Print to Screen

The six salient composing decisions that describe the participants’ multimodal composition processes define their assembling of multimodal ensembles. Three of these salient decisions are quite familiar to writers of print texts, though they have been widely sidestepped in the literature on digital text production. When I first began this study, I did not expect to find participants’ salient composing decisions to be defined by traditional print-based decisions. After all, most often writing decisions that were recognized in the research of print text had mainly been devalued for their bases on cognitive theories of writing. Scholars instead focused on the changes of the nature of texts from alphabetic to multimodal content and the challenges posed by the variation in medium. Nonetheless, in this study, I adopted three previously coined terminologies found when describing decisions of writers of print texts. Specifically, I adopted three composing activities described in Flower and Hayes’ (1981) cognitive writing model: planning, translating, and reviewing. In this section I discuss how I extended these three writing decisions to describe participants’ multimodal composition processes.

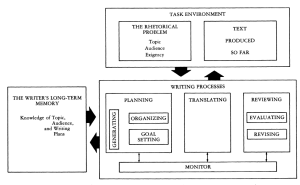

An overview of Flower and Haye’s (1981) cognitive model of the writing process can be seen in the juxtaposed figure. In their model, Flower and Hayes (1981) describe the three main activities employed by writers as planning, translating, and reviewing, all of which have both an input and an output relationship with the writer’s long-term memory and task environment. This process model of writing describes writers as cognitively planning their texts by generating ideas, organizing ideas, and setting goals. As I discuss in the proceeding section, planning is detached from the working environment. The second main writing activity is translating, which considers the technical reworking of content. Unlike planning and reviewing, this activity is noticeably simple and without any subcategories. The findings of this study will elaborate on translating as a multimodal activity and give this task the fuller description it deserves. The final category, reviewing is defined by evaluation and revision of the text. This activity was also a salient composing decision in this study’s findings and, as in the Flower and Hayes (1981) model, this activity is used to identify the iterative nature of composition. All three of the salient composing decisions play a role in the study’s findings and are understood as multimodal activities used to describe the production of digital texts. The discussion that follows elaborates on these decisions and relates them to the overall redesigning efforts that guided the process as a whole.

An overview of Flower and Haye’s (1981) cognitive model of the writing process can be seen in the juxtaposed figure. In their model, Flower and Hayes (1981) describe the three main activities employed by writers as planning, translating, and reviewing, all of which have both an input and an output relationship with the writer’s long-term memory and task environment. This process model of writing describes writers as cognitively planning their texts by generating ideas, organizing ideas, and setting goals. As I discuss in the proceeding section, planning is detached from the working environment. The second main writing activity is translating, which considers the technical reworking of content. Unlike planning and reviewing, this activity is noticeably simple and without any subcategories. The findings of this study will elaborate on translating as a multimodal activity and give this task the fuller description it deserves. The final category, reviewing is defined by evaluation and revision of the text. This activity was also a salient composing decision in this study’s findings and, as in the Flower and Hayes (1981) model, this activity is used to identify the iterative nature of composition. All three of the salient composing decisions play a role in the study’s findings and are understood as multimodal activities used to describe the production of digital texts. The discussion that follows elaborates on these decisions and relates them to the overall redesigning efforts that guided the process as a whole.

Decision 1: Planning

For Flower and Hayes (1981), writers compose their texts not just in the physical sense of transcribing words on paper, but also in cognitively conceptual ways. These researchers discovered that for writers to plan the text, they would conceive of the writing problem that they wished to address and its respective solutions. Using a metaphor commonly employed by Hayes (1989) to explain the nature of problem solving, a writing problem is a river that the writer needed to cross. Cognitively conceiving of a problem is the writer’s way of representing the problem. Planning decisions by the writer required representing the problem and conceiving of solutions, i.e. tasks and goals. I found that participants in this study similarly planned their texts by representing their composing problems. Planning indeed was a salient composing decision for participants and they, too, similarly identified goals and organized content as a way of representing the problem.

I was surprised to find planning to be such a salient composing activity, since such an activity was prominently identified for mainly print texts, and little was discussed in the literature examining decisions pertaining to composing digital texts. On the whole, such literature relegated planning decisions to pre-production activities, such as writing scripts and preparing storyboards, activities which are similar to the linear format of print texts, where content is more structured. Such storyboards consisted of organizing ideas by ordering scenes (such as scenes in a film) that detail major events, characters, and other characteristics of the text’s “plot.” Such an activity serves as an indication of Flower and Hayes’ (1981) emphasis on writers planning their texts by organizing their ideas ahead of transcribing their texts.

