Moving Images of Literacy

in a Transnational World

By Gail Hawisher, Patrick W. Berry, Hannah Lee, and Synne Skjulstad

Listening to and viewing Sondra’s remarkable presentation on digital story-telling, I’m reminded of the telling connections between our pedagogy and research. This morning, I’d like to talk about the connections I’ve tried to make in moving from pedagogical approaches that rely on digital media to a digitally-informed research methodology for capturing some of the nuances of literate practices here and abroad. I also present some video work by coauthors, Synne Skjulstad, of Oslo, Norway, and Hannah Kyung Lee, of Chicago, Illinois. (Image)

As some of you know, Cynthia Selfe and I have long been involved in studying how people take up digital tools as students, as writers, as professionals, and increasingly simply as human beings, here and abroad, going about their everyday activities in a world richly saturated with digital communication technologies (Appadurai). We have focused this work on literacy narratives from within the United States but have also—since the publication of Literate Lives in the Information Age—paid a great deal of attention to transnational contexts and to those who claim transnational identities. In fact, joined by Patrick Berry, we have just submitted a prospectus to Computers and Composition Digital Press (CCDP) proposing a book-length text entitled Transnational Literate Lives. (Image) The book features videotaped life history interviews that we conducted with undergraduates in Sydney, Australia; literacy narratives with undergraduates from Nigeria and China; as well as writing process videos from transnationally-connected graduate students in Urbana, Illinois.

(Image) With this term transnational, we intend to signal those of us who are at home in more than one culture and whose identities, as Wan Shun Eva Lam (2004) notes, are “spread over multiple geographic territories” (p. 79). Often those who claim a transnational identity speak multiple languages, including variations of World Englishes; and maintain rich active networks of friends, family members, and contacts around the globe.

This morning I attempt to trace how—and also why—the research methodologies we’ve deployed in carrying out these studies have evolved in the ways that they have and show you videos that have emerged from the study. In making these strategic research moves, we’ve become evermore aware, as Wendy Hesford points out, (Image) of “the methodological challenges we face as we turn toward the global” (p. 788) and how, as Hesford also suggests, the global turn demands critical literacies that connect up with responsibilities of a global citizenship. My coauthors for the talk this morning are Cindy, Patrick, Hannah Lee, and Synne Skjulstad.

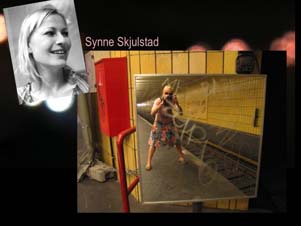

(Image) I begin with Synne Skjulstad, now a postdoctoral researcher in the Institute of Media and Communication at the University of Oslo, who was very influential in helping us see the benefits that might accrue from using digital media not only as research tools but also as providing sites through which to present research. Some of you have heard me say that Synne not only suggested the Web as a research venue but implied that we really couldn’t present our research adequately in print; that our current research in Literate Lives at the time lacked the richness that video clips might provide; and, finally, that if we were going to study digital contexts in the 21st century how could we possibly not use digital tools for the research.

And, frankly, we discovered that her arguments held a great deal of weight in our experience of publishing recently in print venues. A good example is a chapter we did for Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis’s new book on Ubiquitous Learning (Image), which we couldn’t have been more pleased to be a part of but worried about our now print-rendered videos. In this effort to represent the videos in print, coauthors Patrick Berry and Janine Solberg crafted film strips of the video clips creating beautifully rendered illustrations to try to address the problems.

