Analysis

Conceding the unscientific nature of this survey and the self-selected nature of the respondents, it is difficult to make any hard-and-fast claims about the results, but I do believe that it does support the hunch that writing centers, in general, are claiming not to see rhetorical media texts at the rate they are seeing so-called traditional academic texts. That claim, of course, is where we come face to face with the problem: are the claims of not seeing such texts accurate, or are they just a reflection of the attitude that open-access writing center personnel have towards so-called non-traditional texts?

Roughly half of the respondents indicate that they work with multi-modal texts (charts 4 & 5). With that figure, we can see that rhetorical media and curriculum is having an impact on the work that goes on in writing centers. What writing centers are doing to respond to writers with rhetorical media texts, and how we are preparing tutors to respond to such writers, however, is very much in question.

In a recent chapter in Multiliteracy Centers: Writing Center work, New Media, and Multimodal Rhetoric (2010), Dickie Selfe makes the following observation that perhaps explains why writing centers are not seeing non-traditional academic texts which he calls “alphabetic texts” at the rate that we might expect in our multimodal era:

Those academic professionals and programs that choose to focus on writing and rhetoric, primarily in the alphabetic modality, will do just fine. I am convinced also that Writing Centers and the workers in them (who also focus almost exclusively on the alphabetic production modes) are likely to remain remarkably important to higher education institutions in the future. If anything, once reluctant disciplines and professionals around us are now more concerned about their students’ employees’ writing abilities than ever before….Despite frequently reported needs assessments within and outside the academic setting, however, the hard work that goes on in Writing Centers—repeated close readings and consultations, empathetic listening, collaborative problem solving, assignment translation, institutional orientation, and so on—is unlikely to be taken up to any great extent by others in higher education….Those colleagues and centers that wish to remain committed to the alphabetic, from my perspective, can afford to do so. (109-110)

Selfe’s conclusion is that writing centers can afford to ignore rhetorical media, given the strong needs (as perhaps supported by my survey) for a focus on the traditional academic alphabetic text alone. Selfe’s introductory explanation, however, seems to be a calculated effort to not anger a set of writing center colleagues who may feel that tutoring in rhetorical media is just another burden on an already over-burdened resource (a writing center).

To speak from my own informed perspective on writing center work and rhetorical media, I am not so certain. I realize that Selfe is not advocating divorcing a text from its genre or media, and, in fact, goes on to describe a methodology of response for rhetorical media, but I think it is a prevalent assumption that text stripping from a genre or media can be accomplished, and that the alphabetic text can be responded to without its genre or media context. It is not possible to strip a text away from its genre or media and offer any sort of cogent response. While one can, for example, give a writer of a web page feedback by only looking at the alphabetic text of that web page, it is not the same sort of response one would give in the context of the web page itself. Certainly, the well-established scholarship on visual rhetoric and genre theory proves that one cannot respond to a text without consideration of its genre and of its visual elements.

The efficacy of the response becomes even more problematic with other types of rhetorical media. Responding, for example, only to the alphabetic text of a video or audio project out of its specific media context may have some benefit, but will only be useful to the point where visual or aural elements have little or no impact. To do so would be quite like giving feedback to an actor giving a performance by only reading the text of what the actor performed. The analogy is a bit strained because the actor is not the author of the text she is preforming. In the case of a writer of a multimodal text, however, authorship cannot be easily stripped away. The writer wrote a multimodal text. The “performance” must be taken into account.

While de-contextualized response is a possible reality represented in the survey of types of texts writing centers respond to, there are other possible realities: does it mean that writing centers are not seeing students with such rhetorical media texts, or are we turning away students who are writing in these media?

The near 50% of writing centers working with multimodal texts appears to give some amount of relief for that worry, however, but what about the other 50%? Are they really not seeing any writers who are including graphics, charts, or employing other types of visual rhetoric in their texts? It would seem that Selfe’s cautious statement that writing center professionals committed only to alphabetic texts provides the answer: there are those writing centers out there that do not want to commit to responding to rhetorical media.

With the general proclivity of writing centers to respond to writers working on any type of writing, most, if not all writing center professionals would no doubt state that writing centers aren't seeing students with other types of texts because students aren't coming in with them--not the disturbing opposite that writing centers are turning such writers away. I’m not sure our proclivities are living up to reality, however. I wonder if Selfe’s concession to the alphabetic predicts that writing centers are running the dangerous path of turning writers away by saying “we don’t do that” or are throwing up our figurative hands and claiming not to know anything about making web pages, videos, podcasts, and other types of rhetorical media.

As Jackie Grutsch McKinney states in her chapter of Multiliteracy Centers (2010) “One of the results of not being prepared to help students with their functional technological literacy in the creation of new media texts is that others will step into that role. Students need to know how to use programs, and the need becomes intensified when the new media text is a high-stakes assignment” (215). I can hear, of course, my writing center colleagues chortling here. Really? Who will do that work? That, of course, is a realistic question and, sadly, perhaps no one will take up the work to respond to students writing in rhetorical media. While the threat of someone else stepping in and providing feedback to student writing may be, in reality, a pointless fear given economic reality and the time and effort it takes to give a writer full response, it may be more that someone else will step in with inadequate response that focuses solely on the technological aspects of writing, rather than a fuller rhetorical response that writing centers are renowned for.