In this study, planning was a salient composing decision for participants as they produced digital texts and played a prominent role in guiding them as they set goals and organized content. Indeed, planning is a term that well described how participants in this study composed their texts: “to set goals and to establish a writing plan to guide the production of a text that will meet those goals” (Flower and Hayes, 1980, p. 12). What is unique to planning as a salient composing decision in this study, compared with Flower and Hayes (1980), is that these decisions—along with their cognitive conceptualization—also occurred in the participants’ immediate physical and digital environments. In other words, planning occurred not just as a separate prequel to the participants’ text production efforts, but also during the act of production. This meant that participants planned their texts with the very material they used to produce their texts. This extends Flower and Hayes’ (1980) view that planning occurs as an activity prior to the writer’s effort of working with the material of the text. Instead, in this study, I found participants also planning their texts with the material with which they produced the texts. In other words, they did not outline or brainstorm their texts in software different than the one they used to compose their digital multimodal texts. They also did not plan their texts by outlining its contents and organization on paper, for example. The reason why this may have occurred may simply be a methodological distinction, in that Flower and Hayes (1980) focused their findings on transcripts of writers talking out loud their thoughts while composing their texts. Although I also incorporated analysis of such transcripts, this study’s data included direct video observations of writers planning during the act of producing texts. This distinction afforded me the opportunity to base my analysis of writers’ salient composing decisions both on what they said and on what they did.

Furthermore, I found that planning helped participants to redesign educational contexts from available meaning-making material. So, while planning (i.e., setting goals and organizing content) participants simultaneously sought available resources with which to assist them to design multimodal ensembles. An example of this is WW’s mention of the PowerPoint presentations he had previously used in his face-to-face classes and a private collection of photographs that he had taken on nature trips. In this situation, WW used his PowerPoint presentations as a resource—i.e., an available meaning-making resource with which to plan his new text. When WW wanted to design his digital multimodal text, he used the available meaning-making resources to represent the problem to be solved. This illustrates how planning, for participants in this study, meant considering the available resources as a way of setting goals and organizing content in order to plan their texts.

1.1 Setting Goals

Participants gave themselves goals throughout the process, both in terms of the procedural/how-to variables and the content-to-be-presented variables for their audiences. So, participants would describe the purpose of specific content and also identify the appropriate actions needed to realize the purpose of the content. For example, BB states, “I’ve got real data, so I need to insert that, and I have to remember where to put it. I think it’s, so, this is real data from our own groups, and I wanna talk to the students about what real data looks like.” In this example, BB describes both the action that needed to take place and the purpose intended for the content in terms of her audience. This goal-setting activity thus helped her plan the development of her content and the overall production of the digital text. In general, setting goals was an activity integral to the meaning-making practices of participants.

1.2 Organizing Content

Organizing included arranging the order in which whole multimodal ensembles were to be presented in the participant’s text and also arranging the order of individual images and words within ensembles. For example, JJ spent time planning her text by organizing the order in which she wanted to present a series of images: “I’ve got to get my sequence on my pictures as they pop up in the appropriate, in a useful order. So I’ve renamed all the jpgs and I’m stepping through, kind of thinking about how I might, how I might show them.” In this example, the participant organized content as part of her planning activities. Organizing content was a way for participants to plan their ideas and determine the content to be included in their texts during the meaning-making process.

Decision 2: Translating

Translating represents writing decisions pertaining to transforming the technical qualities of content from one form to another. Transformation of these qualities includes a variety of communication modes employed by participants. Words, for example, were added and deleted; sound content was shortened or modified in volume; and images were resized and recolored. This study uses the term translating to describe the salient effort by participants to transform multimodal content in terms of its technical qualities.

Although, “transforming” or “modifying” or other similar terms may seem to be a more immediate way of describing this salient multimodal composing activity, I specifically use the translation to connect it to the broader research on writing. Indeed, the term translating echoes Flower and Hayes (1981) who used the term to describe writers enacting their writing decisions on paper. Since they researched writers composing print texts, these writers dealt solely with the technical considerations of composing words. In such instances, writers were concerned about grammatical issues, for example spelling and word choice. Concerns with transformation of alphabetic content (i.e., that of words) represented writers’ activities with the technical considerations of that specific medium.

