Footnote

X

Discussion: Section Overview

Further analysis of the data presented in the Results Section is included below. As I explained in the Participant Section and Methodology Section, the information presented below is based on a total sample of 908 First-Year-Students. Additionally, as I mentioned at the end of the Results Section, this section of the web-text was included as a way to parse through and make sense of the data presented earlier. This section further analyzes some of the data to see if familiarity factors into the sample participants’ claims regarding technological expertise. It also further explores the types of rhetorical choices the sample participants might have made regarding the digital content they produced prior to the study. In addition, it includes some brief and localized pedagogical implications based the provided analysis.

Discussion: Online Activities and Expertise

Although multimodal compositions do not have to be digital, many common assignments typically referred to as multimodal are born and developed digitally. Assignments like building a website, creating a podcast, or any project where the students must design both the content and the structure of the document are just some examples. In each case, the skills the students will need to learn and the tasks they will need to perform to complete the project will also vary from assignment to assignment. But, completing a completely digital assignment does require some familiarity with basic and advanced digital technologies. Because the data regarding the participants’ prior digital/multimodal content production experiences presented in the Results Section were so mixed, what follows is a closer look at how different levels of familiarity with using a computer or the Internet might account for the range of experiences and types of digital content the study participants claimed they had produced.

By embracing the goals outlined in the CCCC Position Statement on Teaching, Learning, and Assessing Writing in Digital Environments (2004), and given the fact that many multimodal assignments do require a familiarity with digital technologies, the study I conducted included the opportunity for the participants to self-rank their own level of expertise with some basic digital technologies (see Figure 3.4 in the Methodology Section). This type of data collection is important for a localized assessment because it puts judgment in the hands of the participants rather than basing levels of expertise on a preconceived list of activities prepared by the researcher. It also starts to identify whether or not the participants’ self-perceived levels of expertise are accurate. Although the data I collected does not specifically reveal what activities the participants included in their own assessment of expertise, when compared to some of the tasks included in the study the data does yield some interesting results.

As the Results Section indicated, 853 participants claimed they used a computer more than six hours every week, 508 participants claimed they used the Internet more than six hours a day, and 846 of the participants do use the Internet during their average day. Based on those numbers, it can be assumed that a large number of the study participants were using a few different digital technologies almost every day. However, what the numbers do not show is how much of an impact using a technology every day had on the participants’ self-perceived levels of expertise.