Here’s what we wrote in attempting to explain why our contribution, “Ubiquitous Writing and Learning,” (Image) wasn’t able to convey the full meaning we intended despite our being delighted with the chapter and the book:

Digital video representation easily foregrounds what print seems to easily elide, that writing is embodied-activity-in-the-world, that it is consciousness in action, that it is saturated with affect and identity, that it is social as writers interact with others (people, sometimes animals, and even things).” (Hawisher, Prior, Berry, Buck, Gump, Holding, Olson, Lee, Solberg, 2009, pp. 260-261)

That’s not to say that print doesn’t provide affordances that video clips and other media seem themselves to elide. In preparing the Computers and Composition Digital Press manuscript and prospectus I mentioned at the start, we learned that some of what we regarded as our best theoretical arguments seemed to get short shrift in the digital multimodal environment. Extended text on the screen doesn’t always attract the close reading that academe often prizes. The point here, I think, is that we need to examine with care the genres and the circumstances that each multimodal genre or each mode of presentation makes possible (Prior, Porter). (Image)

Let me turn now to some of the adjustments we made in methodology with Synne herself as participant and coauthor. Through this collaboration with Synne, we learned the value of collecting multiple media for our research, including alphabetic text and, this morning, I attempt to show you how we’ve tried to craft a method that draws on all available means—or at least taken steps in that direction.

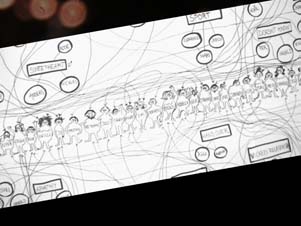

Synne, like some of the other research participants, completed an online literacy autobiography, which, in Synne’s hands, turned out to be 66 pages interspersed with images of herself, her life, and her writing and computing experiences. (Image)

She also shot footage of her typical Norwegian day in Oslo saturated, we would argue, with activity that connects up with her literate life. Unlike other participants (Image), Synne had embedded photos that demonstrate how visual components can inform narrative (Image), along with aesthetically composed video footage (Video). It’s noteworthy too that even as a young student, whenever possible, Synne turned to images and multimodal representation rather than relying primarily on words, and this penchant of hers—this literacy practice—continues to this day.

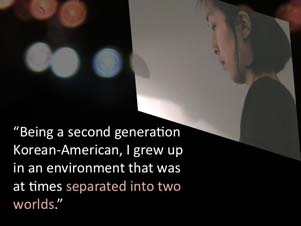

I’d now like to demonstrate how I’ve tried to incorporate this methodology into my own teaching and research, and here introduce another coauthor, Hannah Lee (Image), who, like Synne, was born in the country in which she’s spent her entire life, but who nevertheless claims a transnational identity with her family origins in Korea.

As Hannah herself explains about her life as a Korean and as an American,

(Image) Being a second generation Korean-American, I grew up in an environment that was at times separated into two worlds.

(Image) My “inner” world consisted of home and family—the Korean side of me. Here, I spoke mostly Korean and some English with my parents. On Saturdays, I would attend Niles Korean School and learn the basics of reading and writing in Korean.

(Image) My “outer” world consisted of school, the rest of society, and speaking English. Most of the time these two worlds remained separate, but every once in a while one would merge into the other.

Hannah Lee was born seven years later than Synne on August 27, 1980 in Chicago and grew up primarily in an area called Rogers Park (Image), a community known for its diversity then and now. Hannah tells us that she grew up in a language-rich environment and often heard languages such as Spanish, Polish, and Hindi, along with other Indian languages.

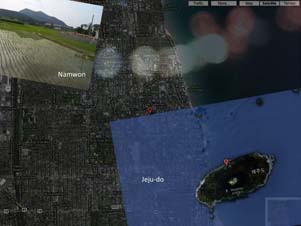

(Image) Both her parents were born in Korea—her father on the island Jeju-do, which is a volcanic island and now a UNESCO World Heritage site—and her mother in Namwon, where she grew up on a farm. Her parents came to the United States, separately, not long before Hannah was born, with her mother working as a nurse and her father eventually going on to own his own architectural firm. (Image) Going to his office provided opportunities for Hannah and her sister as children to experiment with various computer applications including word processing, software packages that vendors would send her father, and America Online. She remembers in the early 1990s discovering chat rooms with her sister and having conversations with people from all over the United States.

