Figure 2. Image showing #womenswave appearing on merchandise (flags and a button) for sale at Lake Eola Park on Jan. 19, 2019.

An Augmented Thick Description of #womenswave

L. Corinne Jones: University of Central Florida

Introduction: Invention, Spread, and Consequentiality

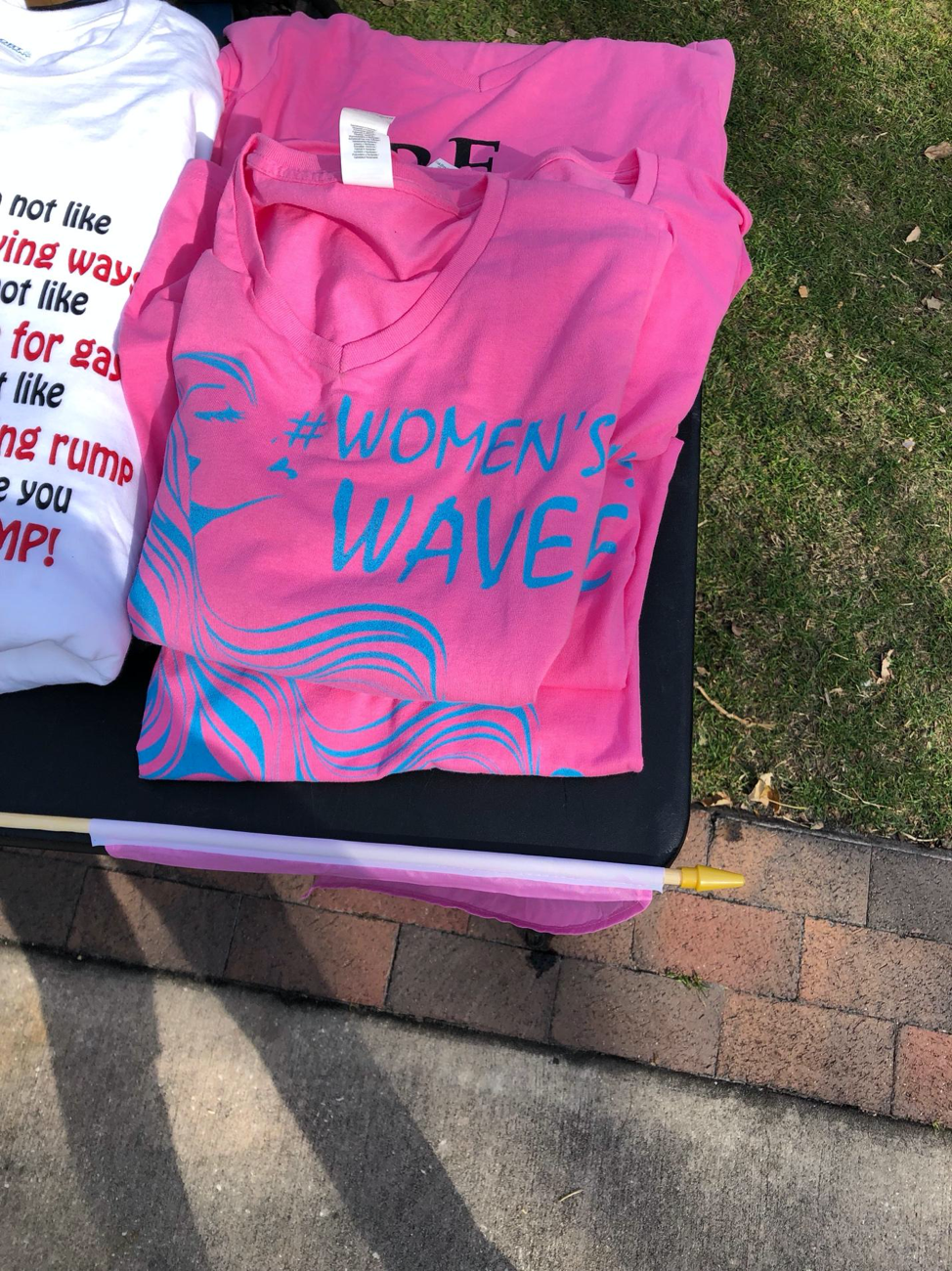

As noted by Beveridge (2017), Navar-Gill and Stanfill (2018) and Wolff (2018) large-scale quantitative data can only tell part of the story. In my qualitative analysis, #womenswave appeared on t-shirts, flags, buttons, and other merchandise sold at the rally after the parade.

Figure 2. Image showing #womenswave appearing on merchandise (flags and a button) for sale at Lake Eola Park on Jan. 19, 2019.

Figure 3. Image showing #womenswave appearing on merchandise (t-shirts) for sale at Lake Eola Park on Jan. 19, 2019.

While these examples show how the hashtag moved into the material world as Edwards and Lang (2018) contend, my qualitative data suggests that #womenswave did not provide a topoi, or vantage points from which people could think (122-123). Additionally, though it did clearly function in a greater collective of the women and allies who marched, that collective was loosely based, and, as previous criticisms of the march suggest, fragmented. Please click on the links below to explore my three main conclusions.