Footnote

X

Results: Section Overview

This section provides part of the results from the study I conducted. As I explained in the Methodology Section, the information presented below is based on a total sample of 908 First-Year-Students. As the data included below suggests, participants included in the sample had mixed experiences when it comes to using the types of technologies I wanted to see if they were familiar with, what activities they frequently engaged in while online, and how much time they spent online or using a computer.

Results: Access to Technology

Part of the reason I ran the study was to determine if the participants had access to a few digital communication technologies while in high school. Although many of the participants did have access to those technologies, based on their responses, some of the participants had little or no access to the technologies included in the distributed survey.

As Figure 3.1 in the Methodology Section illustrated, eight questions on the survey I distributed asked participants if they had access to a few digital technologies often used to create digital compositions while they were in high school. The reason I included those questions relates to pedagogy. When creating digital compositions, students will eventually need to use at least one digital technology to mediate their work. Knowing what technologies the students do, or do not, have familiarity with can change a first-year composition instructor’s pedagogical approach when including those types of compositions in their courses.

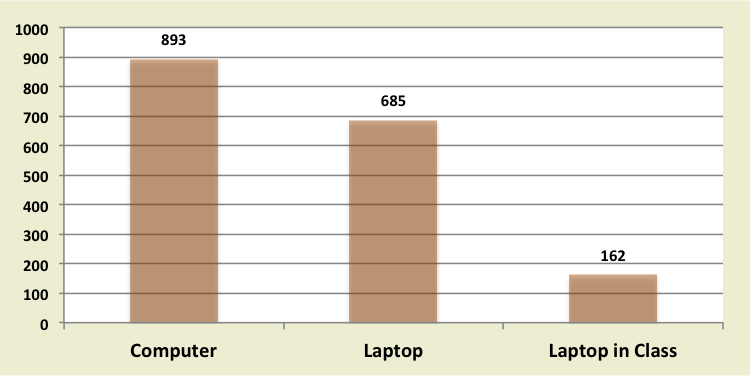

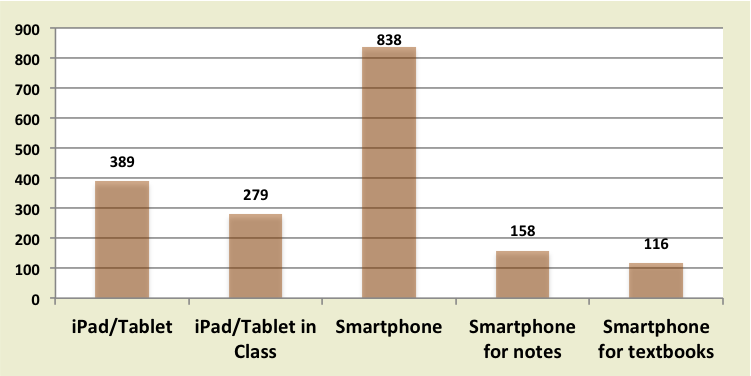

Participant responses to the access-based questions were mixed. As Figure 4.1 and Figure 4.2 indicate, eleven participants claimed they did not have access to a computer where they lived while in high school. All of those participants also claimed they did not own a laptop. Three of those participants claimed they did own an iPad or tablet and all three took that technology to class. Nine of those participants claimed they did own a smartphone, but only one used it to take notes and none of those participants claimed they used a smartphone to access their textbooks. One participant from the sample also claimed they did not own any of the listed technologies while attending high school.

Results: Multimodal Composition Experience

A secondary motivation for running the study was to see if the participants had prior experience building multimodal compositions. Based on their responses to the distributed survey, some of the participants did have some prior experience building a multimodal composition, but those projects were not usually completed for an English course.

As illustrated in Figure 3.2 of the Methodology Section, the distributed survey included questions to find out if the participants had completed any assignments while in high school that required them to complete some basic multimodal activities. The reason I included those questions on the survey was directly related to my interest in familiarity. I wanted to know, specifically, if some of the tasks associated with building a multimodal composition had become somewhat ubiquitous to the participants and could be easily included as part of a first-year composition assignment without much technology-based instruction on the part of the instructor. Conversely, I also wanted to know if there was a pattern of unfamiliarity among the participants, which would need to be addressed by a first-year composition instructor when assigning digitally mediated multimodal projects in their courses.

