In several places in What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy (VGLL), James Paul Gee mentions “embodied learning.” Gee gets to the point of what he means by this phrase in this passage on the critical roles that practice (which is not the same thing as ‘drilling’) plays in learning:

The fact that human learning is a practice effect can create a good deal of difficulty for learning in school. Children cannot learn in a deep way if they have no opportunities to practice what they are learning. They cannot learn deeply only by being told things outside the context of embodied actions. Yet, at the same time, children must be motivated to engage in a good deal of practice if they are to master what is to be learned. However, if this practice is boring, they will resist it (my emphasis, 68).

In the context of schooling (that is, formalized, instutionalized learning), "practice" may connote repetition but for Gee it really occurs when a learner desires to re-engage a challenging activity over and over again. When this happens, and Gee suggests it happens frequently when people play video games, the learning is “deep”—it is felt in, and acquired through, the body. In his book, Gee argues that video games have something to teach educators about effective learning environments. Good video games, he says, offer people opportunities for deep learning by:

- immersing players in challenges they can meet (only to enjoy to have their successes, their mastery of strategies, disrupted by new challenges) [Practice Principle and Ongoing Learning Principle]

- inviting players to extend some part of themselves (a virtual self) into the game story/world (to make, in Gee’s language, “an identity commitment” 68) [Identity Principle]

- creating situations for players to build over time the meaning of all the diverse elements of the game world/environment [Probing Principle and Situated Meaning Principle]

- making it possible and likely that players will formulate thier own “appreciative system": a social space for processing the game—in particular, evaluating players' strategies and the game’s challenges [Affinity Group Principle and Insider Principle]

For Gee, learning neccesarily involves practice--the revisiting of puzzling or problematic situations "in the context of embodied actions"--but this intellectual/physical process of re-engagement can be boring. So, what makes practice pleasurable?

Looking at the four principles above, it is possible to suggest that practice is pleasurable when it involves people in making choices that reward them somehow--choices about

who to be: (imaginative projection: some participation in story-telling or drama)

what the rules are (game recognition: the mental labor of identifying problems and how to solve them)

how to adapt (or improvise on) the rules to suit a particular context (game elaboration: some kind of recoding of some elements of the game)

Although recently there has been a great deal of research and curriculum reform aimed at getting students more involved in their learning, the "pedagogies of engagement" (i.e., cooperative learning, collaborative learning, problem-based learning, experiential learning) could pay more attention to the question: What makes practice pleasurable?. The theorizing of fun (called "ludology" by game theorists) has a great deal to offer discussions of improved ("learner-centered") educational models, which sometimes read like Fredrick Taylor's descriptions of how to manage the "wastes of human effort, which go on every day through such of our acts as are blundering, ill-directed, or inefficient" ("Introduction"). For example, in a recent article for Journal of Engineering Education, the authors write that "at the heart of a student-engaged instructional approach" is the "simultaneous presence of interdependence and accountability" (2005). Smith et al. propose to enhance engineering students' enagement in the discipline with cooperative and problem-based learning:

Cooperative learning is the instructional use of small groups so that students work together to maximize their own and each others' learning. Carefully structured cooperative learning involves people working in teams to accomplish a common goal, under conditions that involve both positive interdependence (all members must cooperate to complete the task) and individual and group accountability (each member individually as well as all members collectively accountable for the work of the group)..

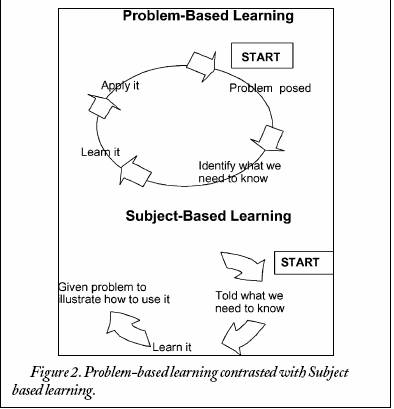

To represent problem-based learning, the article presents the following diagram:

Note how the better managed process (top) is literally circumscribed--made into a tight circle.

Decentering the classroom is a risky business for students and teachers and so it makes sense that faculty feel compelled to manage and schematize the ways in which learners become engaged. It is important, however, not to limit our understanding of student engagement by focusing soely on what the teacher does to choregraph and assess learning. Engagement should have something to do with fun, with play. As John Dewey writes in Experieince and Education:

Perhaps the greatest of all pedagogical fallacies is the notion that a person learns only that particular thing he is studying at the time. Collateral learning in the way of formation of enduring attitudes, of likes and dislikes, may be and often is much more important than the spelling lesson in geography or history that is learned.

Gee's notion of embodied learning is important for anyone interested in pedagogy because it directs our attention to the issue of how feelings are involved in (collateral) learning, in particular, in the pleasurable revisiting of puzzles and problems.

There are, of course, other contexts for pleasurable learning than the one that interests me here: practice. Intricatedly plotted soap operas like "The Sopranos," Steven Johnson writes in Everything Bad is Good For You: How Today's Popular Culture Actually Makes Us Smarter (2005), are enjoyable largely because the viewer must fill in a lot of information "that has been either deliberately witheld or deliberately left obscure" (63). College composition, long regarded by students and teachers alike as the painful disciplining of an individual's scrambled, idiosyncratic thoughts into uniform academic prose, has been reformulated in a number of recent teaching guides that enlarges upon the ways in which learning is embodied. Refusing the academic/personal binary of personal versus academic writing that seems to always construct pleasure as matter of writing without constraints, these pedagogies treat composing as a process that is at once scripted and improvised, with a good deal of collateral learning occuring as writers

- tune in to the metabolic rhythms of writing (Perl's Felt Sense: Writing with the Body)

- play around with the "generative magic" of prose sounds (Johnson's The Rhetoric of Pleasure)

- perform a variety of critical agencies (Ulmer's Internet Invention)

Drawing on research in experiential learning and game theory, this essay aims to explain some of the pleasures of practice by looking first theoretically at the question of what does it mean to embody learning and then concretely at a case study of Oliver, a six-year old who invented a card game. My interest in the emotional aspects of learning in general and writing in particular is driven both by my past experiences with learning that takes place in contexts other than traditional schooling and my present concerns with improving what I take to be an extremely important assignment in English 111: the literacy autobiography.

Plan of the Essay

In ther first section of the essay, I situate Gee's notion of embodied learning in relation to developmental theory and ludology; the second section applies my hypothesis about the pleasures of practice to a case study of a six-year old (Oliver Dickson) who made up his own card game called "Civil War." A (9 minute) video documentary about the game, created at “DMAC” (the Digital Media and Composition Institute at Ohio State University) in the summer of 2006, is available here. The last section offers concluding thoughts about new directions for the Literacy Autobiography Assignment in First-year Writing.

One: Situating Embodied Learning

-

Identity and Learning: “Follow What I Am Doing: Do The Rules That I’m Doing: It’s Very CoM-pli-cated”

- Producelike Behavior: "Why Do The Make Queen Better Than Jack?"

- Conclusion: "The Bricolage, The Music, The Movement"

Three: Implications for the Literacy Autobiography Assignment