|

Turning to the teaching body as an object of reflection presses upon familiar tensions between theory and practice and the potentially competing ways we come to know how to be a teacher. Highlighting the erroneous and implicit preference for theoretical knowing, performance studies theorist Dwight Conquergood describes these competing modes of knowing as follows:

The dominant way of knowing in the academy is that of empirical observation and critical analysis from a distanced perspective: "knowing that," and "knowing about." This is a view from above the object of inquiry: knowledge that is anchored in paradigm and secured in print. This propositional knowledge is shadowed by another way of knowing that is grounded in active, intimate, hands- on participation and personal connection: "knowing how," and "knowing who." This is a view from ground level, in the thick of things. This is knowledge that is anchored in practice and circulated within a performance community, but is ephemeral. (146) |

|

|

Conquergood, while valuing the second kind of knowing, reminds us that one implicit problem with this active, “ground level” practitioner knowledge is its ephemerality, its resistance to codification, stability or circulation. In the context of teacher-training, accessing this ephemeral “knowing how” is of utmost importance, but difficult to access. As Conquergood suggests, when we privilege theoretical, distanced knowledge, we miss a “whole realm of complex, finely nuanced meaning that is embodied, tacit, intoned, gestured, improvised, coexperienced, covert-and all the more deeply meaningful because of its refusal to be spelled out” (146). Working to counteract both ephemerality and a lack of explicitness, multimodal inquiry is uniquely capable of uncovering embodied teaching knowledge, enabling novice teachers to access and explore what Donna Haraway names a “homely and vulnerable ‘view from a body’ in contrast to the abstract and authoritative ‘view from universal knowledge’ that pretends to transcend location (1991:196)” (in Conquergood 146). Multimodality uniquely renders the in-process complexities of everyday teaching performance, granting a “view from a [teaching] body.” |

|

|

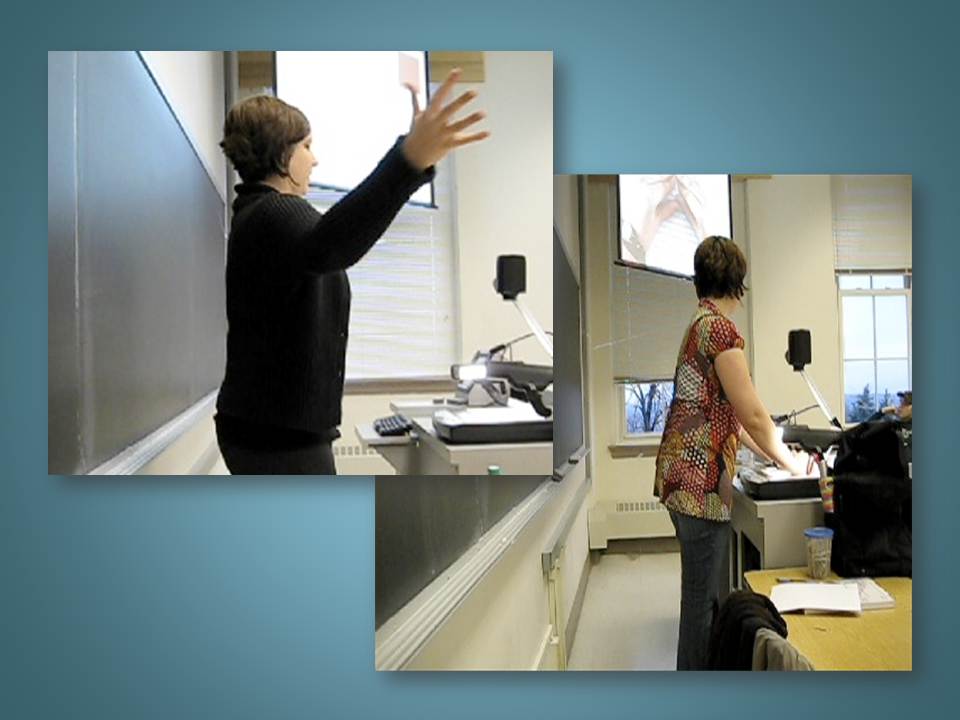

It was indeed a “view from a body” that inspired my response to Laura’s multimodal assignment. I decided to video-record two 50-minute teaching sessions in order to see what I looked like in front of the class with a general interest in my body and its gestures. Using video recordings for teacher review and reflection is indeed a familiar practice in teacher-training, particularly in pre-service teacher education programs (see, e.g., Brophy; Clarke). However, insights into my body as performative mode may not have been gained from merely watching raw video footage and reflecting on it. It was only through the experimental process of multimodal composing that I was able to render and then analyze my teaching as performance: pausing the video, rewinding and forwarding it, watching it with sound off, sound on, moving the image in slow motion, extracting and deleting stills, and stretching, cropping, and fitting images into the format of a PowerPoint slide (stills from the video are featured in the right margin). These composing experiments became the “semiotic resources” (Shipka, “Multimodal”) that allowed the embodied dimensions of my teaching practice to emerge. As I began to play around with the raw footage, my goal became to demonstrate through images how my body was contributing to meaning and to isolate places where it became part of instruction. I shared these stills isolated from the video with my TCW classmates in a series of powerpoint slides. |