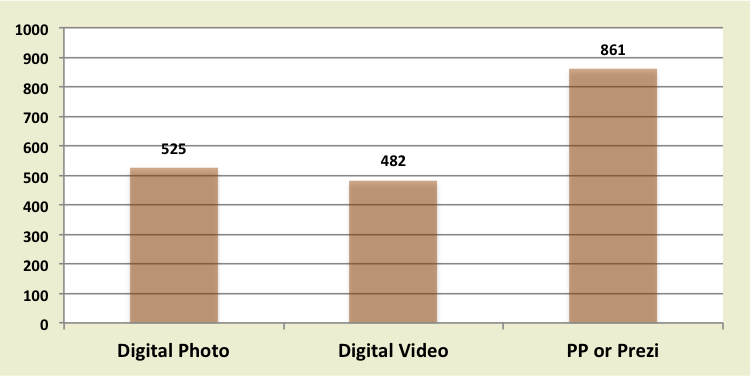

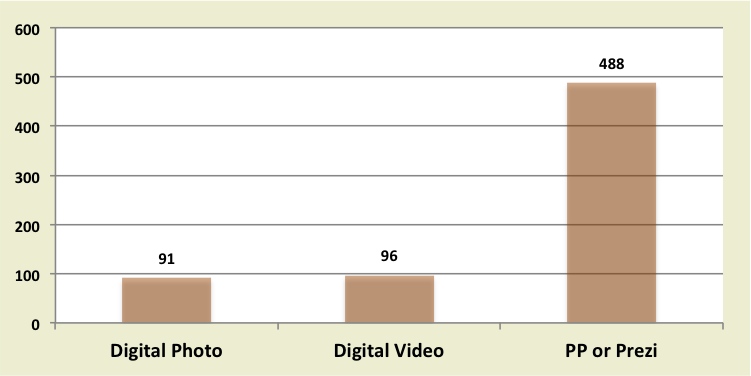

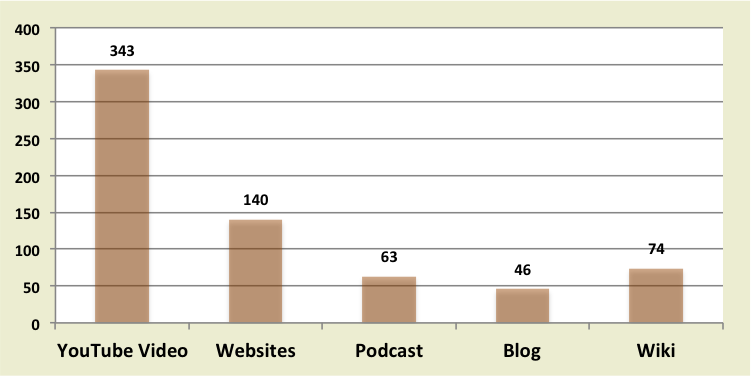

Like the responses to the questions regarding access, participant responses to the questions pertaining to multimodal activities completed as part of an assignment while in high school were mixed. See Figure 4.3 for participant responses to those questions. As Figure 3.2 in the Methodology Section also indicated, those questions included follow up questions asking the participants to identify which class(es) required them to complete the activities included in the survey.[1] Figure 4.4 includes totals of how many participants claimed those activities were completed as a requirement for an assignment in an English course.[2]

Results: Online Content Production

In addition to the questions referenced above, I also wanted to see if the participants had prior experience uploading digital content to the Internet. Based on their responses, participating in social media networks was the only online content production practice shared by almost all of the participants.

As Figure 3.3 of the Methodology Section indicated, the survey included five questions designed to understand if the participants were producing or sharing digital content outside of their classroom-based experiences. What I wanted to know by including those questions was if the participants were voluntarily engaging in digital content production on their own. In other words, I wanted to see if the participants had produced text-based digital content or multimodal compositions in their spare time when they were not required to do so as part of an assignment for one of their classes.

Once again, the questions related to content production were also designed around the idea of discovering patterns of familiarity among the study participants. As Figure 4.5 illustrates, participant response to the questions regarding online content production were mixed. In addition, all but two of the participants claimed they participated in at least one social network regularly. Four of the most popular social networks the participants claimed they belonged to included Facebook (72%), Twitter (56%), Instagram (76%), and Snapchat (75%).[3]

Results: Expertise and Usage

The last major category of questions included on the distributed survey pertained to the participants’ self-perceived levels of expertise and usage. Based on their feedback, a majority of the participants did view themselves as almost experts or experts using a computer, the Internet, or a smartphone.

As displayed in Figure 3.4 of the Methodology Section, the survey included five questions related to how much time the participants spent online, how much time they spent using computers, and how they viewed their own level of expertise when it comes to using specific digital technologies.

The reason I included questions related to time and self-perceived levels of expertise was because, as I further explain in the Discussion Section, I was interested in discovering if there was a correlation between the participants’ self-perceived level of expertise, or how much time they spent using digital technologies, and the types of compositions they claimed they had produced. I wanted to know, specifically, if familiarity with using a digital technology meant the participants were more likely to produce the type of content often included in a digitally mediated multimodal composition.

