The field notebook, ancient genre that it is, has become a highly conventionalized and often romanticized artifact in the work of a scientist; as one of my colleagues in the field of biology put it emphatically, “My field notes are my connection to Darwin!” Genre theorist Peter Medway notes that personal (and I would add, professional) identity formation is shaped by discourse community rules and practices such as taking field notes; moreover, such personal identity formation motivates the writer to participate in the construction and maintenance of a shared communal identity in responding to the genre’s recognizable exigencies—recording, reflecting upon, and sharing observations in the field.

My first research trip to the San Juan Mountains was exploratory in nature, consisting of a series of day-long observations logged on a digital voice recorder, numerous digital photographs, and several informal interviews with students and faculty during hikes in the mountains.

Photo 3: Taking lecture notes with traditional field notebooks, Durango, Colorado

My observations revealed that students were often personally attached to their manuscript notebooks, and did indeed use them to reflect in a contemplative and personal way on the results of their observations. They were given a list of what to include in their field notebooks, and cautioned against making any erasures, as in at least one case, a field notebook became a legal document used as evidence in a court of law. They were told that changes to manuscript field notes should not occur in the text of the notes; any changes are only reflected in the right-up of the final report. No conclusions should be drawn in the field based on recorded data, nor should conclusions be entered in the notebook itself. Analyses and conclusions are reflected only in the right-up of the final report, which is a separate document. When I asked one student if she thought this might not work to shape her conclusions in a different way than if she were to engage in more data interpretation while in the field, she replied that the data doesn’t change upon analysis, no matter when that analysis occurs: “What you see is what you see.”

Photo 4: Entering data in the field

Students made use of the notebooks in unexpected ways as well; for example, as flat planes for performing dip and strike exercises to determine the stability of rock faces; I noticed one student using his magnifying glass as a bookmark for the notebook, and also using the notebook as a safekeeping place for the magnifying glass. Some students even used their notebooks as braces for shifting their weight against the rocks while climbing. Typically they hold 3 or 4 objects at once while climbing—the field notebook, a pencil, the magnifying glass they need to look at the rock sample more closely, and a rock hammer. One student carrying two field notebooks indicated that he had large handwriting and was almost out of room in his first field notebook. Another carried a duplicate notebook as backup in case he lost one of them. Often they stop to write in the notebooks during recording activities that involve climbing, so it’s quite an impressive balancing act.

Photo 5: Chiseling a rock sample, notebook in hand...

I had promised the geology professors that I would interfere as little as possible with students’ work in the field, so I often spoke with them during lunch and other breaks throughout the day. In addition to questions about their traditional field notebooks, I asked them to consider what affordances and constraints they felt digital notebooks might present for their work. Most initially balked, citing the possibility of damaging valuable equipment (although they were already using sophisticated technology for mapping purposes), or losing their notes as a result of technical malfunction. Part of the usefulness of the traditional manuscript notebooks from the students’ point of view is that they make it easy for professors to evaluate what students are doing—“We need the field notebooks because we have to turn them in and they get graded,” something they couldn’t seem to conceptualize would be possible with digital field notebooks. I questioned professors as well on occasion and was given a similar response on the same subject of notebook evaluation: “Well, I usually sit in one of the vehicles with a stack of field notebooks next to me on the seat. As I grade each one, I toss it into the back seat. I couldn’t do that with a digital field notebook.” The possibility of file sharing rather than having to handle the digital device itself seemed to escape him. Some students indicated that they would be able to use voice recording equipment effectively in the field for taking measurements that were recorded in the field notebooks, and when I questioned them about the possibility of using drawing programs available on their pocket PCs for sketching in the field, they seemed to accept the idea, but not eagerly, and they did not attempt to use them to draw.

Overall, my preliminary findings on this first trip indicated that the growing use of digital technologies to represent information in the geosciences presented a timely opportunity to explore the possible benefits of producing digital field notes. Equally tantalizing was the opportunity to consider the ways that digital field notes might work to transform the communicative interaction of scientists who use them.

Photo 6: Harbinger of an abandoned tradition...

