Subsections

Qualitative UX Research Methods

This IRB-approved study took place using Zoom online conferencing software to meet with TPC stakeholders from colleges and universities in the United States of America. Though originally planned to capture experience of faculty and students, only ten faculty participants of various ranks and positions participated in the qualitative interviews. All interviews took place between March 1st, 2021 and May 30th, 2021. During the interviews, faculty explored their experiences in the classroom since the start of the pandemic. All participants responded orally to questions about changes to their teaching, environments, technology, student behavior, and human presence in their classes. Hereafter, I will elaborate briefly on recruitment, participants, data collection, data analysis, and data security methods used during the study.

Recruitment

In preparation for recruitment, and based on guidance from the Office of Research Compliance, eligibility requirements and solicitation methods were developed. TPC stakeholders were identified as the study group for this project because of the field’s rapidly growing digital footprint, its definitional focus on communication technology, its current call for covid pedagogy research, and its relationship to the primary investigator’s position. Therefore, participants had to be faculty and/or student stakeholders in Technical and Professional Communication courses that took place before, during, and after the start of the pandemic. For comparison purposes, faculty participants had to have prior experience teaching courses before the pandemic impacted their classrooms and pedagogy. Additionally, all participants had to be over 18 years of age and not a member of a protected group of human subjects identified by the OHRP (Office of Human Research Protections, 2021). These factors informed participant solicitation.

Solicitation of participants for the study leveraged three venues and used three methods. First, potential faculty and student participants were contacted via an email recruiting initiative. This method involved contacting TPC faculty at various institutions and then having them forward the message to students in their respective, relevant courses. Second, potential faculty and student participants were recruited via a similar research message posted on both the Association of Teachers of Technical Writing (ATTW) and the Society for Technical Communication (STC) online message boards and listserv services. Third, potential faculty and student participants were recruited via in-class visits conducted by myself where the project could be defined, informed consent explained, and participation requested. Out of all venues and methods, all ten faculty participants were acquired using electronic messaging (email and/or listservs) and they self-selected to participate based on interest in the study. No students were successfully recruited to participate.

Participants

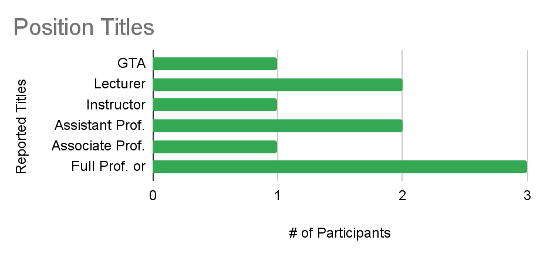

All ten faculty participants in my case study completed demographic surveys prior to the interview process. Based on survey response data, all participants identified as TPC faculty of various rank and experience in the field. In Figure 1 (below) I provide rank and experience data based on self-described position information.

Figure 1.

Faculty Participant Position Titles

Note: The horizontal bar chart shows reported titles of ten faculty participants in the case study based on their demographic surveys.

According to the survey, the majority of TPC faculty participants were in tenure eligible positions (N=6, 60%). Non tenure eligible faculty positions accounted for the second most represented group of participants (N=3, 30%). Graduate teaching assistants were also represented in the pool, but via only one 5th year PhD program participant (N=1, 10%). This indicates that most participants in the case study either have or are tenure eligible and can offer reasonable experience teaching TPC. That is, since they report having taught the full course both before and after the start of the pandemic, even the least experienced among them must have a minimum of 18-30 months experience teaching in TPC at the time of this study.

Further, participant survey data reveals that they not only represent a wide array of ranks and experiences, but they also represent a diverse age range and gender identification. The average age of participants was 43.375, with a median age of 38.5. The youngest participant was 28 and the oldest was 71. The majority of participants were between the ages of 30-39 (N=4). Thus, the majority of participants were in their early to middle career stream. Also, of the ten participants, five identified as female, four as male, and one participant did not indicate a gender preference. Therefore, both masculine and feminine gender identities were mostly balanced in their representation, but non-gender conforming individuals may be underrepresented. With this pool of participants, I began data collection.

