Products of Design

The multitude of products created by the DMA campers encompass those both planned and unplanned by the teachers. We had planned for a few projects—image manipulations in GIMP, short movies created using their tablets and iMovie, and larger group projects. The less expected products include the hundreds of Photobooth pictures and extra iMovies created by girls who used the free time to work on new projects. As far as products were concerned, we learned quickly that our expectations rarely aligned with the actual outcomes we saw at camp, but these deviations, particularly in GIMP, allowed for us to foster design dispositions in different and unexpected ways—namely through allowing girls to play with programs and create products that were not only unexpected but also completely off the prompt. Additionally, design dispositions were encouraged through a re-engagement with the program in the second week of camp where the girls had an opportunity to return to the program with more digital experience under their belts, creating a second group of products that let us look at how their design tendencies shifted over the course of the camp.

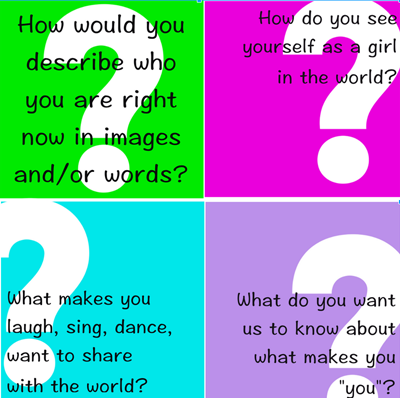

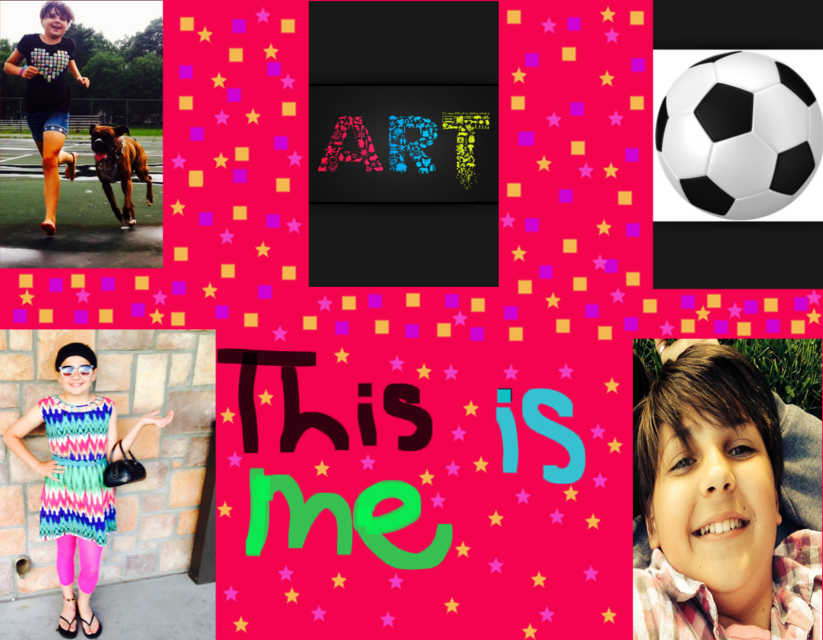

These are the questions we asked our campers to answer as they designed their first project for camp, a digital manipulation. We anticipated that we would receive projects that included a plethora of selfies, pictures of things they liked, and maybe a passing reference to camp here or there. The projects we received were wildly varied, many drastically unlike what we expected. When we designed their own projects in the weeks leading up to camp, we all focused on ourselves—images of ourselves, of our friends and families, of our likes and dislikes, and (sometimes) of our pets. We had organizing principles, a variety of color schemes, and text that helped ground our point. While we didn't think that's exactly what we would be getting from our rising sixth grade girls, we didn't expect quite the range we received, especially as our projects ended up being so similar to one another's.

The projects that the other girls designed were a diverse assortment. Some of the projects were fairly in line with our expectations—Emily and Morgan both created images that featured several pictures and examples of their personalities to describe themselves. Others featured one or two design elements—pictures, text, drawing—that were layered on top of another picture that they used as the background. Others, however, were completely unexpected: a picture of a fountain with "kool-aid water" (water that had been changed to encompass a plethora of rainbow hues) and pictures of friends but not of the creator. We were fairly perplexed, especially about the last few projects. We didn't see how these connected to the prompt or even the girls' interests as they had articulated them thus far. But we let the girls go through the design process on their own, trying to answer questions rather than direct them toward particular design choices.

