Control and Digital Underlife

Mike, as a civilian instructor, found himself initially troubled by and at odds with the Army's zeal for controlling and regulating the uses of technology. Having had excellent experiences with asking students in first-year composition courses at other institutions to create Web sites and weblogs, he considered it highly productive to ask students to interact unfettered with the outside world via the Internet. While at USMA, he worked with West Point's Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) to obtain and teach with a copy of the Al Qaeda digital publication Inspire (2010), publication of which has been restricted or suppressed because of its contents (which include bomb-making recipes). With the CTC's approval, Mike worked with students in his plebe composition classes to examine and analyze the multi-modal rhetorical moves made by the jihadist authors and publishers, but felt divided between a desire to see the value in making information as accessible as possible and an understanding of the CTC's wish to restrict access to Inspire's disturbing, hateful, and potentially life-endangering content. In Mike's perspective, if students are forbidden from making their engagement with Web sites and weblogs publicly available on the Internet, that work and engagement loses much of its pedagogical benefit.

Mike's perspective on this issue follows from Bruce Horner's observation (2000) that "the circumscriptions academic institutions typically impose on the circulation of student writing guarantee the low value of student writing in relation to other writing. In other words, student writing is evaluated as a commodity while being produced and distributed in ways that guarantee its lack of value" (p. 50). Digital technologies offer an alternative to that circumscription. In one instance, he had asked students at a previous institution to turn their essays on an article by cultural critic Thomas de Zengotita into a class Web site and put it online, and the students were delighted to have thoughtful, engaged comments in response left by de Zengotita on the course weblog. In another instance, outside visitors left supportive and encouraging comments on the individual weblogs Mike asked students to keep, prompting students to write more and to even confess that they enjoyed writing. Both of these activities increased the value of student writing, and turned it into something more than just words grudgingly exchanged for a grade.

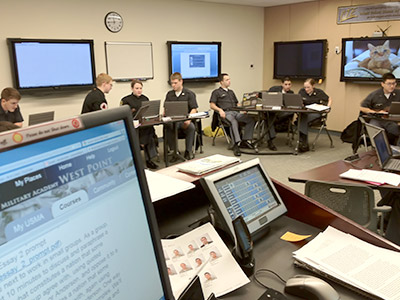

Mike found the use of powerful laptops as little more than fancy typewriters in the composition classroom to be pedagogically problematic. However, he adapted his teaching to the situation, and continues to do Web work with students in the context of West Point's non-public intranet to help give them experience with multi-modal and new media composition, and continues to use private weblogs to make the process of learning and writing visible and facilitate the social construction of knowledge. He has also directed a technology-intensive pilot version of West Point's plebe composition course wherein students composed and collaborated and communicated across a number of different information systems, resulting in measurably increased student facility in composing with digital technologies. Such pedagogical activities illustrate the way institutional pressures shape pedagogy even when one has access to a wealth of technology. At the same time, though, both Jeff and Mike hope that such approved uses of digital technology, as they become more widely prevalent at West Point, may in turn shape institutional policy.

They are not, however, the only uses of digital technology at West Point. Despite the fact that the Army momentarily banned YouTube, a search for "West Point" on the site reveals that cadets are exceptionally adroit and inventive adopters of digital video. Cynthia Selfe (1999) pointed in Technology and Literacy in the Twenty-First Century: The Importance of Paying Attention to the curious question of

why some technological literacy skills and practices are associated with this country's official system of literacy and literacy education (as represented in more regulated sites such as school standards and curricula, government documents on education and educational programs, public criteria for the hiring of corporate employees, or educational software products purchased for home tutoring use) and other practices--in contrast, with a system of nonofficial technological literacy (e.g., as represented in less regulated sites on the WWW, in homes, and in computer games). (p. 12)

At West Point, clearly some uses of

technology are acceptable, while others are not. Almost

all cadets have Facebook pages. Some keep weblogs and

rely on security through anonymity. Cadet companies have home pages that owe a

much more significant debt in terms of design, content and tone to unofficial literacies than to official literacies.

These unofficial uses of technology seem important in that they are practices

on the part of our students that take place beyond the physical space and

official sanction of the composition classroom, but also in that they are

literate practices that help to shape cadets' educations.

In fact, Mike

believes they fall in line with Derek Mueller's (2009) extension of Robert

Brooke's (1987) use of the sociological term "underlife"

to describe "those behaviors which undercut the roles expected of

participants in a situation" (p. 141). Mueller extended Brooke's term

"underlife" into the digital domain,

calling that "digital underlife. . . the distal and potentially transgressive discursive activities proliferated by emerging technologies" (p. 240). In

cadets' digital underlife, they "are developing

their individual stances toward classroom experience" (Brooke, p.144), and

those stances may be matters of concern at an institution privileging military

homogeneity. At the same time, cadet actions associated with a technological underlife may seem promising to instructors privileging

critical, self-aware, engaged students invested in the writing process. Access

to digital technologies, and the way those technologies make visible the

necessary balance between official literacies and a

technological underlife, makes visible the

negotiation we perform between building student identities as cadets and future

officers, and as lifelong writers. To borrow Brooke's (1987) concluding sentence, "the process of building identity is the

business we are in" (p. 152).