Social Inequalities

Platforms, in their design, governance, and cultures, re/create social inequalities along axes of identity. We contend that shining a light on these social inequalities should be a guiding tenet for intersectional technofeminist work. Raising our questions regarding design, policy, and cultures, we examine Twitter, specifically Twitter’s (in)action regarding harassment, to understand how the rhetorical work of platforms can devalue the safety of users and thereby create or maintain social inequalities. Such inequalities influence the inherent “ownership” of these platforms, which manifests through a variety of economic and cultural practices including platform design and governance. For instance, although the economic dimensions of platforms such as Reddit or Pinterest attribute their ownership to an overarching company or financially invested parties, cultural practices fortified by the platform’s design and governance structures privilege certain users, giving the network a greater sense of who has cultural “ownership” of the space. Cultural ownership of Twitter, for instance, is often exercised through harassment tactics.

It is well documented that harassment has become the status quo on the internet (Duggan, 2014) and functions as a silencing mechanism to shut certain identities out of public discourse and digital publics (Cole, 2015; Davies, 2015; Gruwell, 2017; Jane, 2014a). And although harassment affects all users online, women are likely to experience more severe and sustained forms (Duggan, 2017; Jane, 2014b, Lenhart et al., 2016; Mantilla, 2015; Poland, 2016). Further, people of color are disproportionately targeted with online harassment (Citron, 2014; Duggan, 2014), particularly women of color (Mantilla, 2015), who are at risk for more intense harassment experiences as they experience misogyny in the context of racism (Bailey, 2014). LGBTQIA+ people are also at greater risk of online harassment (Citron, 2014; Sparby, 2017), and a recent survey of Twitter users who had experienced online harassment revealed that misogynistic language and homophobic and transphobic slurs are used most often in abuse on the platform (Warzel, 2016).

![]()

Aware of their harassment problem, Twitter took steps in 2015 to better assess how abuse affects the platform by partnering with Women, Action & Media (WAM), a nonprofit focused on enhancing gender equality in the media, who collected data on myriad aspects of harassment on the platform (types, reporting practices, Twitter’s responses, etc.). WAM’s analysis noted that “while Twitter is a platform that allows for tens of millions of people to express themselves, the prevalence of harassment and abuse, especially targeting women, women of color, and gender non-conforming people, severely limits whose voices are elevated and heard” (Matias et al., 2015, n.p.). As we advocate for attention to social inequalities in research about platforms, a technofeminist approach assesses how these inequalities are created and sustained. Again, we understand platforms to be complex ecosystems where multiple and oftentimes competing actors converge. In the case of Twitter, social inequalities created through abuse cultures don’t just stem from users but from the corporate entity as well through design and policy decision-making.

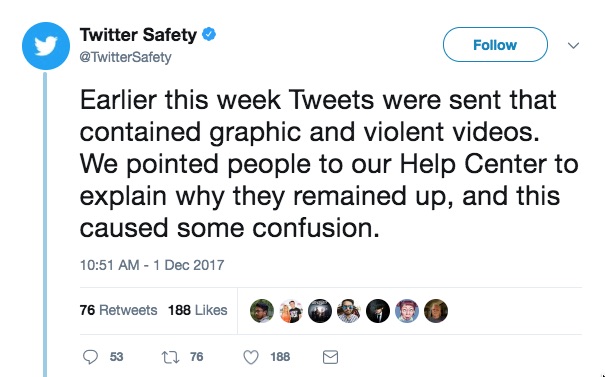

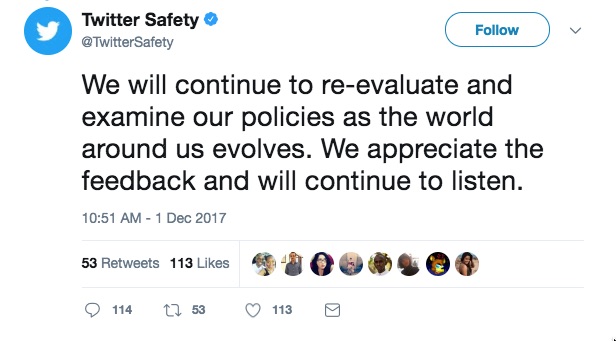

Twitter has a pattern of making decisions about the platform that devalue the safety of users, evidenced not only by their lack of action to decrease harassment but also by their inconsistent policy enforcement. Recently, the platform has taken marginal steps to provide more precise language about what constitutes abuse, yet these policies are rendered useless if not enforced consistently and in ways that are congruent to the language that defines the policy, as evidenced by a recent use of the platform by Donald Trump. On November 29th, 2017, Trump, who currently has in excess of 52 million followers, retweeted three anti-Muslim propaganda videos originally tweeted by Jayda Fransen, the deputy leader of a British fascist group. Holding Trump’s activities to the standards set forth by Twitter’s newly revised policies, many felt he (and Fransen) was in clear violation on the grounds of promoting hateful conduct and threatening a group of people based on religious affiliation. Amidst the public outcry that Twitter hold Trump accountable for his promotion of these hateful tweets, the company directed people to their Help Center (Larson, 2017), specifically the portion of their enforcement policy which says context matters in determining whether or not a use of the platform is in violation of the terms and that sometimes action is not taken on the grounds that the content in question “may be a topic of legitimate public interest” (“Our approach to policy…,” 2017). However, in an apparent reversal of their outward facing decision about leaving the videos on the platform for further circulation, Twitter Safety tweeted the following series of tweets:

Ultimately, Twitter referred to their media policy as a justification on the grounds that the videos aren’t graphic or violent enough to constitute removal. It’s important to note, however, that retaining Trump as a user is financially valuable to the company. James Cakmak, financial analyst for an equity research firm, for example, estimated that Trump is worth upwards of two billion dollars to the platform based on a number of factors including the immense amount of free advertising Twitter receives as a result of Trump’s frequent and controversial use of the platform (Wittenstein, 2017). As of May 2018, Twitter, a publicly traded company, is worth 24.34 billion dollars.

Given the subjective nature of policy enforcement and the economic interests of the company, it’s clear some users have more influence on the platform, especially those who attract monetary and gain cultural value for the platform, and therefore can, at times, circumvent or avoid repercussions for violating policies. Thus, hierarchies of users are created, widening equality gaps online. A technofeminist approach to understanding the rhetorical work of platforms is attuned to how such social inequalities are upheld through policy definitions and enforcement. Although brief, our examination of Twitter in this section reveals the nuanced ways that policy, design, and economics all interact with one another in ways that significantly affect users and the shape of the platform itself. In the next section, we examine how platform labor practices affect workers, users, and content.