One reason such a diverse group of projects was created was our decision not to share our own designs with the girls. We thought offering up our own projects as models would make them more likely to work toward the designs represented by those models than determining what they wanted to create. We chose to err on the side of design, or play, rather than on accuracy. As we watched the girls creating such different interpretations of the prompt, we realized how important our own stances toward design were for the camp: encouraging individual design as a goal in and of itself, rather than designs that met our expectations. Purdy (2014) argued that design thinking "emphasizes the importance of considering many different responses to a design task, of not getting locked into one response too early to the exclusion of other options" (p. 629). The goal was not for the girls to create products that looked like ours but ones that reflected their own design sensibilities. In our attempt to instill design dispositions in these girls, we had to let go and allow for the girls to create their own products, even as we looked in with confusion as to why they wanted to focus their "I Am" projects on other girls or even particular objects that seemed completely unrelated to them. They weren't fulfilling our expectations, but that's part of crafting a disposition geared toward encouraging design rather than just learning the basics of a particular tool. If we were encouraging design dispositions, we were also encouraging multiple solutions or multiple designs for any given prompt or problem.

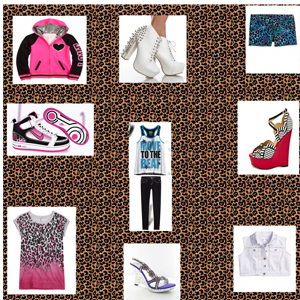

The focus on GIMP dropped out in the second week of camp. Only one girl, Madison, chose to purposefully re-engage with the program, but two small groups of girls ended up using GIMP to create manipulations for their final projects. One group, having finished their final product with a full day left to spare, decided to use GIMP to create personal 'style boards' to go along with the project. The process of working with GIMP this time looked exceptionally different than it did the first week. After one or two questions about getting started, the girls quietly started designing their style boards. They proved capable on their own, and two of the girls created much more detailed, complicated works than they did for their "I Am" projects. The two periods of interaction with GIMP could not have been more different. During "I Am," we were constantly moving around the room, having to keep lists in their heads of who needed help next as they tried (and failed) to use some sort of zone defense to keep up with answering questions and helping girls work with the difficult program. This time, Megan hung back on her own computer next to her group of four girls, working on her own style board, getting up to answer a quick question from time to time, questions that more often had to do with what she thought of a particular background or shoe choice than the actual, functional use of the tools. In Selber's (2004) terms, the girls were no longer acting as users, working through functional literacy, but were instead acting as producers of digital media, using rhetorical literacy.

We can see here, again, the cycle of engagement acted out. By thinking about this cycle over the long course of an entire week of camp (from Tuesday of Week 1, learning GIMP, to Wednesday of Week 2, taking on the extra GIMP project), the girls exhibit very different dispositions toward the program. During week one, they were frustrated and beaten down by the project, but their time disengaging and learning about other digital media platforms—iMovie and the green screen—allowed for them to come back to GIMP more curious, interested, and re-engaged. This re-engagement with a difficult program allowed for the girls to try again on something that seemed very defeating the first time around. For campers like Morgan and Alicia, this was not necessarily as critical since they had few problems during the original engaged phase with GIMP, but for Lily and Eliana, re-engaging with GIMP allowed for them both to try again on a platform that they found very difficult. Instead of the awkwardly cut out images and odd layout of the first project, these designs featured more pictures, more interesting layouts, and more overall design choices made. Re-engaging positively influenced their design abilities and number and type of choices. The projects were not necessarily "better" designed (based on our personal senses of design and style), but the girls utilized more tools and made more choices, leading to more multimodal design being used in these projects than the originals. We believe that by re-engaging with GIMP, girls were able to leave camp with additional, positive experiences with the program, further encouraging design dispositions.

What Is DMA? And Why Does It Matter?

We offer here a brief overview of the camp and our goals for it. In brief, we wanted DMA to provide girls an opportunity to create—rather than merely consume—digital texts. Twenty rising sixth grade girls participated, from two historically low-performing elementary schools in lower-income neighborhoods in Louisville. Using tablets, desktop computers, and digital cameras, girls learned, used, and played with image manipulation and video editing. We selected technologies that would give girls the opportunity to develop their projective identities, to imagine a technological place for themselves both within their projects and in their futures. We chose two focal technologies: the Mac-standard video-creation software iMovie and the free Photoshop-like image manipulation program GIMP. Since Sheridan and Rowsell (2010) identify strong support for social sharing as key to building architectures of participation for digital media literacy (pp. 46-7), we also asked girls to leave daily comments on the camp blog and share photos with one another on Instagram. Then, during the second week of DMA, girls designed group projects that proposed solutions to problems in relation to the camp's theme, Designing Your Future, and presented their projects to an audience of family, teachers, and university community members.

