Stories That Speak To Us:

Multimodal Literacy Narratives

By Cynthia Selfe

As you’ve heard, Sondra and Gail have spoken about the aesthetics of digital narratives and the use of digital narratives as a research methodology.

But, for the next few minutes, I’d like to discuss two particular ways of analyzing narratives for what they can tell us about individuals’ representations of themselves and others as literate beings, and for clues about how literacy practices and values have shaped their lives.

For this work, I‘ll draw on narrative theory and techniques of narrative analysis. (Image)

I locate my interest in stories within the context of a “third wave” of narrative studies that has extended across the fields of education, sociolinguistics, linguistic anthropology, discourse analysis, social psychology, folklore, history, literature, and a number of other disciplines.

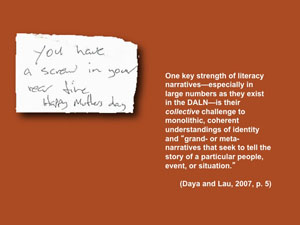

This new landscape of narrative studies shifts our focus from what used to be a fascination with the structure and the analysis of personal stories to a focus on how such accounts are tied in fundamental ways to culture, meaning, knowledge, identity formation and transformation in all human beings. (Image)

Now, how does this third wave of narrative studies play itself out within college-level composition classrooms?

Certainly, over the past two decades, it’s become a common place for both teachers and literacy scholars to note that we can understand reading and composing as a set of practices and values only when we properly situate these within the context of a particular historical period, a specific cultural milieu, a cluster of actual material conditions, and the complex and situated lives and experiences of real students and their families (Street,1995; Gee, 1996; Graff, 1987; Brandt, 1995, 1998, 1999, 2001).

And so, we’ve seen increasing numbers of teachers and scholars, operating from such an understanding, turn to personal narratives as an effective way of exploring the social, cultural, political, ideological, and historical formations that have shaped the literacy practices and values of people and groups—Mike Rose, Anne Gere, Jackie Jones Royster, Shirley Brice Heath, and Deborah Brandt, have produced some of the best known examples of this work. (Image)

For faculty who teach composition, however, such contextual information may be difficult and time consuming to come by.

Perhaps even more important, our own professional commitment to equity and fairness, nested in the common belief that the composition classroom should provide a level playing field for all students’ accomplishments, often encourages us to underplay the importance of students’ personal backgrounds---even, as Bruce Horner has observed, to objectify students as interchangeable learning subjects, as if they come to us without context, without histories, without culture, and without their own personal narratives.

This is not to say that we don’t care about students, we do; we just don’t always know them.

We don’t always know what literacy experiences they bring to the classroom; we don’t know how or why they learn best; we don’t always know what identities they have forged for themselves as literate individuals, and we don’t know how these identities might affect the instruction we provide. (Image)

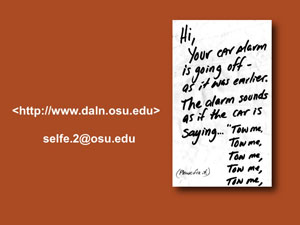

The narratives I’ll use in this talk come from the Digital Archives of Literacy Narratives, the DALN, a publicly available archive of autobiographical recollections of how individuals learn to read and write; the conditions under which they continue do so; and the influences and values that shape their literate practices.

The DALN features these first-hand accounts in a web-based site that any citizen or scholar can use. People can contribute their own stories for their own purposes form home, or, like many of us, they can use the Archive to do their own primary research, to identify and study emerging literacy trends or trace literacy practices and values in a contemporary, historical, or cultural context. (Image)

In particular, today, I want to suggest that the literacy narratives in the DALN can help composition faculty and students extend their understanding in two important areas:

First these narratives can help us can help us understand how identity formation and transformation takes place within the social contexts surrounding literacy practices; (Image)

Second, the DALN narratives can help us understand the social and political agency that individuals enact through literacy and their stories about literacy. (Image)

I’ll start with identity formation.

Most narrative scholars agree that stories, even small stories, can be understood as providing powerful discursive vehicles for the formation of identity and self representation.

The map of an individual’s attempt to become a certain kind of person, as Kraus (2006) notes is both “socially embedded, and readable” in the narratives they tell (p. 106).

In addition, because such stories focus on events that happen over time, they often reflect the fluid and multiple nature of personal identity: how individuals feel they have have changed; the different and multiple subject positions they feel they have inhabited in school, at home, in church, and in peer groups; and the trajectories they have established for their own lives leading into the future. (Image)

Perhaps one of the most important aspects of identity formation in narratives, as Stan Wortham points out,

…is that “Telling a story about oneself can sometimes transform that self…Sometimes narrators…change who they are, in part, by telling stories about themselves” (p. 157).

Now, exactly how are such identity transformations effected?

