The Arab Spring: Revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt

|

| Facebook image, unknown author |

Identity

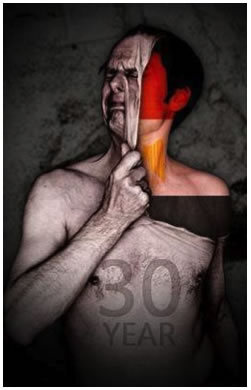

A unifying identity is a significant factor of mobilization potential, and social media creates a platform to both construct and communicate identities to others. This is where composition plays a key role. For example, consider the image you see to the right. The imagery here affords a framing of the message that the older regime is being shed in favor of a new Egyptian identity. Here we see an Egyptian man with the face of Hosni Mubarak. The image portrays a shedding of Mubarak’s face in exchange for a more youthful look, which possibly symbolizes the youth of the internet protesters. This youth is also adorned in the colors of the Egyptian flag while Mubarak’s face is not. This reinforces the idea that Mubarak is not representative of this new national identity that the Facebook community, and the movement as a whole, is creating. This composition both reflects and reifies the identity of the movement.

|

| Facebook image from a Tunisian protester (English added) |

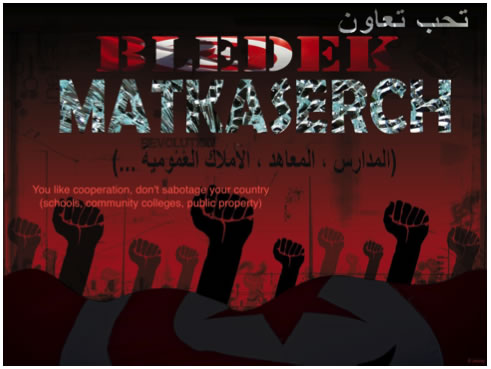

The same kind solidarity can be found in Tunisia. The image on the left, also shared through Facebook, shows fists raised in the air as a sign of protest raised above the Tunisian flag. Lana Oweidet of Ohio University was kind enough to translate the Arabic in this image, which roughly translates as: "You like cooperation, don't sabotage your country (schools, community colleges, public property)." The message here seems to be both clear and poignant. The text is encouraging protesters to abstain from damaging the infrastructure of the country. The activities of the protesters are encouraged by the symbol of the raised fists, the symbol of revolution. The message is also that of unity signified by the Tunisian flag. To me there is little question that the identity of Tunisian nationalism is at the heart of this image. It encourages a respect for the land of Tunisia signified by the flag being below the fists and in combination with the alphabetic message to respect the infrastructure of the nation, but the fists above maintain that the movement is paramount.

In addition to the national identity there is also the martyrdom imagery that is disseminated through social networking. Both Tunisia and Egypt are predominantly Muslim countries where the power of the martyr is a well-documented source of influence, for good or evil depending on whom you ask. But in the case of Tunisia Mohammed Bouazizi became the image of government oppression. The pain that was inflicted upon him was thus equated to all Tunisians. The same is true for Kahaled Said. His image became the symbol of government violence, murdered by the very police force who would earn international recognition for their acts of violence against protesters through the activism of social networking, news media, and the composition of both, with a captive audience on the ground gaining fuel from the recognition.

One final criticism of the efficacy of social media is whether it is tied to the same forces as conventional media. Natalie Fenton (2008) warns at how capitalist market forces influence the spread of information. By Drawing on works by Stuart Hall, J. Habermas and others, Fenton draws attention to how journalism, through conventional outlets such as television, radio and etc., is geared more towards consumer consumption as entertainment rather than informing the public, an attitude that inhibits critical engagement and facilitates dramatization and oversimplification of complex matters--with an emphasis on a vivid polarization that alienates people from political communication (pp. 230-232). There was certainly plenty of information censorship in both Tunisia and Egypt, both in the digital sphere and on the ground. But in Egypt’s case specifically, capitalist forces actually worked against the internet crackdown. As one communications analyst notes: “The government seems to have put itself in a tough position, as the Egyptian working week begins tomorrow, and with it, incredible disruptions to Egypt's economy and debt rating from the loss of Internet and mobile communications.” Egypt could not maintain its internet silence without damaging its economy and affecting the other economies that surrounded it. And even with Egypt's censorship measures in place protesters were still able to use Twitter to coordinate their movements by using standard dial-up connections. Similar controls also failed in Tunisia, a country that also has strong censorship measures in place. People were able to create their own private URL in order to bypass Tunisia’s internet server. These realities at the very least cast doubt on the assertion that the internet can be easily controlled even in times of crisis.