The primary exigency for DMA was the worsening underrepresentation of women in technology-related fields—and the particular risks for girls from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. A U.S. Department of Commerce study found that in 2009 women held just 27% of science and math jobs, a drop of three percentage points since 2000. Many researchers suggest this gap is the result of adolescent girls' tendencies to underestimate their own abilities and to have higher anxiety in science and technology (Andre, Whigham, Henrdickson, and Chambers, 1997; Britner and Parajes, 2005). Peggy Orenstein (1994) called this the "confidence gap," and her research has suggested that this anxiety and underestimation often begins in middle school. Furthermore, adolescents in low-income schools are also affected by what Henry Jenkins (2009) called "the participation gap"—they are much less likely than peers at wealthier schools to use technology outside of highly restricted academic applications, and thus much less likely to see themselves as participants in digital environments. Jenkins argued that, in our current cultural moment, children have "unequal access to the opportunities, experiences, skills, and knowledge that will prepare [them] for full participation in the world of tomorrow" (p. xii). More equitable digital participation, he argued, is how children and adolescents come to understand interface gestalts and develop creative technological problem-solving skills. Thus, DMA aimed to offer girls going into lower-income middle schools a chance to build technological confidence at a critical age, right before they were asked to make one of their first significant decisions about their educational futures: which elective classes to take in middle school.

We wanted DMA to be a confidence-building experience for girls that offered them two sets of possibilities: one as active bodies on a university campus where they might envision themselves, and another as thoughtful producers of digital texts. To address the former, we chose the theme, Design Your Future, as a way for girls to think about how they might pursue degrees and careers using technology in whatever futures they plan for themselves, whether as a wedding designer, soccer player, or student in an advanced math class in middle school. To emphasize the latter, we borrowed from composition's disciplinary emphasis on text creation as well as reading and critical analysis (see Selber, 2004). As a discipline, we make text creation the center of classroom learning based on a foundational understanding that students learn to write by writing. By extension, many scholars in our field have taken up a similar stance that students learn to compose for a range of audiences and contexts by composing in forms including but not limited to print-based text.

From our initial survey and participant interviews with DMA participants, we discovered girls often associated technology use in school with testing, gaming, or, at most, text consumption rather than any active creativity or design thinking associated with text creation. When asked in interviews about technology use in schools, girls often referenced "computer class," where the main objective was to use computer programs to complement curricular learning (e.g., "Cool Math"), not to engage in media creation. Further, our initial survey results indicated that, while the majority of girls at DMA had watched videos online, only two reported making their own videos. Yet every participant indicated a desire to make videos during camp. It was this fuller participation in digital spaces that DMA sought to encourage.

To help girls imagine themselves as active producers and participants in digital spaces, we turned to the scholarship of Gee (2004) and Selber (2004) as theoretical frameworks. First, we used Gee's projective identities as the trajectory for how we hoped girls would participate in digital design. Gee (2004) characterized projective identities in two parts: as acts of projecting values and desires, and of seeing these projections as projects in the making (p. 112). The goal is for learners to see these acts "as their own project in the making—an identity they take on that entails a certain trajectory through time defined by their own values, desires, choices, and goals" (Gee, 2004, p. 114). For DMA, we hoped that girls would imagine future identities as capable, confident creators in and through digital projects. To trace these identities in the making, we used Selber's (2004) framework from Multiliteracies for a Digital Age. Based on Selber's categories, we developed three objectives for girls: to be users (functional literacy), questioners (critical literacy), and producers (rhetorical literacy) of digital media. We hoped that, through play and collaboration, girls would participate in Purdy's (2014) approaches to design thinking: not only in analysis but also in synthesis, designing their futures in and through digital texts that might "shape the future and motivate the ways in which we (learn to) represent and communicate" (p. 626).

References

Andre, T., Whigham, M., Hendrickson, A., & Chambers, S. (1997, March). Science and mathematics versus other school subject areas: Pupil attitudes versus parent attitudes. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching. Chicago: NARST. Retrieved from ERIC.

Auer, P. (1992). Introduction: John Gumperz' approach to contextualization. In P. Auer and A. Di Luzio (eds.), The contextualization of language. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins.

Bauer, J. (2000). A technology gender divide: Perceived skill and frustration levels among female preservice teachers. Annual Meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Association. Bowling Green, KY. 15 November 2000. Conference Paper.

Blair, K.L., & Tulley, C. (2007). Whose research is it anyway? The challenge of deploying feminist methodology in technological spaces. In H.A. McKee and D. N. DeVoss (eds.), Digital writing research: Technologies, methodologies, and ethical issues (pp. 303-17). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Blair, K.L., Fredlund, K., Hauman, K., Hurford, E., Kastner S., & Witte, A. (2011). Cyberfeminists at play: Lessons on literacy and activism from a girls' computer camp. Feminist Teacher, 22(1), 43-59.

