We cannot choose where we come from and, to some extent, we cannot choose our family. However, we can choose who we honor. I choose not to honor where I come from. Those are not the communities that I wish to support, honor, and ally with.

I was raised in a fundamentalist, Christian cult. There is a lot of information packed into that sentence, none of which I will unpack for you. At 21, I had to re-build my world, my life, my communities. No one survives what I went through without deep scars. Some don't survive at all.

I don’t have many good things to say about being raised in a cult, but reading scripture aloud daily will result in a community with very high literacy rates. I can swing a hammer better than the average professor: a skill developed while building wheelchair ramps and repairing homes of community members. Most significantly, when one is raised in a cult, one learns to value community... for better or worse.

I’ve heard folks refer to academia as a cult. No, I say, the neoliberal university that places top value on individual accomplishments feels nothing like a cult. Academia is lonely and isolating.

We all had those really bad days while writing our dissertations. I’m not the only one, right? My bad day came in the spring. It felt like the last straw. I was quitting. Ready to give up. I don't think I had spoken to a human in days.

I called an artist, friend, and mentor, Christina Hung. Christina is a feminist artist. I was her student four years previously. I modeled my feminist pedagogy after watching her. I continue to model myself as a feminist friend after her. Could she help me make a plan B for my life? She was at my house in 15 minutes.

My living room was piled high with library books. I think every book I cited in my dissertation was somewhere in various precarious piles.

Christina asked me to lie on my living room floor. I stared up at the ceiling as she gradually buried me in books. It turns out that it’s hard to balance books on skinny arms. She giggled and said "night night" as she placed the books on my face. I asked her to place Judith Butler and Elizabeth Grosz near my heart. Maurice Merleau-Ponty was near my stomach. Just go ahead and hide Martin Heidegger under something else. It was silly and heavy at once. Her photos make me look like a chrysalis, wrapped up in the weight of my own books like a cocoon.

She wrapped me in books. More importantly, she wrapped me in her love and friendship. This friendship, and so many feminist friends, mentors, and collaborators, have become my community.

As I move forward to imagine designs that would honor the places from which I choose to be from, I am making a choice to align myself, my arguments, my texts, and my feminist actions with these communities. In that way, I'm less honoring myself and more honoring those feminists who I aspire to become like. I hear the lyric voice of Cynthia Haynes in my ear. I remember the sound advice of Madeliene Sorapure and Linda Adler Kassner. I giggle with delight as my young friend Erika Carlos helps me figure out how to make the icons on this page shake. I look forward to my next bourbon with Jenn Fishman and my next writing session with the community of women who gather in the library, nearly daily, to write together. I feel the energy that fills each room at Feminisms and Rhetorics and other events hosted by the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition.

Judy Wajcman’s (2004) Technofeminism reminds us that technologies always work within social networks. Within these networks, technologies become actants that have the power to act upon users. However, our technologies do not act upon all users in the same ways: There are gendered, classed, racialized differences that affect how we interact with technologies and interfaces. Women are acted upon; we do have some power, however, to respond and appropriate tools into new uses and new networks. This is where Wajcman sees hope and the promise of technofeminism.

Design to make communities visible.

Technofeminist design can make visible those social and technological networks within which I work and toward which I wish to continue working. By making these networks visible in our designs, a designer can honor those who came before and those who led the way. In addition, a technofeminist rhetoric of design would make visible social, material, and technological networks of composition. Sara Alvarez et al. (2017) recently published a multimodal research project in Kairos that documents and analyzes the complex multimodal composing process of several authors. From this reflection and documentation process, they conclude

"Composing changes, moves, shifts, and evolves with our bodies and the tools we adopt/adapt. Composing is social, mobile labor. Indeed, it's impossible for us to imagine, to see, composing as anything other than extremely networked, ecological, and therefore unceasingly complicated—dependent on (f)actors as diverse as technical skill and physical comfort. Our experiences of being human perhaps count as much as (or more than, perhaps) our official educations as composers." (emphasis mine)Their Kairos article makes visible the complicated network that makes up the multimodal composition process of their own authors. We see the spaces, pets, tools, and rituals that these authors build into their composition process. So too, when I design as a technofeminist, I also want to make visible the complex process of composing, which includes our experiences of being a human.