In continuation with that observation, this study represents Flowers and Hayes’ (1981) view of translating activities more cohesively since it is understood as a multimodal composing activity. After all, this study’s participants created educational contexts using words and other media to form multimodal ensembles. Such an observation more fully encapsulates Flower and Hayes’ (1981) view that writers face the challenge of transforming cognitive content physically into words on paper because these writers’ thoughts also consisted of “imagery or kinetic sensations” (p. 373) . For writers of my study, translating consisted of composing multimodal ensembles that, as with their cognitive processes, consisted of images, auditory, and verbal content. That is why the term translating more fully represents the technical considerations of participants’ multimodal content.

The use of the term “translating” makes sense in linking this research to prior research on writing as a process. This study’s understanding of participants’ composing decisions as redesigning contexts develops that of Flower and Hayes’ (1981) who viewed writing to be the enactment of activities occurring solely in the mind of the writer. In other words, for Flower and Hayes (1981), writing decisions were separate from the act of working with the technical considerations of the medium used to represent these decisions, even though a salient cognitive work made by writers consisted of solving the technical considerations of their content.

From the perspective of design, which I emphasize in this study, participants’ writing decisions are understood as decisions embedded in the very activities employed to compose texts. Recognition of available contexts that may be redesigned and formed into new contexts means literally reworking meaning-making material. So, while Flower and Hayes (1981) left translating as a salient cognitive composing activity by writers, this study views the enactment of writing activities as a part of the translating decisions. That indicates that when writers of digital texts move, resize, and edit words and the like in their texts, they are making decisions both cognitively and “physically” regarding the technical elements of the content. The reworking of the content’s technical elements on the screen is part of the thought and the thought is part of what occurs on the screen.

2.1 Translating Words

A salient element of the range of translating activities made by participants included modifying and editing words to create meaning. Participants revised words, added words, deleted words, and created spaces for these words. For example, participants talked about “wording” and, in turn, revised the wording in the text. Similarly, they added new words and deleted words to their texts. These activities also included creating spaces into which words could be added in the future as composing continued. The visual variable of adding words in several observations included software that required users to add “text boxes” into which words could be added. In such instances, the visual and the alphabetic content were interlinked. Such a connection between the verbal and visual elements of content was also seen as participants determined the size, style, and type of words to add to their texts. Translating words, namely, working with the technical considerations of words, was part of the overall redesigning efforts of the content.

2.2 Translating Audio

Because the production of digital texts included assembling multimodal ensembles that included spoken content, participants were observed working with the technical elements of such spoken content. For example, JJ spoke of how she would go about and “trim off some of the extra noise.” What this observation illustrated was that participants treated spoken content as malleable content. This allowed content to be omitted, revised, and shifted in the temporal geography of the text. Participants would pay attention to adding spoken content as they did with adding words and images. To record spoken content, then, meant that it was not just added on top of other modalities but that it was treated as content directly connected to other modalities. Translating audio was part of the assembling of multimodal ensembles that so defined participants’ digital texts.

2.3 Translating Images

Translating images meant working with the technical elements of visual content. This included making color-related choices and resizing and shifting images. For example, participants described how they used color as part of the design of the text: “my slides are not too fancy, just a white background” and “We’ll make it colored, something nice. Let’s make it pink.” In these circumstances, participants thought about color in similar technical ways as they did with words and audio—how these elements could be modified and edited to change meaning or to alter how they intended something to be understood by the audience. This included resizing images and treating words as images by changing their color and size. Oftentimes, the visual elements of words were treated as a technical visual consideration and therefore words were resized along with images. Along with translating words and audio, translating images was part of how participants created meaning and redesigned content to create new educational contexts in digital formats.

Decision 3: Reviewing

Another salient decision of participants’ multimodal composing process was the reviewing of content. Reviewing included participants backtracking and consciously returning to what they have composed so far. As with planning and translating composing decisions, reviewing is part of Flower and Hayes’ (1981) triadic model of the writing process. As defined by Flower and Hayes (1981), reviewing the production of the text is “a conscious process in which writers choose to read what they have written either as a springboard to further translating or with an eye to systematically evaluating and/or revising the text” (p. 374). Although their model focuses exclusively on writers who produce print texts, the defining characteristic of reviewing that applies in their study may also be adopted here. Namely, a salient characteristic of the composing process of writers of both print and digital texts is to pause and review their texts and their overall decisions in the construction of those texts. That this characteristic appears in both types of writers affirms that, in general, reviewing decisions are important to text production processes.

