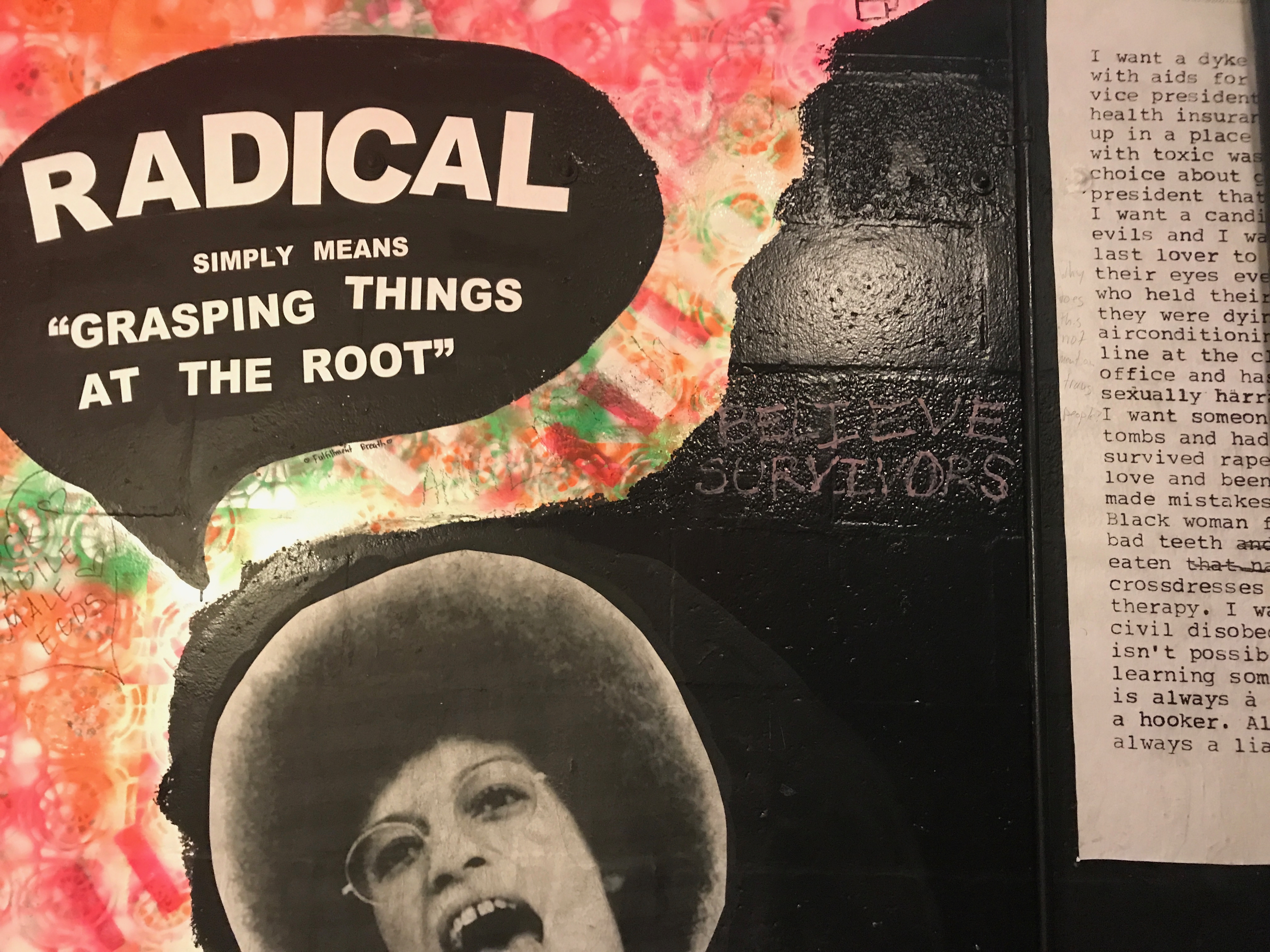

image by Laura Tetreault of a mural at The Back Door, Bloomington, IN; quotation by Angela Davis

Starting from a place specifically meant to work for trans women of color, for instance, would be such an adjustment in organizing for mainstream feminism, brought about from a shift in understanding the purview of "feminist issues." Peoples' foregrounding of impact reframes the focus of feminist rhetoric directly onto the consequentiality of that rhetoric. Peoples argues that white women need to understand the impact of "women's issues" on a variety of communities, especially those made vulnerable through intersecting oppressions, and to begin our organizing from our understanding of that impact--what mainstream feminism has historically failed to do.

