I got my first tattoo in my late 20s. On a predictably hot summer day in Washington, DC, I rode my bike out several miles to find a affordable tattoo parlor on some highway in northern Virginia. The young man tattoo artist gave me advice for how to "safely" jump trains while he marked my body with a series of black circles that snake their way up my arm, getting bigger and more painful as they ascend.

People ask me what my tattoo means. I tell them they are dots… just dots. I wanted a tattoo for the purpose of a tattoo. The dots mark a decision to mark my body, to decide what is beautiful and right for my body. This tattoo is a kind of self branding: My body belongs to me. My body is me. It took me until my late 20s to feel entitled to my own body.

Wysocki and Jasken (2004) demonstrated that interface design has traditionally been taught as a method of concealing the designer behind the interface, as if the only significant relationship would be the relationship between the computer and the user. Wysocki later reiterated the significance of embodiment our new media compositions and the knowledge that we produce. She wrote (2003): "Our belief that meaning can exist apart from the material embodiment of printed timetables, pages in bound books, or screens on computer monitors is woven into a belief that what we think has nothing to do with our messy, gendered, raced, aging, nationalized, digesting bodies" (186). The invisible interface, likewise, assumes the separation between embodied designer and the designed interface. McCorkle (2012) traced the history of interface design as it has become invisible, and then urged us: "the job of the technological critic, therefore, must be to agitate that quietude by acknowledging that the gap [between mind/body and machine], and that human programmers and designers will build their bridges based on standardized assumptions and generalizations about the body" (183). I would extend McCorkle’s argument by urging designers as well as technological critics to agitate the quietude of transparent interface design by making our own embodiments as designers visible in our work.

Design to Make Space for Bodies

Despite the effort placed on erasing embodiment, bodies are always present designing, using, creating, and composing. Wajcman’s (2004) theory of technofeminism makes a critical intervention by making gendered bodies the center of her analysis of technologies. She claimed that "by linking gender to technology, technofeminist perspectives add a new dimension to sociological analyses of gender difference and sexual inequality" (p. 116). Her hope was that when women design, our gendered experiences and gendered knowledge will lead to new design choices and new tools. By extension, by making our gendered, racialized, nationalized, aging, strong, broken, and unique bodies visible in our designs, a technofeminist design can break out of hegemonic design standards. For example, by making my body visible on this text, my readers can engage with me as embodied designer–writer, a white body, a woman's body, a tattooed body, a southerner, and unique human being making her way in the world. These embodied experiences frame and inspire my thinking as well as my own design practice.

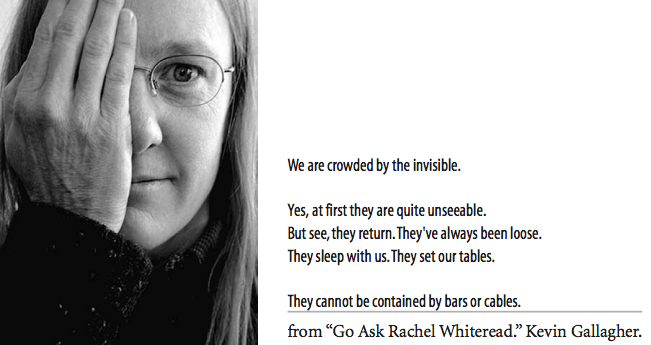

Wysocki and Jasken (2004) designed their print text in a way that makes their own bodies and their embodied networks visible. We cannot forget the faces, half or partially covered, that appear on different pages. In this small design choice, I see the bodies, people and unique faces that make their communities. I see a hand with a wedding ring on one page and faces with beards on others. By partially covering the faces or getting up close to eyes and hands, Wysocki and Jasken suggest that every text is only a partial representation or partial inclusion. There are things we continue to hide. And there are people, bodies, experiences left out. And, yet, audiences see the embodiments that underlie the interface of the page, the theory, and the text.

To make embodiment visible through interface design includes more than sharing a photos of a body. Rather, the technofeminist design integrates embodiment by considering carefully: Whose body? What gestures may invite a relationship with audiences? How do I want to be felt or seen?