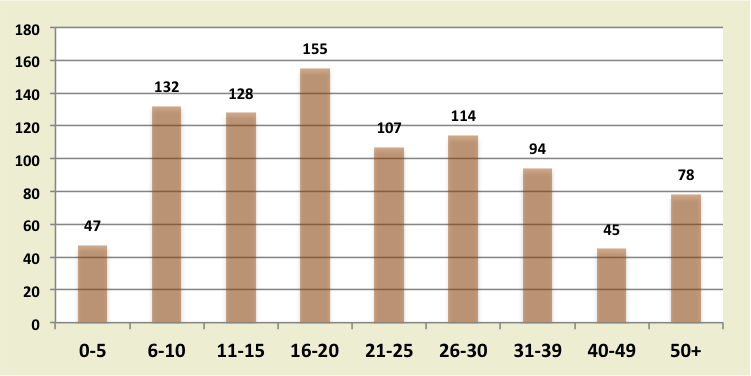

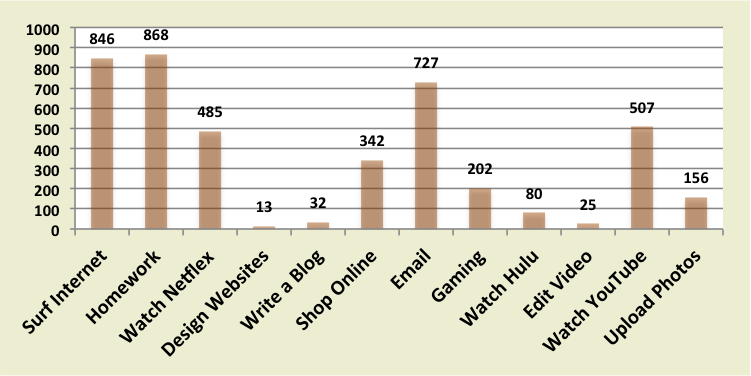

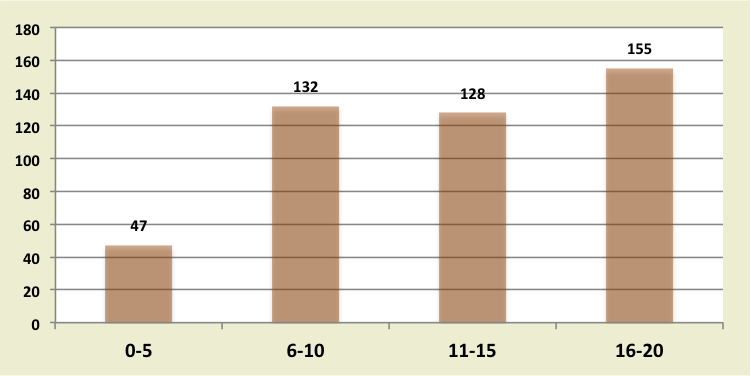

When answering questions related to expertise, the participants had the opportunity to self-rank based on a scale of 0 (beginner) to 5 (expert). The mean score for the question regarding computer expertise was 3.7 with a standard deviation of 1.26. One participant claimed to be a beginner (a response of 0), 47% ranked their own expertise at 4, and 13% ranked themselves as experts (three participants did not answer the question and 2 participants claimed to be more than experts). In other words, 60% of the First-Year-Students who participated in the study claimed they were almost experts or expert computer users. Figure 4.6 illustrates how many hours the study participants claimed they spent using a computer during an average week. Figure 4.7 illustrates the activities the participants claimed they used a computer to complete during their average day.

The mean score for the question regarding their self-perceived level of expertise using the Internet was 4.01 with a standard deviation of .784. One participant claimed to be a beginner (a response of 0), 47% ranked their own expertise at 4, and 26% ranked themselves as expert users (2 participants left that question blank). Meaning, 67% of the participants claimed they were almost experts or expert Internet users. Figure 4.8 illustrates how many hours a day the participants claimed they use the Internet.

The mean score for the question regarding the participants’ self-perceived level of expertise using a smartphone was 4.25 with a standard deviation of 1.905. Four participants claimed to be beginners when it comes to using smartphones (a response of 0), 43% ranked their own level of expertise at 4, and 41% claimed they were expert smartphone users. The total number of participants who claimed they were almost experts or expert smartphone users was 84%.

Results: Focus Group Sessions

As I discussed in the Methodology Section, in an attempt to gather additional information from the study participants and have them expand on some of the questions included on the survey, I recruited 23 sample participants to participate in small focus group sessions. Like the questions included in the distributed survey, the questions I asked each focus group were intended to see if the participants had similar experiences with some common tools and platforms used to prepare and post digital content online. Similar to the response the participants provide when completing the survey, not all of the focus group participants had previous experiences using some very common digital technologies or digital content distribution platforms while in high school.