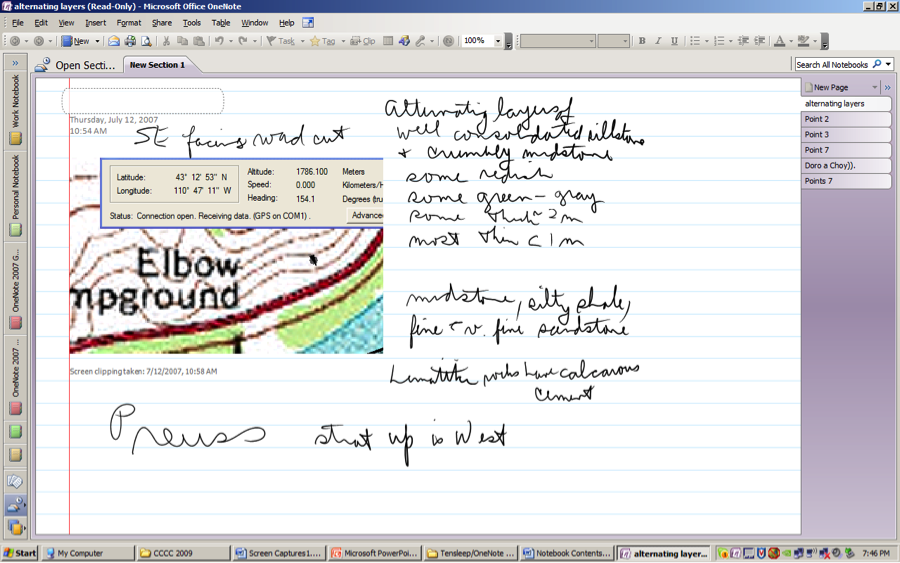

Two summers later, I made a second trip out west, to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and surrounds with a different group of geology students from the University of Michigan who actually did use specially designed Geopads to compose digital field notebooks. Geopads are tablet PCs loaded with Microsoft OneNote software, along with GPS mapping tools and a variety of other programs, including email capability. They can be strapped to the upper body in a sling-like, canvas support system that allows for both note-taking and safe hiking and climbing in rugged locations.

Photo 7: First attempt at digital notebook use in the field, Grand Teton National Park

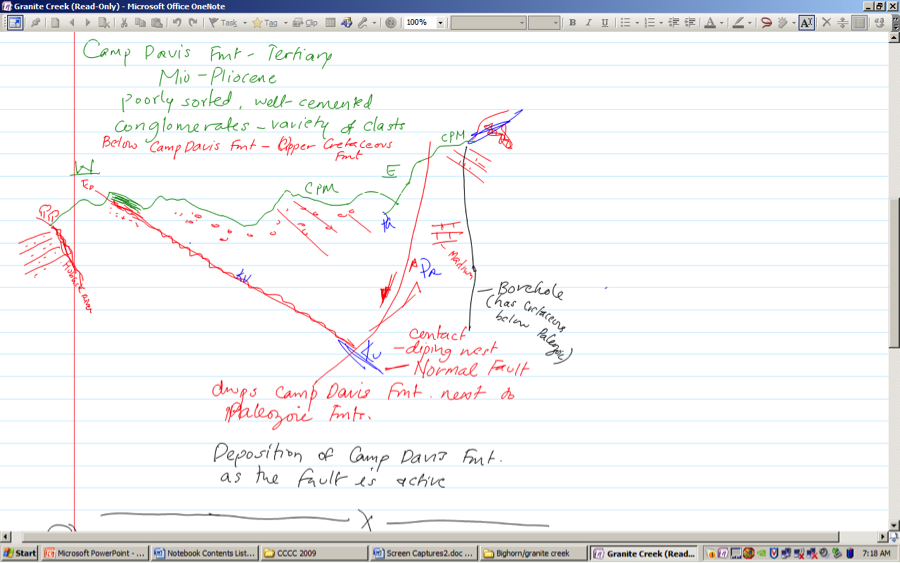

Compared to traditional field notebooks regularly used by geology students, and apart from providing the striking multimedia and communication advantages mentioned earlier, digital field notebooks also possess certain inherent, shared characteristics with traditional manuscript field notebooks. For example, both fulfill users’ common social motivation to perform a task required in an institutionalized situation, and answer their need for personal identification with the members of a professional community. Within the geology discourse community, both construct raw data for several future forms of communication within that community, within the wider scientific audience, and at some point in the communication channel, even with the general public. And both exhibit some characteristics of what Peter Medway (2002) has called a “fuzzy genre”: striking diversity in physical format; internal organization; the amount of use; the amount, type and style of drawings; the relationship between drawing and text; and patterns of textual and linguistic organization. Students are instructed in both cases to keep their notes and drawings “organized and legible,” yet I found no formal or replicable pattern of organization to appear in either of the two types of field notes.