Shifting our attention to the consequentiality of technofeminist rhetorics can help get us closer to a model of rhetorical activism that foregrounds accountability to vulnerable communities. Social justice rhetoric involves awareness of when to speak and when to listen, when to take the floor and when to step back and make space for someone else--strategies that women of color often learn organically as a way of moving among multiple discourses and contexts, but that white women may never learn because we assume our positions to be universal (Ratcliffe, 2005). However, to more deeply enact accountability to communities made most vulnerable in a given context, there needs to be another step--one that does not rely entirely on privileged allies asking to be educated by others, which can involve placing more labor on communities of color.

However, instead of finding ways to increase this rhetorical awareness of when to assert one's position and when to step back and listen, privileged allies often become defensive. For instance, white women often lash out at women of color and assume that women of color are insisting on white women taking on an acontextual, passive stance--that we need to be quiet or cannot assert any opinions. This exact assumption by white women came up after activist ShiShi Rose (2016) created a Facebook post on the Women's March official page titled "White Allies Read," in which Rose called on white allies to rethink their positions in relation to communities of color:

Now is the time for you to be listening more, talking less, observing, taking in media and art created by people of color, researching, unlearning the things you have been taught about this country. You should be reading our books and understanding the roots of racism and white supremacy. Listening to our speeches. You should be drowning yourselves in our poetry. Now is the time that you should be exposed to more than just the horrors of this country, but also the beauty that has always existed within communities of color. Beauty that was covered over because the need to see white faces depicted was more important.

Here, Rose (2016) is asking white women to learn about the creative resistance of communities of color--the art, books, analyses, media, resilience, and communities of activism within these communities. Many white people know the atrocities and the "horrors of this country," but we do not know how people of color have created beauty in spite of these horrors. White people need to be aware of the horrors, of course, but we also desperately need to know how to take the lead from communities who have been surviving against these horrors.

However, despite Rose's (2016) calls for us to look more at the "beauty" emerging from communities of color and to learn from it, the post was read as angry by many white women. The post gathered 7,500 Facebook reactions and comments, including many defensive responses. A New York Times article on dialogues about race in the Women's March quoted Rose's post and a response from a white woman, Jennifer Willis, who had cancelled her trip to the march after reading the post (Stockman, 2017). Willis assumed that women of color's concerns are interrupting this quest for unity and allyship. In response to this defensiveness, Rose explained in an interview with Paper Magazine (McCartney, 2017) that the automatic defensiveness of white women when asked to educate ourselves about women of color's work displays a remarkable lack of contextual awareness from white women. When we hear anger from women of color, or hear a woman of color asking us to do something, we feel outraged that someone is telling us how to act. We turn suggestions into dictates. We mis-hear women of color telling us what to do, when actually women of color are asking us to develop greater rhetorical awareness of how to use our positionalities. Rose stated:

There is room for white women to be thinking about their issues, and being uplifted by all of their sisters, and there's room for white women to be on the sidelines and allowing their sisters of color to have the floor. I think people read that article in the New York Times and read my post that I had made to white allies on the Women's March page, and I think that they thought that I was saying, "You guys just sit there, and don't ever talk, and don't talk about any of the things you go through, and just shut up." I never said any of that. (qtd in McCartney)

Here, Rose is not asking white women to be silent or to pretend to never have experienced sexism in our own lives; she is instead calling for white women to be more aware of the contexts we move through and who else is there. But to create this room, we need to focus not only on how we are crafting resistant feminist rhetorics and what resources we are using to create those rhetorics, but also the consequentiality of feminist rhetorics.