Reviewing decisions are telling in that they reveal that writers are constantly considering not just how to build the text, but also how to remake it. This further indicates that producers of digital texts are indeed redesigning educational contexts. Namely, the content is consciously being redesigned for its contextual features. Flower and Hayes (1980) argue that this pausing activity by writers indicates that they do indeed intend to create meaning. In other words, an indication of writers’ intention to create a purposeful text occurs “when writers test or evaluate what they just said to see if it is related to or consistent with other ideas” (p. 28). Reviewing activities indicate the remaking aspect of writers’ text production process, both as understood by Flower and Hayes (1980) and in this study.

This study furthers the claim made about the saliency of reviewing as an essential part of the composing process. It means that reviewing decisions by participants of this study indicates their intention to remake contexts. Writers of digital texts redesign their content with an awareness of its contextual considerations. The similarity to Flower and Hayes’ (1980) findings that advanced writers consider the contextual elements and constraints of their texts indicates that print and digital text production processes are indeed contextual activities. The making of context and its remaking guide writers as they create meaning. In this study, I mainly found that this process included participants’ considering the contextual elements of the content’s purpose, quality, and intended audience.

3.1 Review for Purpose

During the composing process, participants consciously reviewed their work by backtracking to what they had composed so far and examining content for possible revisions. For example, JJ said, “I need to go check it out and make sure it’s going to run,” when composing a database algorithm that she wanted to capture by video and embed in her own text. WW similarly stated how he needed to “go back and check” previously created content. Lastly, BB also spoke of the need to “go back through and make it flow.” Participants, then, consciously reviewed content in order to ensure that what they had incorporated into their multimodal texts was actually what they needed or intended to incorporate to create their desired meanings.

3.2 Review for Quality

Participants were also conscious about the quality of their texts as teaching materials. JJ, for example, while reviewing her work, said, “this, I guess, is a good illustration to the students of actual programming.” Quality of the text was then determined by the teachability of the text. In other words, participants frequently reviewed whether or not the texts produced the message they wanted to communicate as learning tools. For example, WW commented on the teachability of his texts in terms of how long he spent on a specific topic: “This is a long one. Probably way too long. Once again, my presentations have gone long.” After identifying the time spent addressing a specific issue in the text as too long, he makes a conscious decision not to revise the text with added introductory content, because that would extend the discussion even further. Participant WW, then, illustrated how he and others participants reviewed their texts in terms of the texts’ quality as teaching material. This unique aspect of reviewing decisions showed that the digital text productions discussed in this study pertains specifically to the educational aspects of multimodal composition process.

3.3 Review for Audience

Besides reviewing content for the sake of ensuring its purpose and quality, participants also commented on how readers might view the texts. This variable of reviewing included participants’ commenting on whether or not readers would find the content appealing. BB said, for example, “I have to get the raw stuff that I have into some sort of format that students won’t be bored out their mind to listen to.” This example illustrated how reviewing decisions were also linked to participants’ awareness of their audience. Reviewing decisions showed how the production of digital texts in this study was a way for educators to make meaning that addressed the needs of their specific students.

Redesigning Contexts

During my review of the literature I found that there is a broad agreement that writing practices have changed as communication becomes increasingly reliant on screen-enabled devices. Because of the broad spectrum of investigations into this topic, I expected differences from print-based composing practices but was not certain as to what composing decisions would ultimately be the salient features of participants’ multimodal composition processes. Also, because participants were experienced educators who were not part of a generation that grew up immersed in these technological changes and because of the educational aim of these texts, I was even less certain of what were to be the essential characteristics of contemporary composing decisions to be found in this study. What made the discovery of this study’s composing decisions more intriguing was the multimodal nature of the participants’ texts. After all, regardless of participants’ past experiences with technology and the texts’ intended purpose, all participants still needed to assemble multimodal ensembles. These were, after all, activities that defined the adoption of these new teaching practices.

