The Instructor’s Perspective: A View

from the Top

|

|

"We all led fictional

lives in the very moments we faced one another, even when the presence

of the others who remained out of sight was only imagined."

Dan Rose, 1987

Black American Street Life

|

The

Questions

When

Dan Rose says that we all lead fictional lives, he is alluding to both the

primary difficulty in traditional ethnography and the primary strength of

postmodern ethnography. If identity is this slippery thing, if it is

always already a performance, as Judith Butler would say, then those

multiple performances don't undermine the real. They are the real --

fragmented, slippery, constantly shifting.

I could hardly be

labeled "queer" under traditional methods of categorization – where queer

is viewed in opposition to normal, much as gay is viewed in opposition

to straight. I am an Anglo heterosexual male from a Southern U.S.,

middle-class suburban background, fast approaching middle-age. I’ve

assimilated to American Broadcast English, having erased, as best as I

can, all traces of a Southern drawl during my 15 year transplantation to

New England and then to the Midwest. I live with my wife and son in an

economical condominium in a traditional, upper-middle-class neighborhood

and commute in a mid-priced sedan to my job as a tenure-track college

professor. While my material body may be marked by a few small signs of

Otherness (a few piercings, a tattoo, Doc Martins), and my virtual body

may be marked by expressions of subaltern politics and queer theory, I

perform in the classroom with the inescapable authority of white male heterosexual

middle-class privilege.

As a college professor of e-composition

in suburban Detroit, I inevitably build

my courses

around issues of diversity and Otherness. Students are asked to read about

issues involving relations of race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and

other markers of difference and Otherness. They are asked to explore their

own communities and share their own experiences about encountering

difference or representing Otherness.

This

schism between privilege and pedagogy creates an inevitable contradiction

in the classroom. How can I justify inviting students into open dialogue

about difference from my own safe position of privilege? Then again, how

"safe" is my position, in a context where I advocate that race, gender,

and sexual orientation are social constructions?

This narrative

describes my own participation in a larger project about the transgendered and transgressive student in the writing classroom -- as a

mentor for Lindsey who embarked on

her own reflexive examination of transgendered identity. As the

instructor, what are my own concerns about ethics and auto-ethnography?

About the risks of reflexive writing? About gender identity, sexual

politics, and concern for the welfare of students who walk that thin

line between hazardous visibility and silent safety. As Michael Bronski (1998) points

out, "The line between perceived tolerance and incipient violence [is]

often shifting, and the need to be mindful of the code [is] important. To

overstep or misperceive the line could lead to harassment or physical

attack" (p. 55). What are my own ethical obligations when students engage

in and share self-reflexive research on sexual identity that transgresses

community norms?

Return to Top

Background

For the Winter of

2002, as a relatively new tenure-track faculty member at Oakland

University in Rochester, Michigan, I was asked to teach a newly developed,

upper-level course in Rhetoric titled "Advanced Writing: Ethnography."

This would be the first time the course had run, having recently been

approved by the university’s Committee on Instruction. The university

catalogue describes the course as "development of analytic and

collaborative writing skills in the context of ethnographic study –

analytical description and examination of a cultural setting, a

subculture, or a cultural event."

I would emphasize in this particular

course the ethnographic notion of subverting what is normal by "making the

strange familiar and the familiar strange" in an attempt to show students

the relationship between perspective, knowledge, and judgment.

In my

own background, ethnography had been a steadily growing interest since my

experiences after my B.A. as a teacher in a psychiatric hospital and as a

juvenile probation officer in Louisiana -- both being experiences that

raised concerns for me over power dynamics among individuals within

institutional settings and the influences of such differences as race and

class, for example, on those dynamics. My training and background in

ethnography came through the field of composition and literacy studies,

which can be quite a bit less formal (and rely less on strict coding and

quantitative analysis) than in sociology and anthropology and much less

structured than ethno-methodology and conversational analysis.

I had

recently completed my Ph.D. at Wayne State University in Detroit on

Literacy, Technology, and Justice in Postindustrial Detroit -- a rather

grand title for a project much narrower in scope than the title implies.