This contextualization--a form of feminist activist rhetorical awareness--is a much more powerful vision of feminist activism than the more negative ways in which discussions of racism and transphobia are usually framed. These discussions are usually framed as originating from women of color killjoys, as negative insertions into positive feminist spaces or as dangerous breaks in unified struggles. This framing of discussions of race in feminist circles as negative is repeated in headlines surrounding the Women's March, such as "Women's March on Washington Opens Contentious Dialogues About Race" (Stockman, 2017), "March on Washington Provokes Heated Debate on Class and Privilege," or "Race and Feminism: Women's March Recalls the Touchy History" (Bates, 2017). Discussions about race and feminism are "contentious, "heated," "touchy."

It tells us something important that these discussions are connected consistently with negatively inflected emotions. Heated connotes anger, while touchy implies someone may be acting too sensitive. Ahmed (2017) wrote: "When feminists of color talk about racism, we stop of the flow of a conversation. Indeed, perhaps we are the ones who interrupt that conversation. The word interruption comes from rupture: to break. A story of breakage is thus always a story that starts somewhere." Again, race is an interruption into an assumed feminist unity.

image by Laura Tetreault of a Black Lives Matter wall mural in Bloomington, IN

Conclusion

The real silencer of conversation is not women of color's commentary, but white women's defensiveness. It is all the more troubling that our defensiveness is often cloaked under the seemingly positive idea of "unity." What we really need in feminist movements is neither acontextual calls for "unity" or defensive accusations of "divisiveness"; we instead need the skills and rhetorical awareness to negotiate dissent as a source of change. Conflict is an inevitable aspect of a culture inheriting deep histories of oppression, and feminist rhetorics that ignore conflict through premature calls for unity often do even more damage (Jarratt, 1991). However, privileged allies are often ill equipped to see this damage because they are focusing on their own desired impact for their rhetorical actions--such as an impact that would increase unity--and refuse or are unable to grasp that their actions have different impacts for different communities. Especially in an inequitable society, this unevenness in impact becomes an especially important component of rhetoric, including in digital spaces where rhetors become even more vulnerable to trolling and other forms of threat (Carey, 2018). To enact more responsible rhetorics, then, those who study and produce technofeminist rhetorical actions need ways to reframe conflict as an opportunity to trace the circulation of rhetorical actions' impacts on different communities, with an eye not toward preventing all conflict, but instead toward understanding how we can better enact accountability to the needs of communities facing intersecting oppressions.

Reorienting ourselves to view rhetoric in terms of consequentiality, or foregrounding impact over intention, can help us move past a location- and time-bound way of thinking about feminist "debate." Gries (2015) asked what changes when we think of rhetoric as "an unfolding event--a distributed, material process of becomings in which divergent consequences are actualized with time and space" (pp. 7-8). This unfolding and process of becoming resonates with Ahmed's (2017) concept of a crisis or breaking point as an opening, a new way of moving. Feminist rhetoric, like other forms of activist rhetoric, have no once-and-for-all resolution. However, when we develop a different orientation that views breaking points as productive, we can open our imaginations up to what new consequences might unfold for the various communities involved in the breaking point. We can create a future-oriented intersectional feminism.

This understanding of rhetorical consequences in activist movements presents rhetorics as enmeshed and interconnected, yet also changing across the contexts of communities. In contrast, one of the most striking characteristics of the photograph of Peoples and her "White women voted for Trump" sign is the disconnection of the white women in the background. They are focused elsewhere, from their vantage points unable or unwilling to see the words on Peoples' sign. Their focus in the photograph is on their phones, toward unknown connections--the friend texting, the news article being read, the selfie being posted on social media, or innumerable other options. This is not a cliched screed against technology and the ways it can divide us, but instead a provocation for technofeminist researchers to look at what we can learn about our positions from the white women in the photograph and their relations to other elements present in the composition. The white women are alone, connected to each other and the invisible interlocutors in their phones, but disconnected from the larger composition of the photograph, as white women have too often failed to see ourselves as connected to the struggles of women of color. Technofeminist researchers coming from positions of privilege need instead to understand the deep interconnectedness of all social justice struggles, and further, to enact accountability to those most impacted by complex layers of injustice.