In her chapter, McKinney touches upon something that is a sore point that for writing centers and working with not rhetorical media but with technology itself: that discussion of technology often devolves into a discussion of the practicality of operating certain technologies, rather than a discussion of the impact of using such technology. While I was planning this webtext, I wanted to establish the types of response that was happening in my home writing center, so I decided to conduct some informal interviews with peer tutors who worked in the SLCC Student Writing Center. Joe McCormick, one of the tutors I interviewed has a substantial history of working in technical support for various technology companies. When I asked him specifically about working with technology in the writing center, he was initially nonplussed and eventually quite forthcoming in his resistance to providing what he saw as “technical support” to student writers. He was confused, at first, because he wasn’t quite certain how responding to writing meant helping a writer with the technology. Responding to how an ePortfolio was written or how it appeared, for him, was distinct from showing a student how to achieve something specific technologically in her portfolio. For Joe, explaining the impact of a graphic element, for example, was distinct from either helping students to upload the graphic or (worse yet) doing it for them. Joe’s fears are echoed by David M. Sheridan in “All Things to All People: Multiliteracy Consulting and the Materiality of Rhetoric” (2010):

At [Michigan State University], we have been, at various times, plagued by a recurring nightmare. The details change, but the basic narrative remains the same. It goes something like this. A client makes an appointment with one of our Digital Writing Consultants (DWCs). When the client arrive, the DWC leads with our usual set of questions meant to generate a rich profiles of the rhetorical situation: Tell me a little bit about your project? Who is your audience? What is your purpose? What opportunities are there for using images, sounds, and words to reach our audience and achieve your purpose more effectively? But the client waves his or her hand through the air impatiently, cutting these questions short. He or she pulls out a photograph and hands it to the DWC, saying “I just need to scan this.”

There is a very distinct but fine line for Sheridan (or tutor Joe) on technical support that isn’t necessarily well-developed in either Grutcsh-McKinney’s recent chapter or Harris’ earlier call for “learn to use —technology as part of their writing processes” (6). As Sheridan states taking on technical support “is scary because it seems to suggest a reductive model for our Writing Center that we daily labor against, a model that reduces us to something even worse than a grammar lab: a tech lab where students come not to engage in critical conversations about communication, but to perform mindless technical procedures. Our skills-drills nightmare has been replaced by a point-and click one” (76).

In other words, the “tech help” only type of response becomes a potential reality for students who are seeking feedback on their rhetorical media writing. Lest one think that a “tech only” response is unrealistic, we can look back at the history of writing centers in general. As Sheridan reminds us, it is far easier, for example, to give a response based solely on grammar than it is to give a fuller, rhetorical response to writing. We spend a great deal of effort in writing centers to educate peer tutors on responding rhetorically to writing, and not just offering off-the-cuff grammar correction. A writing center’s purpose, in other words, is not just to correct, but to help writers learn, rhetorically. With a rhetorical media text in mind, are we prepared to respond rhetorically, or only technologically? Even worse, perhaps no one will take up the call to respond to student writers working on rhetorical media texts. What are they left with then? A purely “fix it” response or nothing at all.

Sheridan concludes that writing centers need to “locate the preparation and practice of multilteracy...consultants within the field’s newly reinvigorated concern for rhetoric as a material practice” (77) through staff education and recruiting from traditional “language-centered” units and by developing relationships “with folks in graphic design, film and video production, and other related units” (84). In other words, it is not the place of a writing center taking on responding to rhetorical media to exclusively educate tutors in such media, but to partner with other programs out there to recruit tutors who have taken course work in such media. This follows along with most writing centers who recruit peer tutors who have excelled in standard (academic) composition courses. The tutors are not necessarily learning “how to write” as much as they are learning how to respond to writers in the staff education of a particular center.

.png)

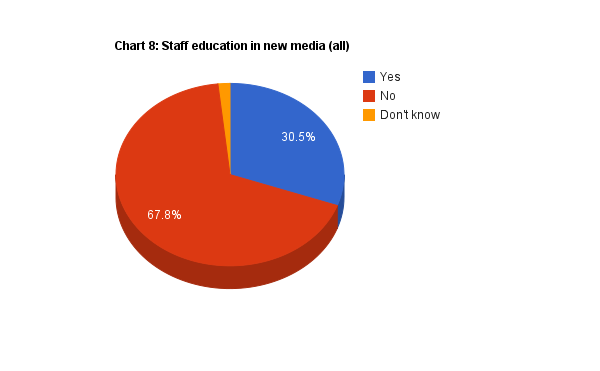

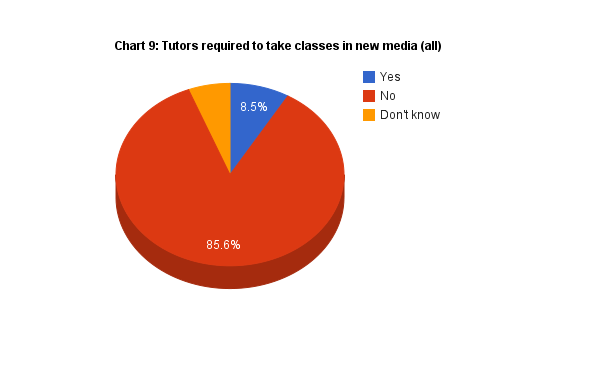

The survey I conducted, however, complicates the solution that Sheridan provides above. While 31% of all respondents offering some sort of training for their staff in new media (chart 8), this may be a response to not requiring tutors to take courses in new media since only 9% state that they do so (chart 9).

.png)

A disparity, however, plays out when we note that only 19% of open-access writing centers offer new media training and 8% require them to take courses in new media (charts 6 & 7).

A disparity, however, plays out when we note that only 19% of open-access writing centers offer new media training and 8% require them to take courses in new media (charts 6 & 7).

Next Page: Conclusion