Blair, K. L. (2012). A complicated geometry: Triangulating feminism, activism, and technological literacy. In L. Nickoson and M. P. Sheridan (eds.), Writing studies research in practice: Methods and methodologies (pp. 63-71). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Brandt, D. (1998). Sponsors of literacy. College Composition and Communication, 49(2), 165-85.

Britner, S., & Parajes, F. Sources of science self-efficacy beliefs of middle school students. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 43(5), 485-99.

Chandler, S., & Scenters-Zapico, J. (2012). New literacy narratives: Stories about reading and writing in a digital age. Computers and Composition, 29(3), 185-190.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.) (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London: Routledge.

Cushman, E., Getto, G., & Ghosh, G. (2012). Learning with communities in a praxis of new meida. In C. Wilkey and N. Mauriello (eds.), Texts of consequence: Composing social activism for the classroom and community (pp. 295-315). New York, NY: Hampton Press.

Denecker, C, & Tulley, C. (2014). Introduction. The Writing Instructor. Retrieved from http://www.writinginstructor.com/

Gee, J. P. (2000). New people in new worlds: Networks, the new capitalism and schools. In B. Cope and M. Kalantzis (eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp. 43-68). London: Routledge, 2000.

Gee, J.P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2014). How to do discourse analysis: A toolkit. (2nd ed). London: Routledge.

Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Graupner, M., Nickoson-Massey, L., & Blair, K. (2009). Remediating knowledge-making spaces in the graduate curriculum: Developing and sustaining multimodal research. Computers and Composition, 26(1), 13-23.

Halladay, M.A.K. & Hasan, R. (1989). Language, context, and text: Aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University.

Hull, G., & Nelson M. (2005). Locating the semiotic power of multimodality. Written Communication, 22(5), 224-61.

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Journet, D. (2007). Afterword. In C. L. Selfe (ed.), Multimodal composition: Resources for teachers (pp. 187-91). Creskill, NJ: Hampton.

Kling, K. C., Hyde, J. S., Showers, C. J., & Buswell, B. N. (1999). Gender differences in self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(4), 470-500.

Knievel, M, & Sheridan-Rabideau, M. P. (2009). Articulating 'Responsivity' in context: Re-making the MA in composition and rhetoric for the electronic age. Computers and Composition, 26(1), 24-37.

Kress, G. (1999). 'English' at the crossroads: Rethinking curricula of communication in the context of the turn to the visual. In G. E. Hawisher and C. L. Selfe (eds.), Passions, pedagogies, and 21st century technologies (pp. 66-88). Logan, UT and Urbana, IL: Utah State UP and NCTE.

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. New York, NY: Routledge.

Leverenz, C. (2014). Design thinking and the wicked problem of teaching writing. Computers and Composition, 33, 1-12.

Lindquist, J. (2012). Time to grow them: Practicing slow research in a fast field. JAC, 32(3&4), 645-66.

O'Brien, H. L., & Toms, E. G. (2008). What Is user engagement? A conceptual framework for defining user engagement with technology. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(6), 938-55.

Orenstein, P. (1995). Schoolgirls: Young women, self-esteem, and the confidence gap. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Powell, A. H. Access(ing), habits, attitudes, and engagements: Re-thinking access as practice. Computers & Composition, 24(1), 16-35.

Purdy, J. P. (2014). What can design thinking offer writing studies?. College Composition and Communication, 65(4), 612-641.

Rickly, R. (2007). Messy contexts: Research as a rhetorical situation." In H.A. McKee and D. N. DeVoss (eds.), Digital writing research: Technologies, methodologies, and ethical issues (pp. 377-97). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Ridolfo, J., Rife, M.C., Leon, K., Diehl, A. Grabill, J., Walls, D., & Pigg, S. (2011). Collaboration and graduate student professionalization in a digital humanities research center. In L. McGrath (ed), Collaborative approaches to the digital in English studies (pp. 113-57). Computers and Composition Digital Press. Retrieved from: http://ccdigitalpress.org/ebooks-and-projects/cad

Selber, S. (2004). Multiliteracies for a digital age. Urbana, IL: Conference on College Composition and Communication, National Council of Teachers of English.

Selfe, C. L. (1999). Technology and literacy in the twenty-first century: The importance of paying attention. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois Press.

Selfe, C.L., and Hawisher, G.E. (2007). Gaming lives in the twenty-first century: Literate connections. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sheridan, M.P., and Rowsell, J. (2010). Design literacies: Learning and innovation in the digital age. London: Routledge.

Vygotsky, L. (2012). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Yancey, K. B. (2004). Made not only in words: Composition in a new key. College Composition and Communication, 56(2) 297-328.

Yancey, K. B. (2009). Re-designing graduate education in composition and rhetoric: The use of remix as concept, material, and method. Computers & Composition, 26(1).