In any research project, I use multiple methodologies, weaving them in what I hope are creative and useful ways to provide a richer description of my observations, descriptions, results, interpretations and conclusions. In this study, my primary methodology has been ethnography. As Doheny-Farina notes (1993), qualitative, ethnographic studies of writing have helped inform the study of writing in a variety of nonacademic settings, including scientific writing. Like Doheny-Farina, I agree that researcher claims made about the field are always rhetorical in nature, and so the exposure of the personal positions that guide us in our ethnographic work is an ethical requirement—one upon which our strongest authority rests (Doheny-Farina, 1993). Ethnographers not only cannot, but should not attempt to stand above or outside the subjects of their research (Ellis, 1996). However, at the same time we acknowledge our particular perspectives and practices as researchers, we must avoid privileging those perspectives and practices over others. Newer ethnographic studies not only admit, but foreground the view that researchers are not invisible; they leave traces of their convictions in the texts they construct and by refusing to mask or marginalize their presence in those texts, they accept and are personally accountable for the impact of their presence (Van Manaan, 1988). Moreover, new ethnographers are pragmatic; their focus is not on questions about truth or how to get at the truth, but rather on how their experiences and reports can be used. They hope that their work can assist others in understanding what new directions to take (Van Manaan, 1988).

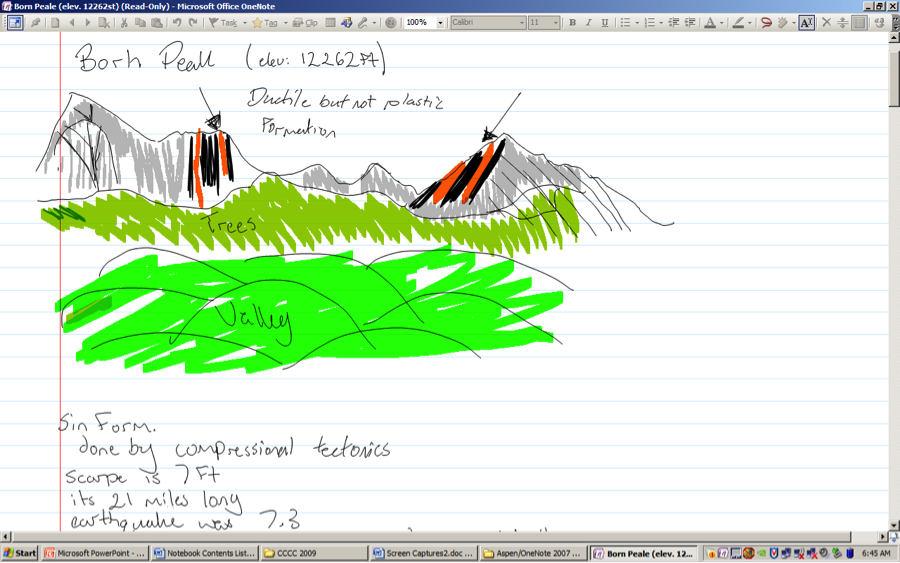

In accordance with these ethical prescriptions, I want to make clear that I avoided the distanced observer stance in this research and attempted to become actively engaged with participants in the geology field course; I carried with me into those relationships the conviction that geology field notebooks, which have been constructed in manuscript form for at least 1,500 years (Sigurdsson, 1999, p.73), will, like so many traditional genres, eventually be remediated by information technology. These small, bright yellow and orange paper notebooks written by hand on waterproof pages will, in the not-so-distant future, be replaced by digital field notebooks that include color drawings, print text, sound files, photos and video, composed in the field on tablet PCs or similar technology, and shared with a variety of academic and non-academic collaborators via email and the WWW.

As a second methodology, my study makes use of North American genre theory. In North America, contemporary genre theorists study texts as products of recurring social actions. The purpose or action that is accomplished by a genre’s use, together with the interactions of its users, is the unit of analysis; these users are also understood to be acting as members of particular systems of activity (Miller "Genre as Social Action" 266). Thus the researcher must also examine the role writing plays in those activity systems, especially where it mediates work in powerful ways, such as the work of knowledge making (Russell, 1997). And as Geisler and Bazerman, et al. note:

“Understanding of genre is crucial to moving activities and social networks into electronic environments. The use of prior forms for early recognizability needs to be balanced with innovation that restructures communicative forms, social relations, and activity (Agre; Bolter and Grusin; Gurak; Yates). The design of IText tools for the production, access, circulation, and use of information needs to accommodate both continuities and change in genre (p. 277).

Unfortunately, much genre-based research frequently “lends itself to a mode of reporting that reproduces the dominant discourse of its research site, and spends relatively little energy analyzing the modes and possibilities for dissent, resistance, and revision,” (Herndl, 1993, p. 349). However, I have deliberately looked to uncover those very modes and possibilities for dissent, resistance, and revision within the activity systems and discourse community of geology. The concept of a discourse community itself can present an unrealistically rosy view of togetherness, support and identification, obscuring “the [group] dynamics of restriction and regulation, the [tacit] means whereby a community enforces its [particular] discourse conventions and its methods of producing knowledge,” (Pare, 1993, p. 111). Such regulation influences not only the composition, interpretation and use of community texts, but more profoundly, the thinking of community members.

In this study, I regard both traditional (Photo 1) and digital field notebooks (Photo 2) as cultural artifacts: “Calling a genre a cultural artifact is an invitation to see it much as an anthropologist sees a material artifact from an ancient civilization, as a product that has particular functions, that fits into a system of functions and other artifacts,” (Miller, 1994, p. 69). Cultures, including those created and maintained by scientific disciplines such as geology, can be characterized and analyzed using their genre sets as tools of analysis. “The genre set represents a system of actions and interactions that have specific social locations and functions, as well as repeated or recurrent value…” (Miller, 1994, p. 70). I am also interested in employing this method to pursue the questions posed by Freedman and Medway (1994) in their book, Genre and the New Rhetoric: How do some genres come to be valorized? In whose interest is such valorization? What kinds of social organization are put in place or kept in place by such valorization? Who is excluded? What representations of the world are entailed?” (p. 11).

Finally, I include as a third methodology, Activity Theory, which considers how the relationship between humans and the objects of their environment are mediated by the tools they use. Field notebooks, as tools of scientific observation, shape both the internal mental processes of their users as well as the external reality they study. According to activity theory, tools: . . . usually reflect the experiences of other people who have tried to solve similar problems at an earlier time and invented the tool to make solving those problems more efficient. These experiences are accumulated in the structural properties of tools as well as in the knowledge of how the tool should be used. Tools and the user relationships they mediate are created and transformed during the development of the activity itself ... [and thus are] a means for the accumulation and transmission of social knowledge.” (Ryder, 2007). Admittedly, I have just begun to scratch the surface of how digital field notebooks have the potential to, and in some cases have already begun to mediate the relationship between geologists and the environments they explore, study, and report on to the scientific community, the commercial fossil fuel industry, and others. My hope is to further this exploratory research done with geology students to professional work done in the field by practicing petroleum geologists. It is my hope that this multiple-methodological approach to analyzing the transformation of the geology field notebook will serve to enrich my exploration of its migration, and suggest useful approaches for future research.

Photo 1: Traditional field notebooks at Jackson Hole, Wyoming