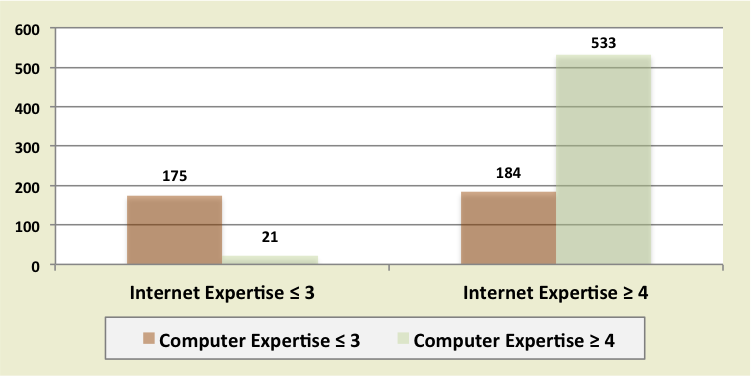

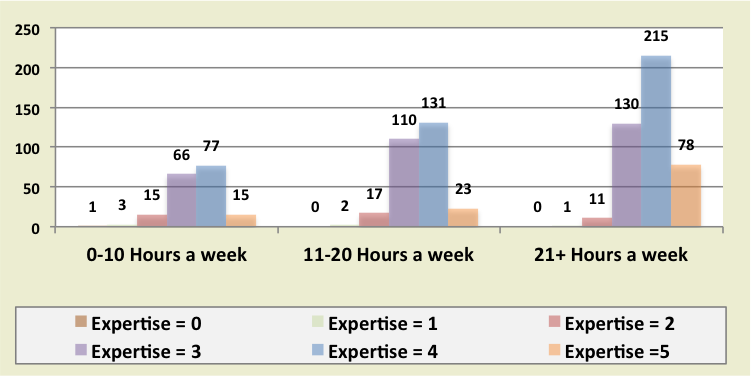

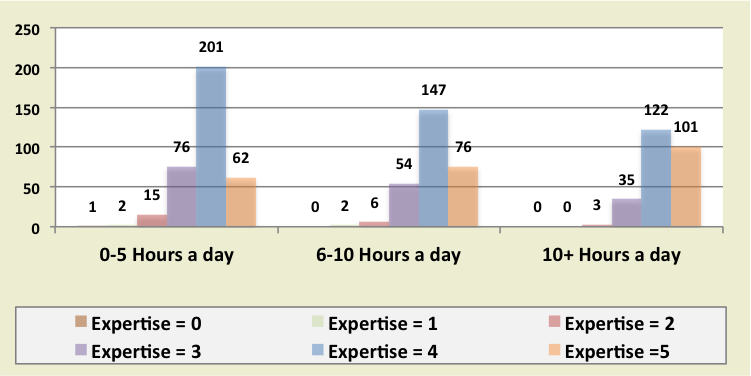

As Figure 5.1 illustrates, those participants who self-ranked their level of expertise with computers at four or five on a scale of 0 (beginner) to 5 (expert) were also more likely to rank their own level of expertise using the Internet at a four or five. The correlation between how often the study participants used a computer during their average day and their self-perceived level of expertise using a computer, as illustrated in Figure 5.2, was not as significant. But, as Figure 5.3 demonstrates, there is a correlation between the amount of time the participants claim to be on the Internet every day and their self-ranked level of expertise using the Internet. Based on the collected data, it appears that those participants who used the Internet more often every day were more likely to rank their level of expertise higher.

One additional comparison that can be made from the collected data deals with the participants’ self-ranked levels of expertise and the activities they completed using a computer and the Internet. This comparison is also important to a study focusing on localized assessment because the participants may claim to be experts using computers or the Internet, but their self-assessments of expertise may not include familiarity with the types of tasks they will need to complete in order to successfully navigate a digitally mediated multimodal composition assignment. In other words, one question I had when developing the study was: Will some of the activities normally associated with completing a digitally mediated multimodal assignment factor into the participants’ own self-ranking systems?

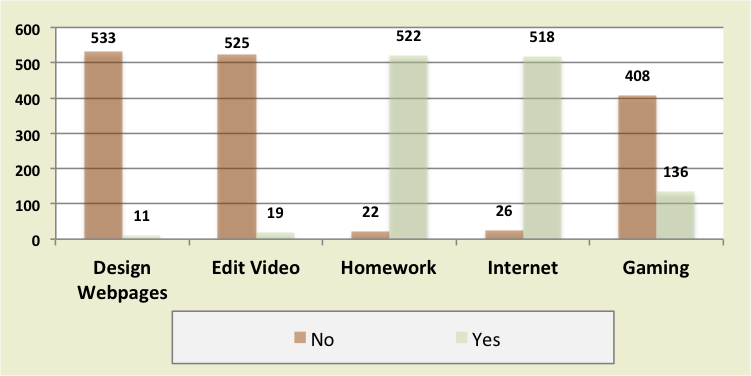

One example includes building websites. As the Results Section indicates, 544 study participants self-ranked their level of expertise using a computer at almost expert level or at the level of expert. However, only 101 of those participants claimed they had built a website before taking the survey. As Figure 5.4 illustrates, the same participants who claimed to be almost an expert or expert computer users do not include Designing Webpages as part of their typical use habits. Instead, working on their homework and browsing the Internet are two activities included in their daily activities.