As understood through the combined effort of the six salient composing decisions identified in this study, it may be said that participants redesigned contexts through a process that moved from available designs (i.e., available meaning-making resources that may be recontextualized) to designing. Such a process defines multiliteracy pedagogy (New London Group, 1996), which states that contemporary communication is an evolving event. The New London Group (1996) argues the following regarding contemporary education:

“literacy pedagogy must account for the burgeoning variety of text forms associated with information technologies. This includes understanding and competent control of representational forms that are becoming increasingly significant in the overall communication environment, such as visual images and their relationship to the written word—for instance, visual design in desktop publishing or the interface of visual and linguistic meaning in multimedia” (p. 61)

The research that stems from this argument represents a growing understanding that a world increasingly reliant on multimodal interfaces is changing our educational process inside and out. This includes changes to the way educators communicate with their students, as seen by this study’s participants. The argument of the New London Group (1996) is advanced by the findings of this study by helping better understand what it means for UE to produce texts in contemporary authoring environments. The three remaining salient composing decisions discussed in this section further explain what writers of digital texts do during the act of composing.

The salient composing decisions that emerge in this section help further articulate this understanding by describing how participants searched, selected, and repurposed as they redesigned contexts into new digital educational possibilities. Altogether, the salient decisions reflect a writing process guided by participants’ efforts to redesign contexts. The model is based both on the preceding discussion that articulated the three salient composing decisions identified by Flower and Hayes (1981) as multimodal activities and the proceeding discussion on the findings’ remaining salient composing decisions. The Flower and Hayes’s (1981) study is further incorporated into this new model by understanding the meaning-making roles of the text produced so far and the writer’s long-term memory as an available meaning resource. These resources are advanced by this section’s discussion of repurposing as a salient composing decision, whereby participants transfer both participants’ and non-participants’ previously created content into new digital contexts. The model developed in this section builds upon research on composing decisions that define both print and digital texts.

Decision 4: Searching

The salient composing decision of searching describes how writers of digital texts both locate and navigate through information. While the activity of locating information may be more evident when using the term searching, activities relating to the navigating process of opening menus and moving windows across the screen, for example, is less evident but as essential to describing this salient composing decision. Furthermore, searching in this study was not limited to locating and navigating in digital environments, but also included physical (non-computer related) events, such as looking up content in books. Because the basic premise of searching is the need to locate content that was already created, such activity also reflected the aspect of seeking meaning-making material during the redesigning process. The primary need for writers to seek out available meaning-making resources reflected the New London Group’s (1996) description of designing: “Designing always involves the transformation of Available Designs; it always involves making new use of old materials” (p. 74). Searching decisions described how participants sought out available designs (i.e., available meaning-making resources) during the process of creating new educational contexts.

Other researchers who investigate contemporary communication have also argued for the importance of learning how to search for content (e.g., Manovich, 2001), though their research focused on the influence of the internet on writers. Researchers who specifically focused on investigating writing activities as influenced by contemporary communication (e.g. Sirc, 2004 and Johnson-Eilola, 2004) also identified searching as a necessary factor for understanding composition in a landscape defined by new media. Still, their arguments mainly stem from influences of electronic networks that prompt users at large to search for content. Although in this study participants did search for meaning-making material online, their primary search activities were based on their need to incorporate multiple modes of communication. So, in contrast with researchers who emphasize searching as a salient composing activity in contemporary communication due to the influences of the internet, this study argues that searching was a salient composing activity because writers of digital texts need to draw on multiple modes of communication (i.e., sound, words, and images). So while this study does support searching as an essential activity for contemporary writers, it reached its conclusion due to a separate set of observations.

Another insightful aspect of searching as a salient composing decision is that the meaning-making process of producing digital texts relied on the capacity to both locate and navigate through content. Searching activity was an essential aspect of how writers of digital texts moved from Available Designs to Designing to a Redesigned product. This meaning-making process worked in part because of writers’ capacity to search for content. This finding argues in favor of writing researchers who emphasize the importance of teaching to search as a salient composing activity to students. For example, Sirc’s (2004) argument that teaching students searching strategies supports the demands of composing in a communication landscape influenced by new media. The emphasis on searching as a composing activity, as defined by this study, also better elaborated how searching activities included not just locating content but also navigating through content.