Scholars offer differing explanations. Wortham (2000), for example, focuses on the performative aspects of identity, suggesting that

“While telling their stories, autobiographical narrators often enact a characteristic type of self, and through repeated performances of this kind, they may in part become that type of self” (p. 158).

In such performances of identity, individuals construct their identities, in part, through selection: choosing “stories to tell (or not to tell) and details to represent (or not represent).” They describe themselves and others in a certain way and, thus, “reinforce (or ignore) certain characteristics” (Wortham, p. 158) of their personality or foreground “one particular description, despite many other possibilities” (p. 164). (Image)

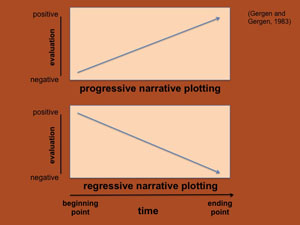

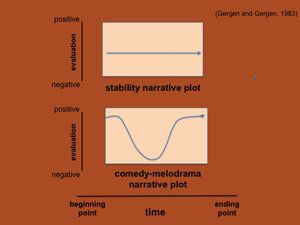

Other psychologists, like Mary and Kenneth Gergen (1983, 1988) and narrative theorists like Anthony Kerby (1991) suggest that it is the act plotting personal narratives, that represents a key to their transformative power.

We plot, these scholars suggest, “who we want to be and become.”

As Gergen and Gergen (1988) explain, in telling a story, people often identify both a beginning point of the experience they want to relate and a “valued end point” or “goal state” (p. 21) of their experience.

Then, as individuals tell their story, they select the specific events that form an inferential trail between these two points, creating—in the selection of these details—the plot line or the desired trajectory of the teller’s life. (Image)

Narrative plots, then, have not only descriptive but also predictive, or transformative, power. They plot, as Kerby maintains (1991, p. 54), not only who we think we are, but also “who we may become”. Gergen and Gergan identify a series of typical plots lines that individuals use to structure their stories and their lives: a progressive narrative with a rising line, a regressive narrative with a downward trend, a stable narrative suggesting little change , or an uncertain plot line that suggests continued ups and downs.(Image)

As an example, of this last point, I’d like to show you a narrative recently submitted to the DALN by John McBrayer, a 21 year old comic artist, a lover of books, and a future teacher of English.

In this personal literacy account, which takes the form of a comic book, John tells us what Mary and Kenneth Gergen call a progressive narrative, plotting his life story along a rising line. (Image)

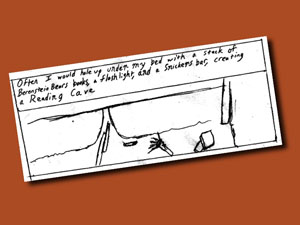

In this first panel of his narrative, John begins his story by establishing his own early love of reading which, as you can see, starts with his childhood habit of reading, under his bed, with a flashlight, nibbling on a Snickers bar. (Image)

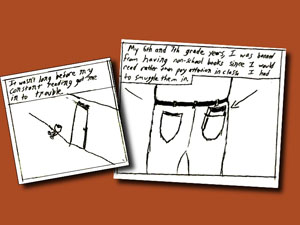

John continues his story by selecting a detail from his 6th and 7th grade experiences.

In this panel, he tells how he smuggled non-school books into his classes so that he could read while the teacher droned on, rather than “paying attention” to instruction that he found less than engaging. (Image)

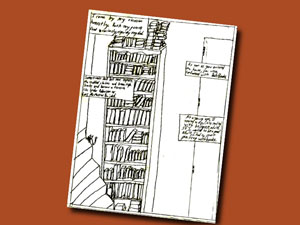

In this panel, John punctuates his story by mentioning his many marvelous forays into his father’s library, which you can see represented here, from which he is allowed to borrow and read all sorts of books.

These are opportunities, John tell us, that he remembers with great fondness. (Image)

It is important to note that John’s narrative shows all the signs of being a predictive representation as well as a descriptive one.

It’s plot line, in addition to pointing him, in the near future, toward graduation from a teacher education program, also clearly reveals the longer-term goals that drive his efforts toward a “valued end point” of becoming the kind of teacher who helps youngsters discover the joys of reading, and who has a “mindblowing,” one-to-many effect that helps him transform them into book lovers as well. (Image)

As John’s narrative illustrates, the stories in the DALN can also carry extensive information about familial material conditiosn, through anecdotes about home life; about literacy values and concerns, though details about reading or writing habits or the expectations of parents and peers; and about historical era, through clothing, slang, and reference to popular culture; and about education, through individuals’ diction, vocabulary, and personal details about instructional experiences.

The stories also, however, reveal a great deal about social and political affiliations through the inclusion of other people and groups as characters in the stories individuals tell and the tellers’ relational identifications with these characters.

And it is this concept of relational identification or relational positioning that I’d like to explore as a second major concept that can be used to analyze literacy narratives in productive ways.