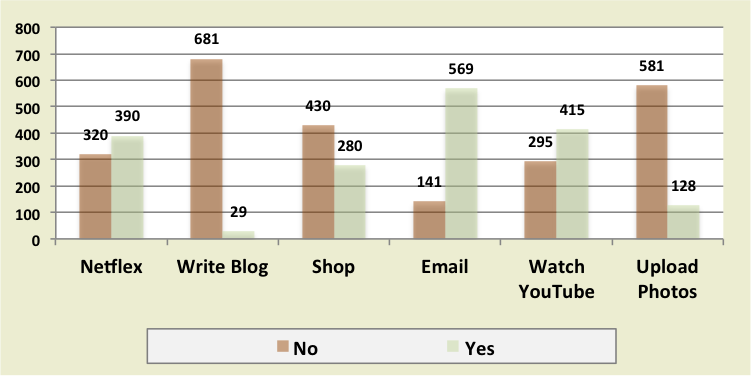

Similar to the types of activities the expert and almost expert computer users claimed they completed, the types of activities the expert and almost expert Internet users completed were often more focused on digesting information than creating information. According to the survey data reported in the Results Section, 711 study participants self-ranked their level of expertise using the Internet at almost expert level or at the level of expert. However, only 295 of those participants claimed they had ever uploaded a video to YouTube. As Figure 5.5 also indicates, most of those participants do not include blogging or uploading photos as part of their daily use habits. On the other hand, watching Netflix and YouTube videos was included by many of the participants as an average day activity. In sum, students rated themselves as Internet experts even though their use was largely consumption, not creation.

Discussion: Rhetorical Choices

Beyond exploring how familiarity impacts the type of digital content the sample participants claimed they produced, part of what I wanted to try and understand when designing the study was if the participants engaged in any editing practices before they posted content online. More specifically, I wanted to know if the participants were making rhetorical choices concerning how their audiences would view the visual content they have posted or if they were more likely to post unfiltered and unedited material. The reason I wanted to understand this behavior is that many digitally mediated multimodal assignments incorporated into a composition course often require students to use images or some type of digital video.

Often, visual and video-based assignments in composition courses seek to help students strengthen their visual literacy practices so they can make rhetorical choices when using visuals in their work. As Cynthia Selfe (2004) has explained:

By visual literacy, then, I will refer to the ability to read, understand, value, and learn from visual materials (still photographs, videos, films, animations, still images, pictures, drawings, graphics)—especially as these are combined to create a text—as well as the ability to create, combine, and use visual elements (e.g., color, forms, lines, images) and messages for the purposes of communication. (pg. 69)

Additionally, as Megan Adams (2014) has argued, the integration of a multimodal project helps students begin to understand the importance of rhetoric in argumentative writing

(Rhetoric section). As Selfe and Adams’ arguments articulate, the act of capturing digital images or videos can include rhetorical choices, but how the students edit those visuals after they are captured can sometimes determine the students’ level of success with a multimodal assignment.[1]

According to the data I included in the Results Section, some of the study participants do have at least minimal experiences editing digital images and digital videos. The results showed that 690 participants included in the sample claimed to be members of Instagram and in addition to the focus group participants who claimed they were familiar with Instagram’s filters it can be assumed that some of the participants from the larger sample used the preinstalled filters provided by the application. The data also shows that 621 participants claimed they captured a digital video—either for personal use, for a class, or for both—and 343 participants claimed they had prior experience uploading videos to YouTube. However, further examination of the data shows that out of the 343 participants who claimed they had uploaded a video to YouTube, 245 claimed they did edit those videos before uploading them and only 49 of those participants claimed they changed the privacy settings from the default option of “Public.”