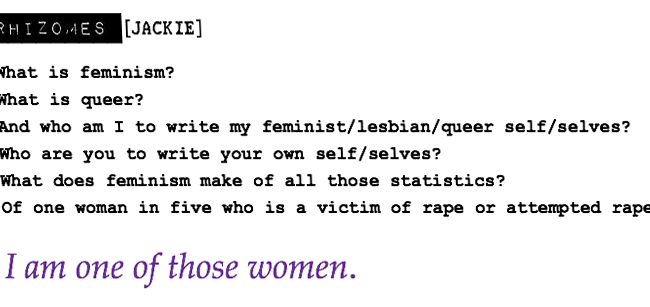

Like Jackie Rhodes, I too spend a lot of time in my garden and I also find traction with the term rhizome, though I will specifically to consider rootstock. Rhodes and Honathan Alexander (2015) offer us a theory of feminist rootstock:

In botany, and in my garden, a rhizome is known as rootstock, which grows and spreads through multiple nodes underground, and which might send up a flower from any and all of those nodes.” As a novice gardener, I tended to plants and fruit as if those are separate distinct entities. Now, with more experience and with the hard lessons learned from many dead plants, I tend for the complex ecosystem, which includes thinking of the health of my garden below the surface of the dirt. Rootstock reminds us that there is always more beneath the surface.

Rootstock reminds us that beneath every publication, idea, course, or author, there is a broader community and intellectual tradition. Just as the strawberry is the small fruit made possible by its intertwining connection to the entire strawberry patch, the rich life of the soil, and the ecosystem of the garden as a whole, so too the fruits of our intellectual labor are made possible not by individual writers but by entire communities and intellectual systems within which we work, think, live, and grow. In particular, feminist intellectual traditions and feminist communities are the roots, out of which my intellectual labor appears as one node or one berry.

Rhodes (2015) theorized feminist rootstock as a way of thinking about not just composition in relation to technologies but also the importance of place, intersubjectivity, and embodiment:

A feminist take on the rhizome renames it rootstock, for questions of place and space are crucial if we insist on embodied and ethical commitments to justice. The rhizome works flatly through lines rather than static point, but rootstock might dare ask Deleuze's "useless questions," for that reaching is part of an identity. Longing. This longing, too, is a tangled line. Indeed, we might say that a feminist rhizomatic or rootstock most resembles Rosi Braidotti’s nomadic subject, a vision of subjectivity that embraces simultaneity and multiple, sometimes contradictory layers of identity.Rhodes and Alexander also make this feminist rootstock visible in their design of Techne. They make visible their “multiple, sometimes contradictory layers of identity.”

Rhodes and Alexander show us a slideshow of their many selfies, which are at times playful, awkward, confident, and at ease. They also offer us videos depicting their roots. We see a hand grasping and losing soil as Rhodes’ voice narrates her feeling of displacement growing up queer in a rural Montana town and church. In these videos, we hear rejection and disciplining of her embodiment. Alexander tells us the story of his gay uncle. In these stories, we see Alexander’s joy, pride, belonging, and feeling very out of place. Rhodes and Alexander make visible their lived experiences as humans and also the network of scholars, family members, friends, and partners who make up their rootstock. Out of these communities, Rhodes and Alexander theorize, narrate and design their queer techne.

I love this text. Whenever I turn to it, I get a bit lost in its capacious, unstable modes of composing arguments and ourselves. The authors reflect upon how technology and media have shaped their experiences and they use media to re-compose and explore their histories, sexualities, and experiences.

When I design as a technofeminist, I do not seek invisible interfaces. Rather, a technofeminist design features the designer in her particularity and cultural context. These words and this text come from somewhere and from some body (from my body, which feels like it’s from South Carolina but presently types in California). A technofeminist design may make that network of bodies, technologies, peoples, and values visible.

Design choices can function in the same way as our citational practices. Citations inform the readers who we are in conversation with, who we are are inspired by, informed by, and who we may be diverging from. These are the shoulders upon which we stand. Sara Ahmed (2013) has argued that citations are reproductive technologies, “a way of reproducing the world around certain bodies.” Design choices can also signal the communities within which we belong and the bodies that we include in those communities. We belong to academic communities. We may visually signal that we belong to that community through the use of Times New Roman, 12pt font, and 1-inch margins. However, these academic communities are not our only communities. We belong to communities of our families, friends, local spaces, home towns, queer folks, and feminist friends. These communities also inform my thinking, values, writing, and aesthetic preferences. I can "cite" from these communities by embedding design elements affiliated with these communities.

These design citations can also function as an invitation. Visually, these invitations indicate the community within which I identify. At the same time, the design choices invite readers who may also identify themselves within the design and discourse community. With the color, font, images, and layout, we align ourselves with different communities and their aesthetic traditions and conventions. Rather than aligning ourselves with corporate, colonial, masculine spaces, what communities are we going to signal that we belong to? These communities are intersecting, complex rootstock of our lives.

I am one particular woman, writer, and feminist making choices of what communities that I belong to, support, or admire for their design aesthetics. You likely align yourself or respect other communities. No single text can make visible the full complexity of these communities. Instead, we make choices. Maybe you draw upon your home or city, your grandmother's memory, or your auntie's words of wisdom. Maybe your inspiration comes from dresses, scrapbooks, or needlework. What narrative will I tell this time? What communities can I honor, celebrate and amplify with this design?