The Arab Spring: Revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt

Bouazizi

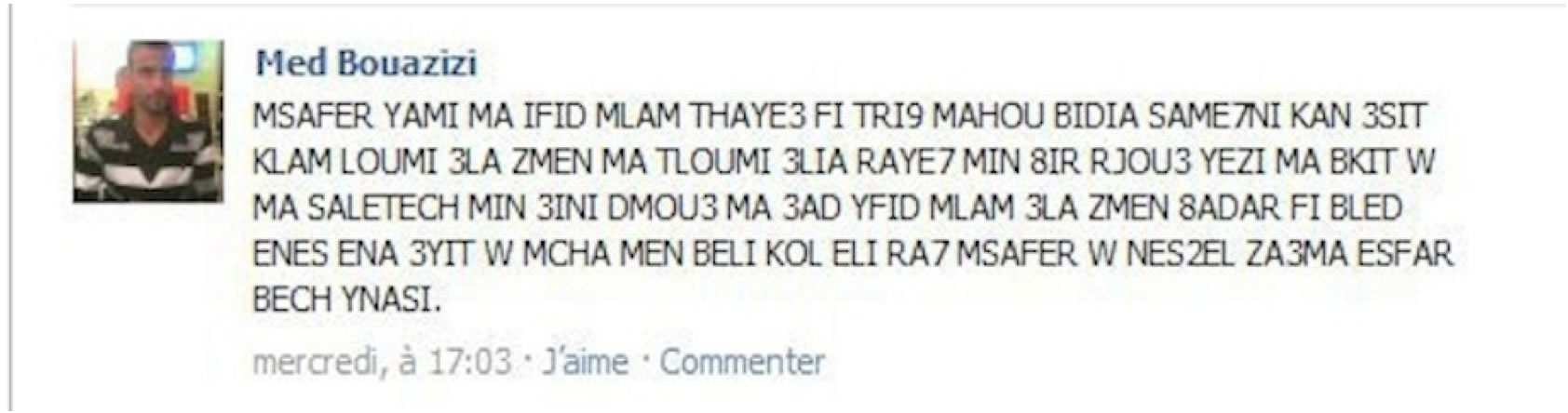

I will begin with the spark that set the Middle East alight. Mohamed Bouazizi lived in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia. His crime was that he sold groceries without a permit in order to support both himself and his family. But when his produce and scales were confiscated by local police officers, he could no longer stand the injustice of his circumstance. Having lost all hope, he set himself on fire, thereby igniting the Tunisian revolution. His last words still echo on Facebook:

“I will be traveling my mom, forgive me, Reproach is not helpful, i am lost in my way it is not in my hand, forgive me if disobeyed words of my mom, blame our times and do not blame me, i am going and not coming back, look i did not cry and tears did not fall from my eyes, Reproach is not helpful in time of Treachery in the land of people, i am sick and not in my mind all what happened, i am traveling and i am asking who leads the travel to forget.” (arabcrunch.com)

|

| Image provided by arabcrunch.com |

A photo of Bouazizi’s burning body was allegedly taken with a mobile phone and sent across Facebook. His visible sacrifice then triggered a string of events that has changed at least two Middle Eastern nations with perhaps more to follow. Not far away in Egypt, Mr Abdel-Monaim also set himself on fire in an apparent effort to raise awareness about injustice in Egypt, much as Bouazizi had in Tunisia. Though he was likely a contributing factor, others claim that it was the mysterious death of Khaled Said, and the Facebook campaign that followed, that created the climate for the Egyptian protests. Said’s death was likely caused by Egyptian police officers wishing to silence his political dissonance, and though it cannot be sure which was the catalyst (if not both), what is sure is the result.

The Middle East is changing—Tunisia and Egypt in particular. And it is exciting. From these ashes the world bore witness to two movements of relatively non-violent resistance, and each was successful in transforming their respective governments. Journalists, advocates, and politicians largely credit the success of these movements to new media, calling it an “internet revolution” or, as Egyptian revolution leader and Google CEO Wael Ghonim would call it, “Revolution 2.0.” But others are not so convinced, and this is where I feel rhetoric and composition can play a key role. We know that that invention of new technology correlates highly with social change (Manovich, 2001, pp. 41). Composition studies is looking at the affordances of new media, and we are asking questions about what new media can do, who has access, and how we can incorporate new media in the classroom, often with student agency in mind. I agree with Anne Wyosocki (2004) when she says that we need to teach students to be critical of technology so as to help our students compose for the future, and as to empower them against becoming uncritical consumers of technology (pp. 1-23). The test of new media applications can be found in the materiality of their applications. Thus I ask the question, what can the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt teach us about the affordances of new media?