As the focus group responses included in the Results Section also demonstrate, some of the participants included in the study had no experience editing a digital image or a digital video. Additionally, as Figure 5.4 illustrates, most of the sample participants do not appear to see a correlation between their own self-ranked levels of expertise using a computer and editing videos. Only 19 of the sample participants who self-ranked themselves at the level of almost expert or expert computer users included editing digital videos as part of their typical use habits. Plus, as the quantitative data indicates, some of the participants may not own the equipment necessary to capture a digital image or digital video because 70 study participants did not own a smartphone while they were in high school and 25 participants claimed they did not own a laptop, a tablet, or a smartphone while in high school.

Based on the analysis provided above, the study data does provide a few localized pedagogical implications. Because there is a lack of ubiquity among the sample participants’ answers associated with editing digital images, capturing and editing digital video, or uploading content to a social site like YouTube, UAB instructors will need, as I explain in more detail below, to consider the amount of technological support they will be able to provide their students before integrating digitally mediated multimodal assignments into their first-year composition courses. The type of support a UAB student will need will vary, but the study data suggests that many students might need help understanding how to edit a digital image without Instagram before including it in their work.

Further, access to the technology required to first capture a digital image or digital video might be an issue for some First-Year-Students at UAB. This is especially true for some of the sample participants. Capturing the visual, moving the visual to a location where it can be edited, and then editing the visual are all tasks associated with building digitally mediated multimodal assignments some First-Year-Students at UAB could find very frustrating. It would be even more frustrating for some of the sample participants unless those participants who claimed they did not have access to the mobile technologies included in the survey while they were in high school have gained access one of those devices, own a digital camera, or own a hand held video recorder

Discussion: Localized Pedagogical Implications

As I explained above, the types of digital/multimodal artifacts students might complete in a composition course vary. But, because I contained my study to First-Year-Students and incorporating digitally mediated multimodal assignments into a first-year composition course, I would like to end this section with a brief look at how the collected data and the analysis provided above does have some localized pedagogical implications. Because what I have presented is a localized study, the pedagogical implications shared below are tailored toward First-Year-Students at UAB. However, instructors at other institutions may be able to use some of the suggestions I have included, especially if they conduct a similar study and discover findings that are similar to the present study.

Pedagogically, the data included in the Results Section and analysis provided above does offer a few points of caution for UAB instructors who want to include digitally mediated multimodal projects in their first-year composition courses. Regardless of the type of digitally mediated multimodal composition students might complete as part of their course work, students will more than likely need to navigate Craig Baehr and Susan Lang's (2012) concept of cross-application configuration.

Even though Baehr and Lang focus on technical communication practices, their claim that a digital rhetorical artifact is usually not constructed with one computer application, but is composed in multiple applications and then combined is applicable when considering multimodal compositions (p. 54). One simple, and often used, example of this “cross-application configurations” would be an essay assignment that requires students to combine captioned images with their text, which requires both a word processor and, at minimum, a digital camera to complete.[2]

I cannot claim with any certainty that all of the participants included in the study or every First-Year-Student on UAB’s campus would have had similar experiences to the ones I discussed in the Results Section. What I can claim from the data I collected and the focus group sessions is that some of those students do not have all of the necessary skills to complete the simple digitally mediated multimodal composition I described above. This is especially true regarding adding captions to an image, which is required in an MLA formatted essay, without conducting some research first or asking the instructor for help.

Further, the data I collected form the sample participants and the analysis above also reveals one important consideration for all UAB first-year composition instructors. The fact that some of the sample participants had no prior experience typing the essays they prepared for an English course while in high school is significant. It means that unless they were taught MLA in a different course, there is a high potential that every EH 101 course offered on UAB’s campus will include students who are not only attempting to learn how to write a college level essay for the first time but also learning for the first time how to use a word processor to format their work according to MLA guidelines. Creating hanging indents for their Works Cited entries, including a running header on all of their pages, and even learning how to double space their work could be an obstacle for those students.

