Game Pedagogy: What is the Game Factor?

The Game Factor is the term we use to describe the educational potential of games to teach student players complicated concepts and processes. When we began designing Peer Factor, we wanted to create a learning environment in which student players wanted to understand peer review based upon the feedback they received from the game. That is, we wanted students to begin questioning why they were doing well in the game (or poorly) and to begin to draw comparisons to their own peer review experiences. Gee (2003) called this the discovery principle of learning: “overt telling is kept to a well-thought-out minimum, allowing ample opportunity for the learner to experiment and make discoveries” (p. 138).

To increase the Game Factor in Peer Factor, we relied upon three hypotheses about games as learning tools: they are interactive, they are immersive, and they provide an immediate response to players’ actions.

Games are Interactive

Interactivity is a widely discussed topic among game designers and interactive media scholars. Basically, it refers to the ability of the software to respond to a player’s actions. According to Klimmt and Hartmann (2006), “Interactivity is the possibility of a continuous exchange between players and the game software. Each allowable action or input from the players is received and processed by the game software and contributes to change in the game system’s condition” (p. 137). In the same edited collection, Lieberman (2006) defined it as, “[taking] into account previous actions or messages generated by both the player and the game” (p. 381). Sellers (2006) defined a game as being interactive if it meets the following conditions: “presents state information to the user, enables the user to take actions indirectly related to that state, changes the state based on the user’s action, and displays that new state” (p. 13).

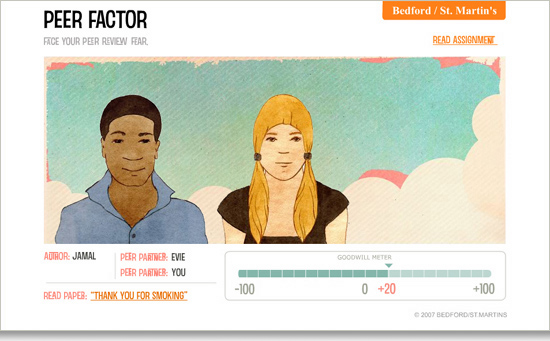

In designing Peer Factor, we wanted the game to respond immediately after a player selects a response. In this way, players would be able to see the results of their actions immediately. It was our goal to have them then begin to question what had made their selection successful or unsuccessful. A successful response, one that is represented by the best practices of peer review, results in three types of feedback (see Figure 1):

- Auditory: an imaginary audience reacts with hurrahs and shouts of approval with a successful response.

- Visual: the most obvious feedback mechanism, the Goodwill Meter, moves toward the positive.

- Gestural: the non-player character to whom the player is supposedly giving feedback smiles.

Figure 1: Screenshot showing the results of a +20 response for Episode One.

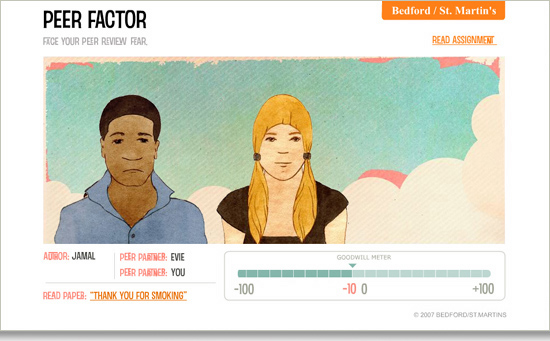

Similarly, a less than successful response is represented by the same three modalities (see Figure 2 below):

- Auditory: an imaginary audience reacts with sounds of disappointment.

- Visual: the most obvious feedback mechanism, the Goodwill Meter, moves toward the negative.

- Gestural: the non-player character to whom the player is supposedly giving feedback frowns and looks disappointed.

Figure 2: Screenshot showing the results of a -10 response for Episode One.

One of the great benefits of using game technology to teach complex processes like peer review is that players can become immersed in an environment that responds to their input and changes certain conditions of that environment based upon the player’s input. Gee (2003) referred to this as the transfer principle: “learners are given ample opportunity to practice, and support for, transferring what they have learned earlier to later problems” (p. 138). As players begin to hypothesize what went well for one question, they can apply that learning to future questions.

Games are Immersive

Another important element of the Game Factor is the immersivity a player experiences while playing a game. According to Brown and Cairns (2004), immersion refers to a player’s involvement with a game (p. 1300). They described immersion as having to do with engaging and maintaining a player’s attention (p. 1300). de Castell and Jensen (2004) similarly described immersivity as a game’s ability to capture and hold a player’s attention:

Within the environment of a computer game, the mobilization of players’ attention and intelligence through interactive game play can encompass the acquisition of motor and perceptual skills, the completion of increasingly complex interlinked tasks, the learning and systematic pursuit of game-based narrative structures, the internalization and enactment of appropriate affect, and a range of other attendant forms and conditions of learning. (p. 396)

Ermi and Mäyrä (2005) cited Pine and Gillmore in mapping immersion across two dimensions: participation and connection (see Figure 3). They described immersion along the following continuum:

Figure 3: a visual representation of Ermi and Mäyrä’s description of the dimensions of immersion in games (p. 18).