Photo 8: Digital Representation of UM's Camp Davis Fmt at Jackson Hole, WY

On this second trip, just like the first, my data collection consisted of a series of day-long observations of students using their Geopads, numerous digital photographs, and several informal interviews with students and faculty during hikes in the mountains of Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. However, I had much closer contact with these students, as we spent 24 hours a day together for 8 days. On the second day of our travels, Professor Niemi of the University of Michigan Geology Department distributed the Geopads and harnesses for the first time to students while we were breaking camp and loading up the travel vans.

Photo 9: Breaking down camp in the morning and donning Geopad slings

Each of the computers had been given a human name, and was assigned to students for the duration of the trip. Naming the computers makes them more personal, I was told. Only one student continuously referred to her computer by name, Maxfield, and refused to use the harness, often carrying it against her body as one might carry an infant or a small child. Interestingly, she was the most reticent to use the Geopad for its intended purpose compared to other students, making it clear on many occasions that she preferred the traditional notebook.

Photo 10: "Maxfield" gets a hug!

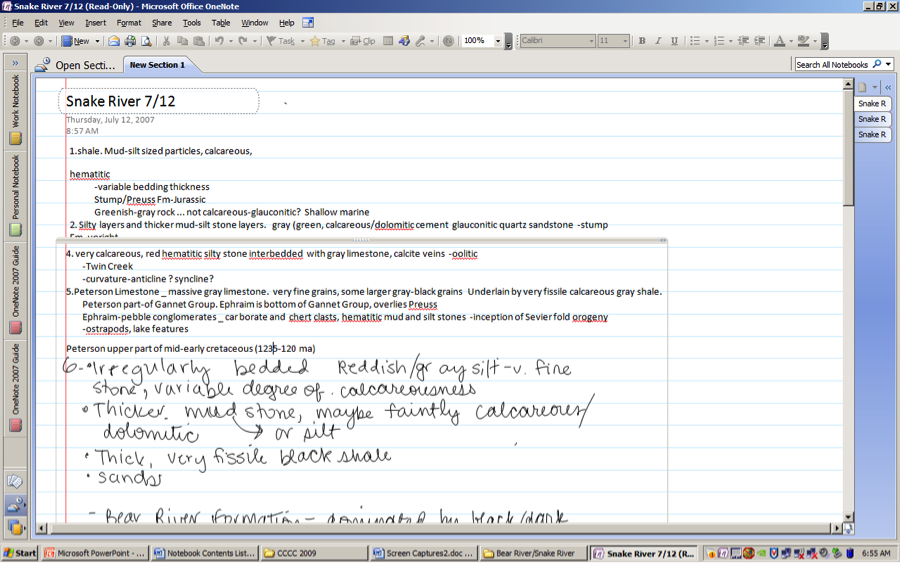

After taking to the road, we stopped to orient students to the devices and had some difficulty due to inconsistencies in equipment software versions. Students opened the Visual GPS program and the ArcGIS program, which when integrated, allow students to tap with a stylus on sections of their maps and receive location information such as coordinates in pop-up windows. They can also enter information themselves to the maps in this manner. Next they were briefly oriented to the software they would be using to inscribe field notes—Microsoft OneNote. The insert menu for OneNote allows for embedding of video, audio, digital photos and other files; screen clips from the web or other mapping applications and files; and blogs to include commentary from other users, should they choose to post their field notes to the web. However, sadly, none of these features were used or encouraged to be used during field work; it was as if the old medium of the traditional field notebook were simply being poured into the new, as is so often the case with migration from one medium to another (Bolter 1999). Very little remediation of the notebook seemed to be given any thought. One feature which did receive some attention from the instructor was text recognition, which converted students’ handwritten text to print, and in examining their digital notebook files I found that one or two students tried this occasionally, but then returned to their own handwriting for the remainder of the trip. Most felt the text converter was too labor intensive, and didn’t feel there was much value added.

