|

Composition Studies, Heteronormativity, and Popular Culture

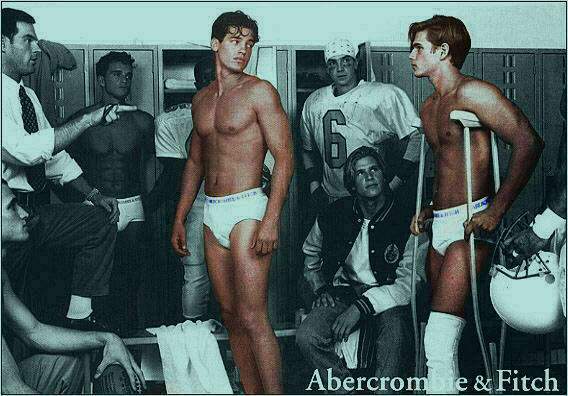

While much progress has been made toward representation of glbtq people in composition and in popular culture, we still need to encourage our students to look beyond the traditional categories of straight and gay, male and female. A queer response would be to focus on the incoherence, constructed nature, and fluidity of gender identity itself. Such a response moves us toward interrogation and critical thinking. Of course, much of what I’ve discussed in this essay exists at the level of connotation, and connotation, writes D. A. Miller, is notoriously unstable: “To refuse the evidence for a merely connoted meaning is as simple—and as frequent—as uttering the words ‘But isn’t it just . . . ?’ before retorting the denotation” (118). And such is, of course, what many students, and many people in the field of composition and rhetoric, are likely to retort. This is the difficulty inherent in any discussion of lesbian and gay representation in popular culture. In a culture that still insists, in large part, that lesbians and gay men not identify themselves at risk of physical violence, much of lesbian and gay representation in popular culture will be coded to be recognized only by the marginalized group. Such coding can be demonstrated in this ad:

While nothing can prove inconclusively that the homoerotic subtext of Friends exists, it is also true that nothing can prove inconclusively the homoerotic subtext of the Abercrombie and Fitch advertisements. The producers of the ads deny it; what more is there to say?

|

![]()

![]()

![]()