Still, with all of the research into the subject, immersion remains a highly idiosyncratic phenomenon. That is, what one person finds immersive, another might not. This is due to several factors: a player’s background experiences with games as well as the content and interface design of a particular game, a player’s familiarity with computer games in general, not to mention any number of cultural and environmental factors as well. For example, one of the authors, Ryan, doesn’t find Massively Multi-Player Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs) like World of Warcraft to be terribly immersive. Particularly due to the amount of time spent on resource management, the game does not sustain his disbelief. It feels too much like work to him. Salen and Zimmerman (2004) explained why this may be the case. They cited Gorfinkel, who argued that immersivity is “an experience that happens between a game and its player, and is not something intrinsic to the aesthetics of the game” (p. 452). Appropriately, then, Salen and Zimmerman described immersion as a kind of remediated play, one that is constituted by a type of double consciousness whereby the player is highly “aware of the artificiality of the play situation” (p. 451). So, as Ryan begins to manage his resources in World of Warcraft and it begins to become laborious, for him, at least, the artificiality of play has been replaced by work. This is not the case for everyone, however, and World of Warcraft remains an intensely popular game, one where many players are happy to spend many hours managing their resources and questing.

In designing Peer Factor, we were severely limited by budget constraints and time. Highly immersive games like MMORPGs are costly to build and maintain. At the time of this publication, a commercial game can take several teams of people (artists, writers, programmers, etc.) many months to produce, at a cost of several millions of dollars. As a consequence of not having these same resources, we chose to emphasize player choice as the main immersive element in the game. Players can choose from six different papers to peer review in Episode 1. In Episode 2, players are given the option of six different personality types to work with in soliciting reviews from the non-player characters (NPCs). They can also select from three different levels of drafts, from invention to a more developed and polished draft.

Another immersive element of the game is the Peer Fear Monster who appears randomly in the game and moves all about the screen. S/he makes a bouncing noise in Episode 1 and a cute, squeaky burble in Episode 2. If a player clicks on the Monster, he or she is treated to a peer review hint and a +10 point boost that will help him or her in the game. When we play tested the game, players looked for the Peer Fear Monster and tried to catch him, drawing them into the game.

Games have Immediacy

Immediacy is important to an educational game like Peer Factor because it is through the immediate feedback that players adjust their gameplay and begin to hypothesize why their goodwill meter is going up or down. On their next turn, players will experiment with their newly formed hypothesis, and see if it holds true. For example, if a player chooses a specific, generative comment and gets a good score, she is likely to try and find the most specific comment in the next round of play. If she chooses a generic, vague comment and her score goes down, she will likely choose better in the next round of play. After playing several rounds, we hope that players are better able to articulate what constitutes a good peer review comment.

In fact, in our play testing, we found that this held true. One student said that he learned how to identify high-scoring comments. Good comments, he noticed, were more specific and directed and bad comments were more general and "fuzzy."

We also designed Peer Factor with relatively few guidelines and hints in order to challenge all players to learn the game, thus learning the peer review process while playing. Garris, Ahlers, and Driskell (2002) argued that,

Feedback is a critical component of the judgment-behavior-feedback cycle. Individual judgments and behavior are regulated by comparisons of feedback to standards or goals. If feedback indicates that performance has constantly attained the goal, the game is deemed too easy and motivation declines. However, during initial game play, feedback typically indicates that current performance is below desired standards. (p. 454)

In other words, it is actually desirable in an educational game to see players failing at first. This means that they will adjust their in-game behaviors in line with the standards or goals set by the game. If most players can beat the game in the first round of play, there is very little incentive to continue the game. Gee (2003) called this the explicit information on-demand and just-in-time principle: “the learner is given explicit information both on-demand and just-in-time, when the learner needs it or just at the point where the information can best be understood and used in practice” (p. 138). Without immediacy, players are left wondering how their answers or responses would affect gameplay without immediate confirmation of the results of their actions.

Limitations to the Game Factor

The international computer game research consortium, the Learning Games Initiative, has a saying that all games teach. Gee, in his often cited book, What Video Games have to Teach us about Language and Literacy (2003), listed several dozen literacies that popular games encourage among their players. Yet, there are limitations to what educators can hope to teach with this medium, promising as it may be. Among these limitations is the fact that game designers cannot control the learning environment. We cannot determine, for example, how long or how well any individual player will play the game. We cannot control how well a player will play the game. And we cannot control exactly what a player will learn from the experience. We have designed the game to teach first-and second-year composition students the best practices of peer review; however, what players will take away from the experience relies largely upon the individual player, and upon the extent to which they are willing to immerse themselves in the environment and explore the various actions available to them.

By consciously designing a game rather than a tutorial—the difference being that the latter would tell players the correct answers and rely less on experimenting with better answers—we had to account for this lack of control to some extent, or else our secondary audience, instructors, might not adopt the game for use in their classes. What we did is to create a fairly comprehensive instructor’s manual that accompanies the game, providing sample learning situations and assignments for using the game as well as justifications for each possible answer in the game. We realized early on that the game would never work on its own without dedicated writing professionals who could explain the difference between a good answer and a better answer to their students. In fact, Zhu (1995) studied the effects of training on peer response groups and found that training student responders did significantly improve students’ ability to learn from the peer review process. Zhu concluded that “Teachers should help students acquire both the cognitive and cooperative skills needed for group work by providing instruction and feedback before and during cooperative activities” (p. 495). Zhu went on to state that, “given the importance of interaction and negotiation in peer response, a major part of the teacher’s duty when using peer response groups is to promote negotiation and interaction among students so that they can indeed enjoy the cognitive and social benefits of peer interaction” (p. 517). We would agree, and argue that our game should be only used in classrooms where it is a part of that training in negotiation and interaction, a part that is guided by instructors who make their expectations for the peer review process clear and accessible to the entire class.

We predict that even though games may become a more visible part of the writing classroom over the next several years, we will always need these writing professionals to help students apply what they learn from these games into real world practice.

Ryan M. “Rylish” Moeller

Ryan M. “Rylish” Moeller

Kim White

Kim White