My dissertation involved self-reflexive educational ethnography

(participant-observation research in the computer classroom and at a local

senior citizen community center); observations, interviews, and surveys

concerning student experiences with and attitudes toward computers and the

Internet; and pilot classroom projects that asked students to employ

ethnographic research strategies to provide multi-vocal accounts of

Detroit's local and historical cultures. These projects relied heavily on

interviews and oral histories and involved building web sites to archive

their work.

In my

teaching, I focused on the ways in which principles of ethnographic

research can provide students with sophisticated writing and reasoning

strategies -- introducing students to basic principles of ethnographic

fieldwork and leading them into research and writing projects in which

they put some of those principles into practice by investigating specific

sites for such issues as negotiations of power, symbolic meaning, social

construction of group identity or member roles, or a combination of those

issues.

Because of my own

interests in technology, the ethnography course I was asked to teach at

Oakland was designated as a computer intensive course, meeting in a

computer classroom and utilizing WebCT, email, and the web. During the

first half of the semester, we would

discuss ethnographic inquiry

as a

research methodology, examine various contemporary ethnographies, and

engage in online writing assignments, including a review of a published

ethnographic study and their own mini-ethnographic projects. Students

would post ideas and responses to the readings to the class discussion

board and ideally read each others’ posts. During the second half of the

project, each student would design his or her own ethnographic project and

execute it in multiple stages -- a literature review, a proposal for IRB

approval, a site study, field observations, interviews/case studies, an

ethnographic essay, and a self-reflection, much of which would also be

posted to the discussion board. Students were also offered the option of

converting their final projects to web sites.

The

role of technology in the course was to bring the different perspectives

and experiences into contact with each other, allowing them to reflect on

and respond to each others virtual bodies of evidence and reflection. We

used WebCT to establish a mailing list and resource archive, but also

created a discussion board for student reflections, and a Reading Notebook

for each student in which they posted reading reflections and field notes.

We

used WebCT to establish a mailing list and resource archive, but also

created a discussion board for student reflections, and a Reading Notebook

for each student in which they posted reading reflections and field notes.

I didn’t expect

most students to come in to the course with much exposure to cultural

diversity. Oakland University is a suburban Detroit public university

founded in 1956 that primarily serves students from Oakland County, a

relatively affluent area in Metro-Detroit, recently deemed the most

segregated metropolitan area in the country. Most students are commuters

from their home communities, largely upper-middle class and predominantly

white. Racial demographics for the student population are on par with

national averages (over 80% white and around 12% African American) and

have a slightly higher ratio of females to males (60% female to 40% male).

The university mythology is that affluent Oakland County families sent

their sons off to Ivy League and state universities, and kept their

daughters close to home. The general expectation of faculty for students

is that they are usually homogeneous and inexperienced with alternate

viewpoints. However, I’ve discovered that if you scratch at the surface

some, this isn’t quite the case: many students are 2nd or 3rd

generation Americans, having grandparents who immigrated from Eastern

Europe or the Middle East. Many have languages other than English spoken

in their homes. Though there is a conservative slant among them, their

immigrant and working class heritages offer them avenues to understand

identity politics and social stratification.

Return to Top

The

Semester

In this particular

course, there was very low enrollment for a number of reasons. Only 9

students signed up and 6 finished the course. But beyond the surface-level

"whiteness" of the class, there was quite a bit of diversity. Two students identified as bi-ethnic (Latina and Arabic) and one

other identified as Ukrainian American. One student was a young mother. Lindsey, early in

the course articulated interest in and sympathy with queer culture – from

discussions of Furries (a sexual fetish involving animal role play), to a

review of Laud Humphries’ Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Pubic Places,

to her own auto-ethnography on Drag King culture. However, Lindsey never

expressly out-ed herself as queer or as transgendered or as a lesbian to

the rest of the class, though she did frequently talk about queer culture

and her own project on drag kings, and she did perform as

Luke,

her drag alter-ego, during her presentation of her project at the end of

the semester. Clearly the students had different experiences and

understandings in terms of identity and group affiliation that ruptured

the illusion of homogeneity among them.

