Rhetoric and Reflection

In using reflection, one might start with the responsibility a student (or teacher) has as a citizen, which harkens back to our ancient Greek and Roman predecessors, including Isocrates and Cicero. Being civically responsible should include using rhetoric to reflect on and improve the society or community in which one thrives. The institute of higher learning is a perfect place for students to begin such reflection as their civic (and academic) responsibility.

This kind of reflection could be done within a framework of the rhetorical situation, allowing students to carefully read the educational context by learning to break a situation down into its formal elements in a manner similar to how Bitzer thought of it, and into its more dynamic elements per Biesecker. Practicing this strategy in the composition classroom would give students an approach to understanding communication in other contexts as well since any situation of human interaction can be read as rhetorical.

Bitzer defined the rhetorical situation as "a natural context of persons, events, objects, relations and an exigence which strongly invites utterance" (5). This context, to which he referred as the rhetorical situation, had three constituents: exigence, audience, and constraints.

Exigence

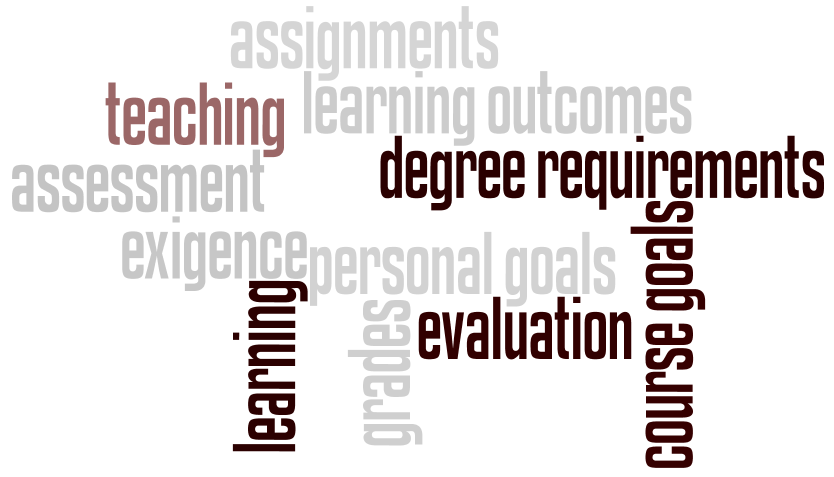

Exigence is described by Bitzer as "an imperfection marked by urgency; it is a defect, an obstacle, something waiting to be done, a thing which is other than it should be" (6). Exigence for students could include any obstacles to their learning, personal or academic; teaching and learning are "yet to be done"; transcripts, grades, degree requirements from students' perspectives are often "other than they should be."

Audience

Furthermore, rhetoric always has an audience, according to Bitzer "since rhetorical discourse produces change by influencing the decision and action of persons who function as mediators of change" (7). Students and teachers alike act as both rhetors and audience members with hopes of influencing the others in class, to learn, and to effect other positive changes.

Constraints

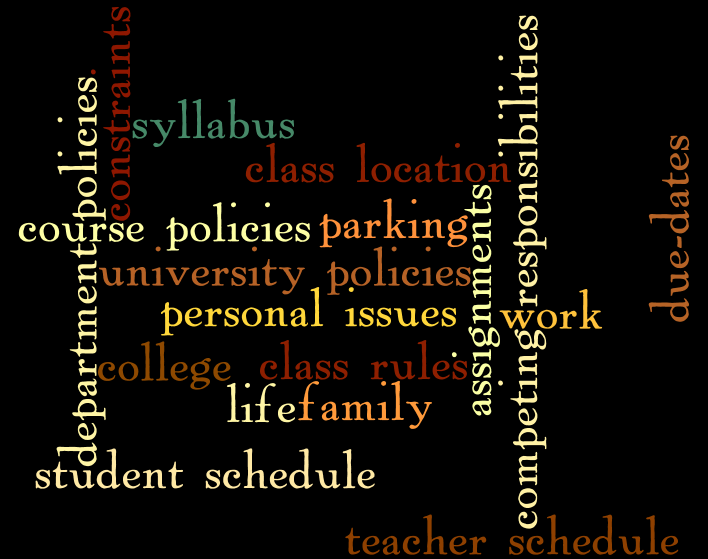

Finally, constraints, Bitzer explained, are "made up of persons, events, objects, and relations which are parts of the situation because they have the power to constrain decisions needed to modify exigence" (8). Students face a myriad of constraints when they enter and progress through college, such as timing, scheduling, reading/understanding the syllabus and assignments, locating classes, getting to the college, parking, meeting course objectives, and dealing with personal life issues that arise.

Biesecker criticized Bitzer's work heavily for seeing rhetoric as being determined by a set of stable elements in advance of the communicative action. Biesecker saw the rhetorical situation as being much more unstable than that. She explained that the subject-rhetor and audience member identities are not pre-existing to communication; rather, the rhetorical event "marks the provisional identities and construction of contingent relations that obtain between them" (126). Biesecker's work can be very enlightening for students in helping them see that people have the propensity to change through their communication with one another. This opens students up to the power of negotiation. The notion of dynamic identities can be an excellent tool for critical rhetorical reflection, as can analyzing the seemingly more stable elements of communication, which Bitzer's work points to, that affect students' learning environment.

Students can use this rhetorical framework to critically review and reflect upon their learning environment. They can look for the purpose of communication by finding out what potentially shapes the elements of exigence, audience, and constraints. They can become agents of change, engaging in critical rhetorical reflection, guiding and influencing the teaching and learning of their college experiences. Moreover, we educators can answer the call issued forth by O'Neill, Moore, and Huot to " … create a productive culture of assessment around the teaching of writing" (34) thereby showing students how to document and account for the learning that goes on in their composition classrooms. This active role we ask students to play allows them to develop agency in shaping their own education, and that of those who follow in their footsteps.

We live and work in a world today where people are more often than not asked to evaluate their surroundings for a variety of reasons. This critical kind of rhetorical reflective approach to evaluation advocated here could empower students to shape their educational environment as well as learn the process of using it as a way to conceive of and evaluate other contexts in which they are asked to be responsible citizens, workers, or participants. The experience they gain in the composition classroom of critically and rhetorically reflecting will give them confidence and strategies to continue the process in environments where evaluation is desired or needed. Where else, if not the composition classroom, will students get the foundation for this kind of composing?

This foundation can be established with students first learning what it means to reflect within the framework of rhetoric. Moreover, the communicative actions students rhetorically reflect upon and respond to in their own modes of communication do not have to be limited to teacher-student interaction. Students can learn to reflect on each and every kind of communication they enter into, whether through face-to-face encounters, or through other modes of communication. Rhetorical reflection can and should extend to reading and reflecting upon many different communicative events.