Narratives because they are always embedded in, and illustrative of, the social systems within which their tellers live, provide a space in which individuals articulate their identifications with—or in resistance to—specific people and groups. (Image)

By locating themselves precisely and in nuanced ways within complex and dynamic social systems in their narratives, as Buckholz and Hall suggest, storytellers, actually compose their lives and values in reference to those around them, positioning themselves relationally to the other characters in their stories, to their previous selves, and to their listening audiences.

Thus, story tellers situate themselves—both in positive and resistant ways—to parents and other family members who them help establish personal literacy values; to sponsors (using Deborah Brandt’s term) who provide entrés and support for particular literate activities; to teachers who might punish, reward, or control their practices as readers and writers; and to peers who might share or resist a storyteller’s personal literacy values. (Video)

And that brings us to Deqa Muhammed, another recent contributor to the DALN, who immigrated to this country in 1996, with her mother and brother, fleeing Somalia and the longstanding war that ravaged her country.

In this edited clip, Deqa tells the story of her mother’s struggle to learn English and provides some advice for others who are finding it difficult to read and write—either in their first language or in a second language. (Image)

Now, as you’ve heard, Deqa’s narrative, like John’s follows a progressive plot line that starts with her family’s immigration; traces their struggles as new immigrants and language learners; and ends with her mother’s learning to speak English, her younger brother’s learning to read, and her own claim that everyone can learn to read and write if they work hard enough.

The relational positioning in Deqa’s story, I think, is also worth a closer look because it is so complex.

In this short clip, Deqa positions herself in several ways: first, of course, she aligns herself strongly with her family and their struggles as immigrants new to the U.S. She tells about her mother’s struggles with obvious pride, noting how both she and her brother offered late night ESL classes at the kitchen table, how her mother worked hard both on her own, and later in school with the “older women,” to learn English.(Image)

But Deqa also distances and distinguishes her story from that of her mother, identifying her as a member of a different generation. She notes, for instance, that she and her brother learned English more quickly than their mom given their ages, that they found it easier to develop fluency in the language, and that they managed to lose the accent that their mother retains.

Through these details of her story, in short, Deqa positions herself—in terms of her dress, her accent, her use of English idiom, her narrative itself—as a second generation citizen of the U.S., a person from Somalia, but also a person who fits right into an American context because she has worked hard to acquire a set of language skills.

Her telling lends important nuance to this position near the end of her story, however, when she also situates herself in direct opposition to intolerant native citizens of the U.S. who make “ignorant comments,” “If you don’t know English go back to your own country.” (Image)

In a story like Deqa’s, I would contend, an individual’s relational positioning vis a vis their own and others’ literacy practices and values is not simply a detail within their narrative but, rather, a specific form of personal and political rhetorical agency.

People often tell the narratives they do to make a point and to persuade—and, in these instances, stories themselves become a form of political action, a form of “doing,” not simply a simple tale that is told by one person and heard by others.

Deqa’s narrative, in sum, positions her against intolerance and in solidarity with hard work. She tells her story as a way of taking action against xenophpbia and encouraging others to see her family not as a problem, but an inspiration for all people struggling to learn how to read and write.

Her story ends with a challenge, “If my five year old cousin can establish himself in terms of writing and reading then anyone can do it. And if my mom can do it—who didn’t speak the language at all and who is an older lady who took forever to learn—then anyone can. And I leave you with that.” (Image)

It is true, of course, that any one interpretation of a literacy narrative is necessarily partial and incomplete, “emergent, unpredictable, and unfinished,” as Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 479) would say. Each story I’ve shown to you is, after all, selected for telling to others and is, what Dava and Lau (p. 2) note only “a glittering fragment” of what people think of as reality. (Image)

I’ll close by noting that stories really can speak to us: about the lives of students, about their literacy values and beliefs, and about the different kinds of literate identities and literacy practices they bring to our classrooms.

Such narratives, in addition, can do powerful work for students by providing them discursive spaces for dynamically constructing and reconstructing their literate identities in light of the worlds they inhabit at home and the worlds they encounter in our classrooms.

And so I’ll invite all of you in the audience to become a Contributing Partner with the DALN by designating a day or an hour during which you collect literacy narratives in your own classrooms or reading rooms and inviting students to contribute them to the DALN so that we’ll all learn from them. Or by contributing your own story at out “Every CCCC Member has a Literacy Story” table near the exhibit area of this conference. Currently, the DALN has preserved more than 1200 such narratives, and we hope to collect many more during these three days of the 4 CCCCs.

If we ask students to tell us about their literate lives, and if we listen carefully, if we pay attention, we will approach them not as interchangeable learning subjects, but rather as individuals, each of whom brings a radically different background and a different set literacy experiences to bear on the tasks we ask them to accomplish.

The insights and respect that can accrue from this work of individual recognition and respect, I am certain, can help us make them better scholars and ourselves better teachers.