Photo 11: Using the text conversion feature in MS OneNote

Photo 12: Working with Geopads at 13,000 feet, Bear Claw Mountains

Other likes and dislikes students reported to me were:

1. Some disliked writing on the Geopad with the stylus because it was too slow.

2. Screens were difficult to see in the sun.

3. Holsters required adjusting when switching from writing to drawing.

4. Text conversion was difficult with the text predictor engaged as no science vocabulary had been added to the dictionary.

5. One student felt a loss of ownership of the notes. He explained, “When I write on the computer, it’s the computer that’s interpreting what I write.”

6. The Geopads were too big, too bulky, and the batteries didn’t last long enough.

7. Some students said they drew more with the Geopads, others less.

a. Those who drew more gave reasons such as: the ability to use color, larger drawing space, no smudging, capability to shrink or expand drawings (to make more room for text or to show more detail), and drawings (as well as text) could be moved around the screen.

b. Those who drew less cited: more difficulty shading drawings to indicate texture, less control “like drawing with a big crayon,” more difficulty connecting lines, less friction, and a time lag between pen motion and object appearance on the screen.

8. One student felt the digital medium would make better organization of data possible.

Photo 13: Back to the sun, shading the Geopad screen for better visibility

Dr. Neimi also raised an issue that demonstrates how digital field notes may have the capacity to transform how field work itself is spatially conceptualized by geologists. He explained that the mapping program presents several topographic layers of information to students at once in separate, simultaneously viewed windows; normally, each layer of information would be dealt with separately in sequence. He also noted that the field activites and note-taking exercises involved in mapping are performed sequentially and thus produce a kind of gradually evolving narrative of experience and information accumulation which, according to received practice in the field, must be preserved in order to construct knowledge accurately. According to Dr. Neimi, digital mapping and note-taking may undermine this established process of knowledge construction, not only because of the non-sequential, simultaneous viewing capabilities the mapping program affords, but also because the editing capability of the OneNote software may tempt students to revise their notes while still in the field, and thus fail to preserve a sequentially acquired understanding of the terrain.

Photo 14: Embedded real-time GIS imaging in MS OneNote

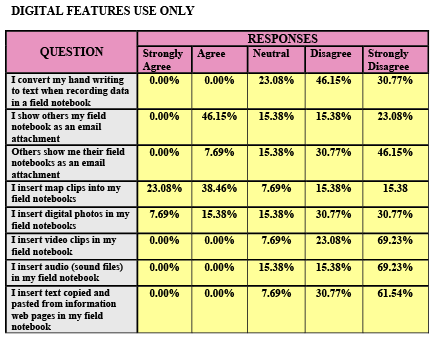

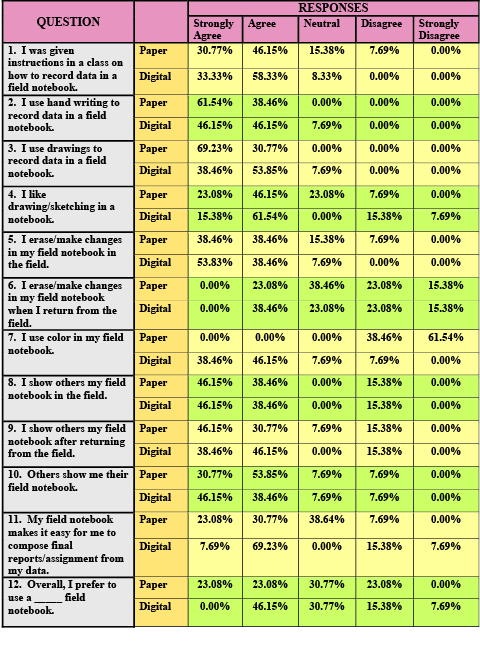

The following survey results rendered in tabular form were collected from University of Michigan geology students using an online survey I composed and made available to them at Survey Console, www.surveyconsole.com.

Figure 1: Manuscript field notebook survey results