between these categories for many participants was more complex than the answers here might suggest.

Second, some interviewees said they varied or changed their approach based on the specific context: that is, some interviewees who answered on the survey that they taught all of their courses synchronously included some asynchronous class activities and assignments, and vice-versa. Some faculty taught some of their courses synchronously and others asynchronously, and this was a more common approach for those who had previous online teaching experience. In the interviews I've conducted to date, the most common explanation for teaching "both" had to do with the level of the class: typically, faculty were more likely to teach advanced classes synchronously. That said, I think it is telling that a clear majority of participants who had no experience teaching online prior to Covid elected to teach synchronously while survey participants who indicated any previous experience teaching online were much less likely to teach synchronously.

I was also surprised that a majority of respondents—while essentially required to teach online by their institutions—were able to make their own choices about teaching online synchronously or asynchronously. Again, the interviews have filled in a lot of the details regarding the survey answers. On the one hand, it's clear that a lot of faculty participating in this survey were not "required" but were "strongly encouraged" by their institutions to teach online synchronously. This was most often the case at institutions which, prior to Covid, did not teach many courses online and where the student population is almost exclusively traditional students—that is 18-22 years old, full-time students living on or near campus. On the other hand, several interviewees said that they too were surprised at how flexible their administrators were in allowing faculty to teach online in the mode that they think made the most sense for their courses and teaching. Though it is also apparent from the interviews that many university administrators became less willing to allow faculty teaching mode requests after the 2020-21 school year.

Impressions from the Likert scale questions

The survey concluded with a series of Likert scale questions that asked respondents the extent to which they agreed with specific statements regarding online education. Taken as a whole, the majority of respondents indicated that they had mostly favorable impressions of online teaching. However, there are some differences between those respondents with no previous experience teaching online and those who had taught online prior to Covid.

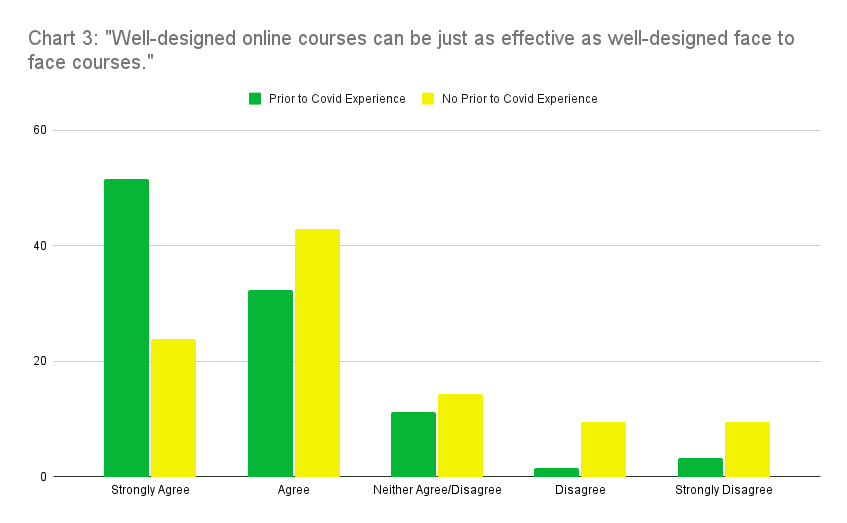

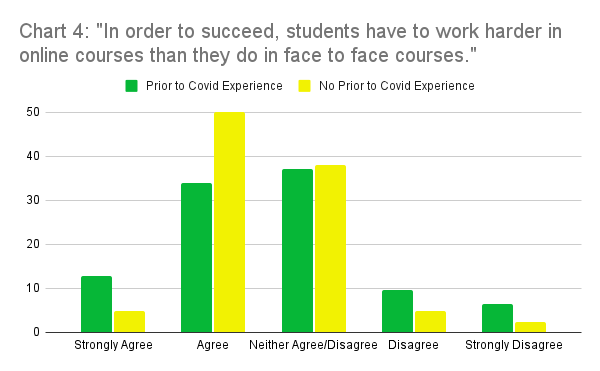

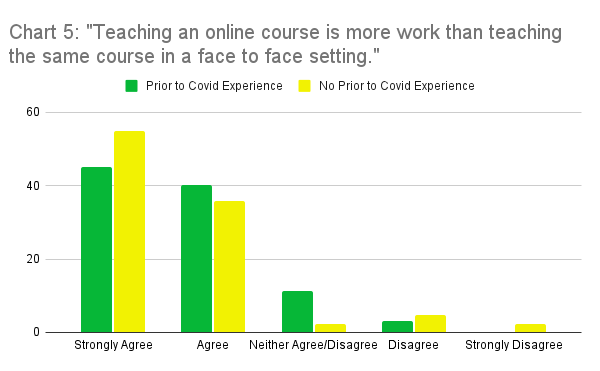

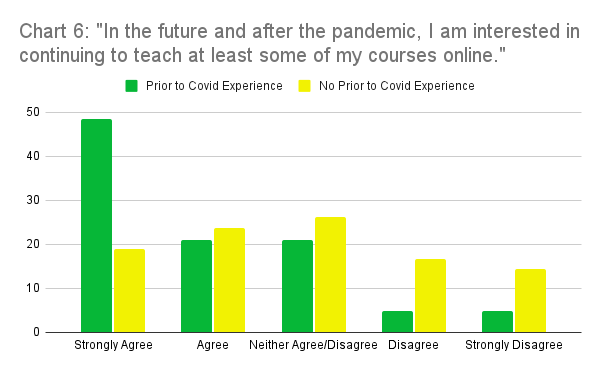

Charts 3, 4, 5, and 6 compare the responses to the Likert scale questions of respondents with Prior to Covid experience teaching online with those who had no experience teaching online prior to Covid. These charts represent the percentage of respondents in each category and not the actual number of responses.

Chart 3 depicts the responses to the question "Well-designed online courses can be just as effective as well-designed face-to face-courses." On the whole, about 77% of respondents regardless of past experiences strongly agreed or agreed with this statement. Based entirely on my own impressions and experiences of defending the validity of online courses in the past (not to mention the skepticism expressed by folks like Zimmerman), I believe that high level of agreement to this question suggests an increasing level of acceptability of online courses from college faculty—even those who, prior to Covid, had no experience teaching online. At the same time, I think this comparison makes clear that those who did not have online teaching experience prior to Covid remain more skeptical of the format. The number of respondents who disagreed or strongly disagreed is small, but clearly higher among those without previous experience.

Chart 4 depicts the responses to the question "In order to succeed, students have to work harder in online courses than they do in face to face courses," and Chart 5 depicts the responses to the question "Teaching an online course is more work than teaching the same course in a face to face setting." The answers to these two questions suggest a higher level of agreement regardless of prior to Covid experience teaching online.

Chart 6 depicts the answer to the question "In the future and after the pandemic, I am interested in continuing to teach at least some of my courses online." Clearly, survey respondents who had prior to Covid experience teaching online are more enthusiastic about teaching online in the future. This isn't surprising, but the responses from survey participants with no prior to Covid online teaching experience is more muddled. Just under half of those with no prior to Covid online teaching experience either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement about wanting to teach online in the future. That suggests to me that many of these respondents perhaps have changed their minds about the validity of online teaching based on their experiences of online teaching during Covid. At the same time, just over half of the respondents who had no prior to Covid online teaching experience are either ambivalent or uninterested in continuing to teach online after the pandemic.