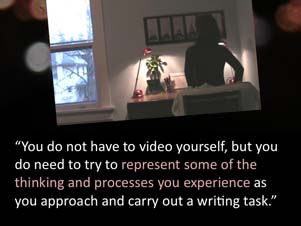

In 2006 (Image), Hannah entered the MA writing studies graduate program at Illinois, enrolled in my graduate seminar, and, as part of that class completed what I’ve called a writing process video. The assignment asked that students attempt to capture a representation of their processes on camera and explained: (Image)

You do not have to video yourself, but you do need to try to represent some of the thinking and processes you experience as you approach and carry out a writing task.

Here is the video that Hannah composed: (Video)

In writing about her video, Hannah says, (Image)

My video camera went with me wherever I went—the bus, the airport, my apartment, my mother’s house. I knew that I wanted to collect a montage of my daily activities, to translate these images, sounds, and words into something that would portray the mundane, yet mind-wrenching activity that is my writing process.

She adds,

Notions of stretched and retracted time were invoked. (Image) Time seemed to pass by without my noticing as I worked on the video—which is nothing like the dread and procrastination that usually accompanies my typical writing assignments with their ever-present deadlines looming before me. The hours it took to get the various shots of me typing at my computer amount to a few moments in the video. Yet the repetitive, insistent cuts evoke the feeling of stretched time. (Image) Quickly paced cuts of the activities that I engage in while not writing—checking my email, going for a walk, getting a drink of water—push their way into my writing process and keep me from it, all the while engaging with it, briskly furthering the process along.

In many respects, Hannah’s video begins to illustrate what Elaine Chin has written about writing and its production. Chin argues (Image)

The context for the production of writing always includes the material conditions, the time and space writers occupy as they write, as well as the web of social interactions affecting composing. But more importantly, the context for the production of writing needs to be conceptualized as the writer in situ in that it is the social text that writers create for themselves and in which they situate themselves. (Elaine Chin, pp. 476-477)

And here, with the video, it is Hannah doing the conceptualization, not necessarily a researcher looking on. What we perhaps see less of in this particular video of Hannah’s are ostensible traces of how family histories and cultural customs are folded into her everyday literacies. Without more background of her literate life and of what Cindy and I have called the cultural ecology of digital literacies, lots is elided in Hannah’s rich story of her literate activity (Prior).

But through online alphabetic writing, Hannah has told us something additional about the joys of transnational ties—visiting family in Korea—but also of the difficulties of being a second-generation American and its impact on language and communication. She writes

I never really thought about the communication barriers I’ve had to grow up with until I took my second trip to Korea (I’ve been to Korea three times so far). (Image) In many ways it felt good to go back to my roots. Yet, as I visited cousins and aunts and uncles and grandparents that I never knew, and tried to communicate with them in the Korean that I had managed not to forget over the years (Image) I noticed for the first time just how different my experiences were from those of my cousins. I marveled at how easily they communicated with my aunts and uncles and how perfectly they understood each another. My cousins didn’t have to tone down or change their words so that their parents could understand. They simply spoke.

And Hannah has said more. She has noted, for example, that communicating with her mother in this country is also sometimes a challenge. When Hannah related her literacy narrative through the DALN, the Digital Archives of Literacy Narratives that Cindy and Louie Ulman have established at Ohio State, she elaborated on issues of communicating, only this time here in the United States with her mother: (Video)

(Image) Here Hannah describes her role as a translator—as a mediator—in helping her mother negotiate day-to-day literacies in an environment where some make the mistake of thinking her mother uneducated because they themselves don’t recognize her fluency and expertise in Korean—a language in which she writes poems and essays that they cannot understand. Hannah reminds us too that while those with transnational connections tell of shared experiences—problems with communication, for example—that there are also complexities—her mother’s hearing loss—that amplify the individual problems at hand.

(Video) In my talk this morning, I have done justice neither to Hannah and her literate life, nor to her aesthetic storytelling. That’s for another talk—for another chapter in Transnational Literate Lives. But her literacy narrative and video begin to speak to how we constitute literate identities and perhaps to how as teacher-scholars in writing studies—or digital writing studies as Cheryl Ball has named us—we might go about our research. At the very least, I hope I have begun to illustrate a research approach that can help us better understand how personal and cultural histories shape people’s literate practices and how digital tools can help us in that effort.