One of my goals in

the course was to bring students to a complex understanding of

ethnography, beyond a “study of culture.” In addition to traditional

ethnographic methods,

we would talk about feminist ethnographies vis-à-vis

Margaret Wolf

, postmodern ethnographies, the role of phenomenology in

ethnography, the social construction of identity, poly-vocal texts, and

Mary Louis Pratt’s notion of auto-ethnographic texts, an often

misunderstood label for a particular form of ethnography. Pratt explains

that an ethnographic text is one in which "European metropolitan subjects

represent to themselves their others" – a detached scientist reporting

observations about the exotic Other. The auto-ethnographic text, on the

other hand, isn’t just autobiographical. It’s written from the inside in

response to the colonial ethnography. As she explains, "such texts often

constitute a marginalized group’s point of entry into the dominant

circuits of print culture." This notion of auto-ethnography is similar to

De Castell and Bryson’s call for the queering of ethnography. Indeed, much

of the course revolved around what it means to know reality, around the

tension between empiricism and anti-essentialism and the ways in which

observation is filtered by experience, especially among groups with uneven

dynamics of power. One student, looking stunned one rainy Tuesday morning

after a discussion of

phenomenology, remarked that he felt like he was in

a philosophy class.

, postmodern ethnographies, the role of phenomenology in

ethnography, the social construction of identity, poly-vocal texts, and

Mary Louis Pratt’s notion of auto-ethnographic texts, an often

misunderstood label for a particular form of ethnography. Pratt explains

that an ethnographic text is one in which "European metropolitan subjects

represent to themselves their others" – a detached scientist reporting

observations about the exotic Other. The auto-ethnographic text, on the

other hand, isn’t just autobiographical. It’s written from the inside in

response to the colonial ethnography. As she explains, "such texts often

constitute a marginalized group’s point of entry into the dominant

circuits of print culture." This notion of auto-ethnography is similar to

De Castell and Bryson’s call for the queering of ethnography. Indeed, much

of the course revolved around what it means to know reality, around the

tension between empiricism and anti-essentialism and the ways in which

observation is filtered by experience, especially among groups with uneven

dynamics of power. One student, looking stunned one rainy Tuesday morning

after a discussion of

phenomenology, remarked that he felt like he was in

a philosophy class.

Power

and knowledge played an important role in this course. I focused in many

ways on this tension between insider and outsider knowledge, between etic and emic

perspectives. In his 1957 essay, "A Stereoscopic View of the World," Anthropologist

Kenneth Pike describes etic as outsider and emic as insider. The etic perspective is the perspective of scientific analysis -- the outsider

coming in to observe and analyze with preset criteria. The etic

perspective relies on cross-cultural awareness, the use of classifying

grids, the application of a template to the culture in order to analyze,

evaluate, and critique cultural practices. Its value lies in its

comparative analysis. Its weakness is its distance from the object of

analysis -- its failure to address insider knowledge. The emic

perspective, according to Pike, is "insider knowledge." It's mono-cultural

and structural rather than cross-cultural and typological. Its value is

in its reflexivity, its attention to native understanding and shared

knowledge. According to Pike,

it's not a matter of striking a balance between these two positions, but

of being able to simultaneously hold both positions in order to see stereoscopically. Once students begin to transcribe their data and produce a written

description of the culture, they are forced to position themselves in

relation to the object of study.

In this course, students mainly examined

cultures in which they already participated or in which they had a vested

interest: a young mother focusing on a Montessori classroom; a Latina

student focusing on Fuerza, one of the university's Latin American social

organizations, another student wrote an ethnography of Clutch Cargo's – a

local nightclub. One wrote about the tensions between new Ukrainian

immigrants and more assimilated immigrants at a local Ukrainian cultural

center.

Lindsey early in the semester seemed interested in everything all at once and was

having difficulty focusing on a topic. At one point, she had settled on an

ethnography of "Furries," a fetish group whose sexual practices

involve the incorporation of cartoon characters and stuffed animals. She

said that she knew several members personally and that they met once a

month. She would interview group members and observing group meetings. Lindsey

presented this idea to the class during a fairly informal session in which

we elected to meet over coffee in the student center. Noting slightly

shocked expressions on the faces of a few of the students, this raised one

of my first major ethical questions of the semester. As an instructor

performing multiple positions of power, what are my ethical and academic

and legal responsibilities in a student-centered classroom when one

student proposes a project that transgresses the social and sexual mores

of other students? What is my role and responsibility as facilitator in

that classroom?