4.1 Locating Content

Participants were observed searching for content that they wanted to incorporate into their texts. I identified this early on in my interviews with participants. WW, for example, talked of being on “the lookout for things that might fit in to my classes.” Later on, during my direct observations, searching was more clearly noticed because it was an integral part of activities that define the composition process. For example, Participant WW was observed while he searched for content to include in his text, saying, “So I’m going to grab my book and I guess the best way of doing it is just as we have some of the other ones,” thinking aloud as he is also heard leafing through a book. This illustrated that whether it was in the immediate physical or digital environments, searching decisions required participants to locate content as part of the redesigning process.

4.2 Navigating through Content

Searching included both locating content and navigating through content. This included scrolling up and down windows, scrolling sideways in windows, minimizing and closing windows, opening menus, and moving a cursor up and down menu options. Although these activities seem technical in some sense, they are significant to composing practices because they illustrate that searching for content was not just about selection but about navigation. For example, JJ reached a point where she wanted to make the text accessible to students online. After spending several minutes scrolling up and down menus, up and down windows, she selected files to upload from her computer to her online teaching environment: “[I am] tired of scrolling down to try to find that stuff.” At this moment, JJ already spent several minutes clicking on menu items. All of these maneuverings were similarly observed in how other participants searched for content. Whether it was through menus or windows, content located on participants’ computers or on the web, searching for content requires participant to navigate through content. Altogether, locating and navigating content were part of how participants went from redesigning available meaning-making resources into new educational contexts.

Decision 5: Selecting

I expected to find participants enacting selecting decisions as part of their multimodal composition processes. Of the various views on selecting as a salient composing activity for contemporary writers, the most important one to this research was the understanding that such writers are constantly faced with making selections from an array of possible operative behaviors and modifiable content. The reason why other views on selecting may not have been identified as a salient composing activity, such as writers selecting options from an array of networked information, may be that participants showed limited usage of online meaning-making resources. The lack of interest by participants in incorporating online content where information is highly networked possibly limited such networked view of selection.

What is important about selecting as a salient composing activity in this study is that it emphasizes the writers’ capacity to remake content, which, in turn, highlights the redesigning aspect of producing digital texts. Selecting as a salient composing decision suggests that participants constantly faced an array of options and so were prompted to consider the varying possibilities of their meaning-making material. This emphasized the overall framework of their processes, i.e., the redesigning contexts model of multimodal composition. As observed in this study, selecting, then, was a defining characteristic of the production of digital texts by prompting participants to consider new ways of designing contexts.

5.1 Selecting Tasks

Participants had to select tools from menus and toolbars. Throughout the composing process, participants had to constantly choose tools for the task at hand from an array of possible tools. These types of decisions meant that participants needed to be aware of what task(s) they wanted to perform and what tool(s) to use from those available. For example, BB decided to view the arrangement of her slides while using PowerPoint, so she needed a specific tool that would allow her to view all her slides on a single screen. BB was then observed to move to the drop down menus at the top of the screen and to open up the menus until she located and selected her tool of choice. Similarly, other participants were observed selecting a tool or a functionality that were presented as a series of selections. These activities illustrated the importance of purposefulness when communicating information in multimedia-authoring environments.

5.2 Selecting Content

Participants selected words, audio, and images from an array of immediately available content. BB, for example, said he had “Already decided that I’m gonna turn this into two slides, so this guy here” and, at that moment, BB selected content on the screen and restated her intention to select content, “So, we want this part from the previous slide.” BB then moved content to a newly created section of her text, which represents a repurposing activity that’s discussed in the next sub-section. This illustrated how participants in this study were faced with making selection decisions pertaining to content throughout their production processes. Furthermore, it showed that selecting decisions were integral to the redesigning process as a whole by identifying how content had to be selected out of an array of possible content, showing that participants determined which content played a role in assembling multimodal ensembles.

Decision 6: Repurposing

Repurposing meant including content that was previously created by the participant or others with the purpose of being incorporated into the text. Repurposing reflects the “cutting-and-pasting” phenomenon of new media. It emphasizes active reconstruction pertaining to participants’ content composing decisions. This contrasts with the general theme of redesigning contexts that emphasizes the general formation of participants’ digital texts. In other words, repurposing describes the formation of the text’s individual content elements while redesigning emphasizes the general configuration of the text’s content as a whole for a new context. In other words, what is important about repurposing in this study is that it emphasized taking a previously created meaning-making material to create a new message, e.g., taking a print handout and making an image out of it so that it is embedded in a digital text. Another example would be using PowerPoint slides that were used for a face-to-face class presentation and embedding them as content in a digital text. As seen in these examples, embedding previously created content is a defining feature of the participants’ repurposing practices.