Data Collection

Once all participants’ eligibility was confirmed, I collected informed consent and pre-interview surveys. I used remote, qualitative interview methods for data collection. The Zoom interview process involved intense, semi-structured question and answer sessions (Charmaz, 2006). Semi-structured interviews were chosen because the method generates rich, exploratory data, and allows the researcher to get “accurate information” and to learn from the “participant’s experiences and reflections” (p. 26). During sessions, I worked to create a comfortable and familiar environment. Then, I elicited faculty participants' responses to their pre-and-post pandemic TPC classroom pedagogy, environment, technology, student learning, and personal teaching experiences using open-ended questions (see Appendix A). Being able to build camaraderie and to probe faculty practices, feelings, and insights helped to deepen my understanding of my fellow TPC stakeholders’ perspectives in the current educational environment.

Regarding interview logistical details, all remote interviews took place online via Zoom. They were scheduled during March, April, and May of 2021 at the convenience of the participant. Invitations and arrangements were made by myself and accomodations were made for participants who needed to either reschedule or acquire assistive technologies for online support. All interviews were audio and video captured, as well as machine transcribed, by the Zoom software. Each interview lasted between 28 minutes and 1 hour and 45 minutes with an average time of 55 minutes and 14 seconds. Each interview transcript was then cleaned using a combination of Atom raw text editing software and manual editing via line-by-line review in MS Word. The time I spent reviewing the videos and correcting transcripts gave me an intimate understanding of participants' expression of perspectives within the study. Further, grounding myself in participants’ critical reflections and thoughtful utterances provided me access to their invaluable experiential data, data only those involved in teaching TPC in the current pandemic era can offer for analysis.

Data Analysis

To analyze the results of my study interviews, I used a combination of a grounded theory approach and thematic analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 1990; Boje, 2001). The line-by-line open coding of the grounded method allows my TPC participants' experiences to reveal their answers to my research questions. And, the approach allows me to discover those answers that directly respond to TPC stakeholders and their situations as they were represented by my participants. Additionally, the grounded approach provided me with personal distance from my experiences, helping to remove my opinions as a member of the target population for this study.

As for thematic analysis, the line-by-line open coding empowered me to find shared ideas and concepts in the responses of my TPC participants. Developing and using a codebook with key definitions and examples from the data, I was able to categorize, compare, and interpret participant utterances. Then I grouped similar responses to my inquiries, and studied insights into how the pandemic changed TPC instruction regarding privacy and presence in the classroom environment. The creation of holistic themes around these topics, “an act of co-construction…between [participants] many stories,” shaped the answers to my research questions and how we might balance privacy concerns with the need for presence in pedagogy of the pandemic era (Boje, 2001, p. 135). The themes of uncertainty in computer-aided pedagogy, troubled technological solutions, privacy erosion, environmental facturing, and the power of professional and personal presence, bring participants’ concerns to the fore and help us develop informed responses to our new TPC normal in digitized spaces.

Returning to my relationship to the participants in this case study, I must offer that my own experiences may shape some of my interpretations. However, these experiences are relevant to this study and provide my work with increased potential and interpretive value. I am a TPC educator who, like my participants, has taught courses both pre-and-post pandemic. Additionally, as a qualitative researcher I am well aware of myself-as-research-instrument and the impact that may have on data analysis, but also the value that may bring (Tracy, 2020). The affordances and limitations of which I will redress in the conclusion of this report.

Data Security

For data collection, reporting, and analysis no names were recorded as part of the study data. Instead, all participants were randomly assigned a pseudonym. Realistic pseudonyms were used to create a human connection with participants. They do not represent the gender identity of a participant. Further, pseudonyms were used on all collection and analysis documents, as well as within the report. Actual names were only used on the sign-up sheet, in correspondence, and for informed consent. All individual and institutional information is and shall remain anonymous and separate from the demographic survey and interview data. All demographic surveys were aggregated when used in this report. Any names of people, places, and/or things mentioned in the data were omitted in the results and discussion sections. Random pseudonyms and data removal disables indirect identification. All pseudonyms, abstracted locations, or other potentially identifiable institution, program, or named information has been altered to protect participant identity and to conceal affiliations and locations.