This

question seems quite large and complicated, but it's not one that I really

even fully articulated to myself. Of course I was keen on the project.

This is what college research and the college experience is supposed to be

about. As Karen Yescavage and Jonathan Alexander (1997) have pointed out,

the issue of sexual identities is always already present in the classroom,

we only "draw attention to them by commenting on the ways in which

sexuality can be socially constructed" (p. 113). So to me, rather quickly,

I saw myself ethically and academically obligated to support free inquiry

into sexual identity, and in the interest of academic freedom regarded

this to be within legal guidelines. Since this time, I have known of at

least one instructor to be accused of sexual harassment by a straight

student for allowing an online discussion of BDSM to go unchecked. A formal complaint was filed,

but it was investigated and found

unsubstantiated since the discussion occurred in the spirit of academic

inquiry. So while it may be politically problematic to facilitate, the

legal, ethical, and academic issues, in my opinion, are much more

supportive of inquiry.

My

decision to support Lindsey's choice of research was much more an innate

position than a conscious deliberation. So when later in the

semester she decided to refocus on transgendered issues, and drag king

culture in particular, I was equally supportive. I did stress, how

ever, the students' own ethical obligations as researchers. In class, we

discussed the

Belmont Report, the American Anthropological Association's "Code

of Ethics," notions of informed consent, and the tension between

risks and benefits in research, including social/psychological risks. My

advice to Lindsey and the others was "be careful." I asked them to think

about potential risks of exposure as carefully as possible, including

self-exposure.

Lindsey and I talked on a number of occasions about

possible consequences of out-ing others or herself. And Lindsey expressed

her own internal conflict and misgivings over the ethics of her research.

So by the time students began the

IRB process for Human Participants, they had all already deeply

considered their own ethical implications for research.

Lindsey and I talked on a number of occasions about

possible consequences of out-ing others or herself. And Lindsey expressed

her own internal conflict and misgivings over the ethics of her research.

So by the time students began the

IRB process for Human Participants, they had all already deeply

considered their own ethical implications for research.

Return to Top

Ethnography and Authorial

Voice

In

constructing these ethnographies, we considered

John Van Maanen's (1988)

classification of ethnographic tales into three categories: Realist,

Confessional, and Impressionist. The differences in these categories

correspond to debates in social anthropology between positivism and

phenomenology -- of whether or not there is an objective, observable

truth out there in the social world, or if experience is always already

mediated by perception. I proposed that students need not resolve this

debate, but that by being aware of the debate, they can make more

conscious and ethically informed decisions in their research and writing.

The Realist ethnography,

according to Van Maanen, is the bread and

butter of anthropology and sociology. In the realist tale, the narrator is

both invisible and omnipotent. The subjective "I" is replaced by the eye

of god, the eye of T.J. Eckleburg, if you recall the billboard in The

Great Gatsby that looked down on Wilson's garage, the eye of dispassionate

judgment.

Van Maanen describes some of the

primary conventions of the realist tale: the invisible author, thick

descriptions of the mundane, and interpretive omnipotence. He adds,

Realist tales are not multi-vocal texts

where an event is given meaning first one way, then another, and then

still another. Rather a realist tale offers one reading and culls its

facts carefully to support that reading. Little can be discovered in such

texts that has not been put there by the fieldworker as a way of

supporting a particular interpretation."(53)

The Impressionist

tale, on the other hand, draws its conventions from phenomenology, post-structural theory, and

feminist theory and attempts to present a multi-vocal view of the culture,

one that is clearly responsible to the natives for ethical treatment. As

Van Maanen explains, "The idea is to draw an audience into an unfamiliar

story world and allow it, as far as possible, to see, hear, and feel as

the fieldworker saw, heard, and felt." Knowledge, in this

impressionist view, is often fragmented, contradictory, and many

theoretical questions are left unresolved and un-resolvable.

The Result

While

most

students chose a “realist” rhetorical strategy, Lindsey instead chose

to exploit the potential of the Impressionist ethnography -- a strategy

that suited her purpose in destabilizing gender identity, evoking the

social construction of knowledge, and transgressing norms .

.