That repurposing practices are salient composing decisions in participants’ multimodal composing process has been previously identified in the literature. Heba’s (1997) argument for the rhetoricization of multimedia communication, describes the capacity for digital media to be repurposed as new content:

“in a multimedia database, a picture of a dinosaur that appears under the category of Plants and Animals can be reused as part of a visual collage in a multimedia timeline showing images of flora and fauna from the Mesozoic Age. An image of a tattoo on the Web turns up in a student’s POWERPOINT presentation on the cultural significance of tattoos. This ability to repurpose information across media and contexts allows for a “cut and paste” style of composition that, like a collage, creates meaning by assembling bits and pieces of previously constructed discourse and arranging them in new contexts and combinations. (p. 33)”

Heba (1997) describes practices that were so often observed during this study. Content was used and moved around a digital text or from a book, a web article, an audio recording, or a hard-copy version of a handout and embedded within a digital text to serve as new content. This is significant because it shows a relationship between repurposing as a salient composing activity and the redesigning contexts model of multimodal composition that emerged from this study. Heba (1997) similarly argues for extending the possibilities of the capacity of digital information. In this study, repurposing did not depend on content originally existing as digital media, as in the above example by Heba where content exists in a multimedia database, but also saw those possibilities by repurposing print meaning-making material. In other words, in this study, writers were also observed repurposing print material, such as content from print textbooks. What is important about repurposing as understood in this study is that it required the material to be previously created and to be embedded (and possibly manipulated) as new content into the digital text.

When describing the multimodal composing process of participants as a whole I employ the term redesigning contexts. Both this term and repurposing imply iteration. These aspects of participants’ decision-making as a whole are emphasized not just by the multiple occurrences of each decision but also because of the insight offered in the saliency of repurposing composing decisions. More than the other salient composing decisions, repurposing emphasized the awareness of an originating context. In a way, content that is repurposed required participants to recognize that there are other contents for what they repurposed. When a participant repurposed content from a PowerPoint presentation originally used in a face-to-face teaching scenario, she or he attested to its originating context. The insight of repurposing to the overall multimodal composition process of experienced educators is that in redesigning contexts, educators also needed to assess the possibilities and limitations of available meaning-making resources.

6.1 Repurposing Non-Participant Created Content

Participants used content other than their own to create their multimodal texts. In other words, participants repurposed content that was already available on websites and in books and either embedded that content into their texts in their original forms or edited the repurposed content from the original form. For example, at one point in composing a text, Participant WW said, “I’m going to grab my book from the Forest Service,” and then began typing notes into his text. WW, later on in the production process, actually embedded short video clips from a television show into his text. Similarly, BB and JJ also repurposed content that was not their own into their texts. The saliency of these activities indicated that producing digital texts required writers to consider available meaning-making resources to assemble multimodal ensembles.

6.2 Repurposing Participant Created Content

A second form of repurposing practices occurred with material participants had already created that was then repurposed for their multimodal texts. An example of this was JJ’s use of an image that she created specifically to be printed on paper to be handed out in class. JJ located an image file that she previously created for her courses, an abstract graphical representation of a concept she taught for one of her face-to-face lectures. She searched for the file and, using a screen capturing software, selected a portion of that original image which, in turn, became a new image file that would be used in her digital multimodal text. What happens in this instance illustrates how an educator repurposed teaching material for her multimodal text even though the material was originally produced for a paper handout. Furthermore, the writer recognized the malleability of the meaning-making material in multimedia-authoring environments and therefore repurposed only a portion of the original image. The saliency of participants’ repurposing practices, both of material created by participants and non-participants, indicated that their composition process required them to pay attention to available meaning-making resources in order to produce digital texts. When JJ repurposed her own content, she determined that only part of her print handout was to be repurposed. This advances this section’s discussion that participants went beyond repurposing content from one context to another but rather created new educational contexts, namely assembled content as new teaching possibilities with its own advantages and practicalities.

Results by Bluetortugas3, unless otherwise expressly stated, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.