The first questions I asked during all of the focus group sessions, as displayed in Figure 3.5 of the Methodology Section, pertained to the participants’ level of familiarity with word processors and some of the features included in Microsoft Word®. Although handwritten essays and essays composed in a word processor are only two modes of communicating, understanding the participants’ familiarity with composing texts using a digital tool like a word processor is important to my study and, as I discuss in the Discussion Section, does have pedagogical implications.[4]

Although all 23 focus group participants claimed they used Microsoft Word® in the past, three of the participants also claimed that most, or all, of the essays they wrote for their English classes in high school were hand written. As one participant claimed, I mainly hand wrote mine because we had to do a lot of in class timed [essays] we didn’t do a lot of research papers outside of class.

During the focus group sessions, I also asked the participants a few follow up questions regarding Microsoft Word®. All of the focus group participants claimed they knew how to insert an image into a Microsoft Word® document, but most of them said they accomplished that task through copy and paste. A few of the participants also claimed they had never added a caption to an image in a word processor.

In addition to the word processor related questions, I asked the participants of each focus group session a few questions related to capturing and editing digital photos and videos (see Figure 3.6 of the Methodology Section). These questions were asked during the focus group sessions because, as I explain in the Discussion Section, familiarity with capturing and editing digital images and pairing that mode of communication with text is often included as part of a student’s first exploration into the development of a digitally mediated multimodal composition.

All of the focus group participants claimed they had taken a digital photo and most claimed they had taken at least one image with their smartphones. When asked if they had ever edited a digital image, one participant claimed, For a class, no […] for personal use, yes.

Another participant claimed, If I am editing it [an image], it is usually for social media.

However, three participants claimed they had never edited a digital image and at least one participant from all but one focus group claimed the only edits they had ever made to a digital image was adding an Instagram filter.

Like the response I got pertaining to digital images, the responses to the questions regarding digital video were also mixed. Although each focus group participant claimed they had captured digital video, four participants claimed they had never edited a digital video. Additionally, at least one participant from six out of the seven focus groups claimed the only edits they had ever made to a digital video was shortening the footage. Furthermore, only four participants claimed they had experience adding text overlays or captions to the videos they edited.

Results: Summary of Collected Data

According to the survey responses collected from the sample participants and the responses I got during the focus group sessions, when it comes to issue of access, familiarity, and experience composing digitally mediated multimodal “texts” there simply is no indication of ubiquity. In fact, as the information above has described, one of the few overarching claims I can make based on the collected data is that the participants’ level of familiarity was mixed. Some participants appear to have great familiarity with the tasks and activities covered by the study. However, other participants had very little, limited, or no familiarity with many of the tasks covered by the study.

Although a large number of the sample participants claimed they had some experience completing a few common tasks generally associated with building a digital composition or producing a digitally mediated multimodal assignment, only a little over 10% of them claimed they took a digital photo or a digital video as part of an English assignment. A closer look at the responses also indicated that the digital photos were often taken as part of a creative writing assignment and the digital videos were captured as part of a literature sequence where they acted out and recorded parts of a literary work. Additionally, and more significantly, eleven participants claimed they did not have access to a computer where they lived in high school and did not own a laptop computer. In total, 70 participants did not own a smartphone while in high school and only 17% of the sample participants who claimed they owned a smartphone while in high school used their smartphone in class.

All of the discoveries have some level of significance. But, the data I have included up to this point in the web-text only provides partial answers to the questions that led me to initiate the study as outlined in the Background Section. Something I was not expecting to see in the data and what the answers to the individual questions do not yet demonstrate, is if the participants view the ability to complete a task associated with preparing a digitally mediated multimodal composition as something they include in their self-assessments regarding technological expertise. Furthermore, the data included above does not reveal what additional rhetorical choices the sample participants might have made before posting the digital content they produced outside of a classroom assignment. Therefore, to help contextualize the numbers listed above, I have included some further data analysis in the Discussion Section.

Notes

- The follow up questions regarding the type of class(es) was included to see if the participants were completing those activities specifically for an English class.

- The totals in Figure 4.4 only include responses specifically identified as English, Literature, or Creative Writing courses. Responses like “All,” “Most,” “Every,” etc. have been excluded from this total.

- The participants claimed they belonged to a large variety of social networks. I have only included four here because including them all would take up too much space in the web-text.

- The reason I focused on Word® is because it is the application available on all UAB computers and is free for the students while they are registered for classes.