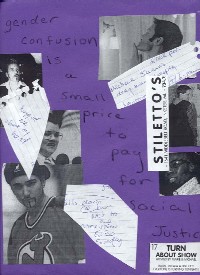

Lindsey

presented her project in a purple binder on which she created a collage

using images of gender bending, fragments of her handwritten field notes,

newspaper clippings, and a handwritten admonition: "Gender confusion is a

small price to pay for social justice." In this project, Lindsey went

native. Exploring her own issues of sexual identity, Lindsey experimented

with cross-dressing, constructing a male alter-ego named Luke. Lindsey's

ethnographic essay itself contained fragmented bits of narrative,

self-reflection, interview and exposition. She transgressed traditional

notions of research and understanding through this impressionistic method.

She transcribed internal monologue, she exposed herself as vulnerable and

unsure, she reflected on her own uncertainties about what she was doing

and her motivation for doing so. She blended history and social analysis

with personal performance and exploration. She drew heavy from feminist

theory to construct an impressionist tale of gender bending in metro

Detroit, attempting to provide evocative knowledge rather than imposing an

interpretation.

Lindsey

presented her project in a purple binder on which she created a collage

using images of gender bending, fragments of her handwritten field notes,

newspaper clippings, and a handwritten admonition: "Gender confusion is a

small price to pay for social justice." In this project, Lindsey went

native. Exploring her own issues of sexual identity, Lindsey experimented

with cross-dressing, constructing a male alter-ego named Luke. Lindsey's

ethnographic essay itself contained fragmented bits of narrative,

self-reflection, interview and exposition. She transgressed traditional

notions of research and understanding through this impressionistic method.

She transcribed internal monologue, she exposed herself as vulnerable and

unsure, she reflected on her own uncertainties about what she was doing

and her motivation for doing so. She blended history and social analysis

with personal performance and exploration. She drew heavy from feminist

theory to construct an impressionist tale of gender bending in metro

Detroit, attempting to provide evocative knowledge rather than imposing an

interpretation.

By academic and

scholarly standards, Lindsey's ethnography was adequate, given the time

constraints of the semester. There were a number of areas in which she

could have explored more fully, drawn more clear connections, developed

her analysis and reflection more richly. But as a personal exploration if

identity and the construction of knowledge, Lindsey's project was a

superior product.

As

Jonathan

Alexander (1997) proposes, we should "encourage all students --

both gay and straight -- to think of ways each identity is shaped by the

stories and narratives that surround and permeate us through the social

clusters of family, friends, colleagues, city, state, country, and

culture" (p. 215). While

Lindsey's final project may have fallen a bit short in terms of

traditional academic

rigor, the project certainly revealed her own insight and promises as a

scholar of gender and identity, and the sophisticated ways in which she

was arriving at her own understanding of cultural power.

As she said later, she was more interested

at the time in coming to her own terms than in persuading others.

However, as Lindsey puts it, perhaps through interacting with her project,

others' "perspectives on the dominant

culture will have been queered, as they look for themselves in the other,

and find the other in themselves."

Return to Top

References

Alexander, Jonathan. (1997).

"Out of

the closet and into the network: Sexual orientation and the

computerized classroom." Computers and Composition, 14

(2), 207-216. Retrieved 30 May 2004 from

http://www.hu.mtu.edu/%7Ecandc/archives/v14/14_2_html/14_2_Feature.html

Bronski, Michael (1998). The

Pleasure Principle: Sex, Backlash, and the Struggle for Gay Freedom.

New York: St. Martin’s Press.

De Castell, Suzanne and

Mary

Bryson (1998). "Queer

Ethnography: Identity, authority, narrativity, and a

geopolitics of text." In J. Ristock & C. Taylor (Eds.),

Inside the Academy and Out: Lesbian/Gay/Queer Studies and

Social Action (pp. 97-110). Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press.

Rose, Dan (1987). Black

American Street Life: South Philadelphia, 1969-1971. Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press.

Van Maanen, John (1988).

Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

Yescavage, Karen and Alexander, Jonathan. (1997). "The

Pedagogy of Marking: Addressing Sexual Orientation in the

Classroom."

Feminist Teacher, 11 (2), 113-122.

![]()

![]()

![]()