Although her overall argument deals more with issues of curriculum and access, the results of the study do highlight one important claim made by Mickey Hess (2007). According to Hess, Without devoting careful attention to some of the nuts-and-bolts matters, teachers may be asking students to do the impossible when they compose multimodally

(p. 35). Addressing some of the often-overlooked “nuts-and-bolts” activities associated with formatting an MLA essay is something all EH 101 instructors on UAB’s campus should consider. Plus, as I explain below, if the tasks required to complete an assignment become more complex, UAB instructors will also need to consider how they can help students complete almost every task associated with finishing the assignment.

Based on the results of the study, I have made some changes to my own pedagogical approach when assigning digitally mediated multimodal assignments in my first-year composition courses. One major change to my pedagogy that I have needed to make over the last few years is very close to Daniel Anderson’s (2008) concept of a “low-bridge” and “entry-level” approach. Like the idea of scaffolding assignments that become more and more rhetorically complex as the semester progresses, each assignment I have students complete throughout the semester helps prepare them for the type of digital/multimodal work they will need to complete in later assignments. Because I teach in a computer classroom, I am also able to include mini workshops in each assignment sequence, usually ten minute how-to-tutorials at the end of class, designed specifically to help students become familiar with each task they will need to complete in order to finish the assignment they are working on.

In addition to in-class activities designed to help my students strengthen their rhetorical awareness, each assignment sequence includes in-class activities to help my students understand the rhetorical affordances of the technologies they use to compose their “texts.” Beginning with the first assignment of the semester, my first-year composition students use images in their essays. At this stage in the process I show the students how to complete some basic MLA formatting and I also show them how to insert, crop, frame, wrap text around, format, and add captions to images in a word processor. Later in the semester students prepare a PowerPoint® or Prezi® they can use during a classroom presentation. The workshops I offer at this stage in the process deal with transitions, rhetorically designing slides, and a number of activities that get the students familiar with the interfaces of PowerPoint® and Prezi® .

In the final project of the course, the students convert their presentation visuals into stand-alone video compositions (normally a narrated slidecast) or develop a mini documentary based on their selected topics. Like developing their presentations, the students have a choice here because I know, based on the data I collected, that a number of my students will have never edited digital videos, but some will have had those experiences. In each case, during the final project sequence I provide small workshops designed to help all of the students gain familiarity converting their presentations into stand-alone videos.[3]

Discussion: Summary

As I explained above, when further analyzed, the data provides some interesting results about students’ technology experiences and self-perception of their technology expertise. Typically, study participants did not include many of the tasks or skills required to build a digitally mediated multimodal composition in how they ranked their own levels of expertise using the included digital technologies. Instead, surfing the Internet and digesting, rather than creating, digital content appears to be the types of activities the sample participants completed most frequently. As I have also demonstrated, further analysis of the collected data offers some pedagogical implications. Most notably, although many of the sample participants have some experience with some basic tasks and skills associated with building a digitally mediated multimodal composition, other sample participants do not and have limited experiences preparing a typed and MLA formatted academic essay.

The assignments I have been describing are somewhat simple when compared to the types of digitally mediated multimodal assignments some UAB students might be able to complete in a first-year composition course. Although some of the students may not need instructions on how to include an image or add a caption to an image in a word processor application, offering them a reminder or a different way to accomplish the task does not hurt their development. More importantly, the information I gained from the study has allowed me to tailor my assignments to help the students with less technological familiarity progress through each assignment sequence and end the semester with a multimodal product many of those students have never built before. But, as I explain in the Conclusion Section, the study data also reveals a number of other assessment-based implications beyond those I can include in this section of the web-text.

Notes

- Capturing and editing an image could easily be completed with a smart phone, but the student would still need to use two different applications (the camera app and a photo editor).

- Editing—in particular cropping, resizing, and framing—is often how the students transform the raw images or videos they capture into a contextualized visual that fits the space and context of the assignment.

- I also cover the fact that some computers do not allow you to include voice recordings when exporting a presentation project as a video.