|

|

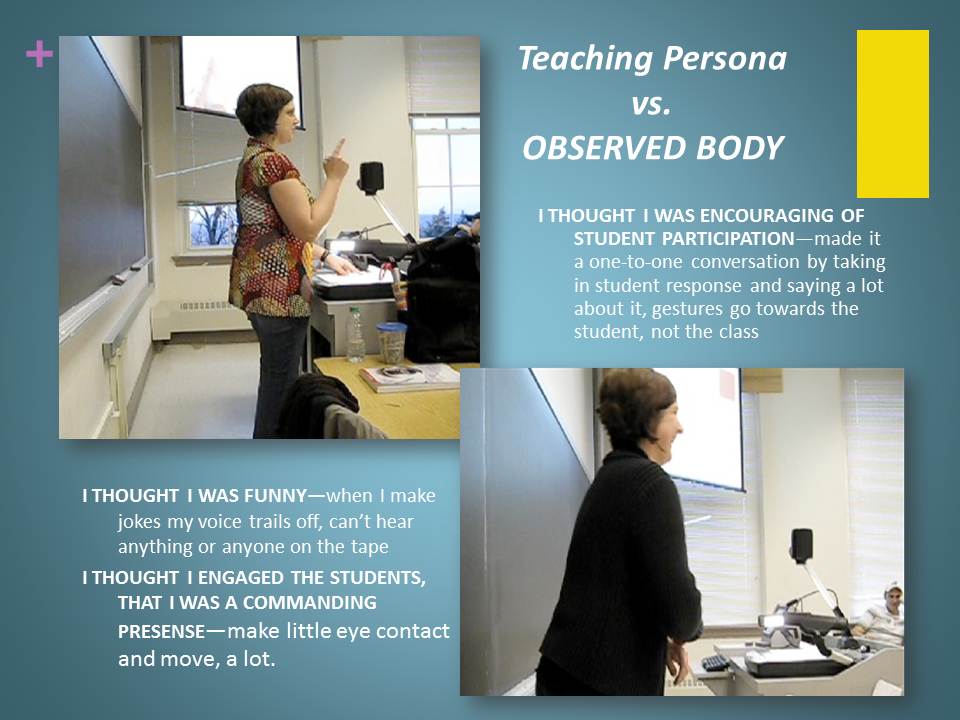

My multimodal work highlighted the in-progress nature of teaching, allowing me to suspend myself in action, frame-by-frame, effectively constructing my embodiment as a tool for study, reflection, and ultimately for editing. Watching myself, I experienced moments of productive dissonance between my physical embodiment and my more abstract self-fashioned identity as teacher. For example, as illustrated in the final interpretive slide (see figure 2), I experienced dissonance between my sense of self as discussion facilitator and an actual act of facilitation. Going into this project, I thought myself to be skilled in leading students in discussion. Drawing from my “view from above” (Conquergood 146), I implemented strategies for moving classroom conversation that I had learned in my teacher-training courses. I knew to remain neutral towards comments, write down student responses on the board, and speak minimally between comments in order to respect and honor students’ contributions. And while I did see myself enacting some of these strategies, overall, my body language challenged my supposed philosophy of leading discussion. I spoke much more than I thought I had, and often directly back to the student who had contributed. Also, as I slowed the video down, I was able to see that my hands gestured directly toward the contributing student, physically cutting the rest of the class off from the conversation. Essentially, my embodiment of leading discussion conflicted with my abstract sense of my teaching identity. This dissonant moment, among others, made me realize the value of “knowing that is grounded in active, intimate, hands-on participation” (Conquergood 146) in my development as teacher.

figure 2 In teacher-training, knowing often begins from a theoretical, distanced view as we read “about” teaching practices and histories. This academic engagement with text and theory is often absorbed into novice teachers’ senses of self, as we find resonance with certain pedagogical schools and accepted practices. But my “view from the [teaching] body” presented me with a different way of digesting theory as a novice teacher, as my ways of knowing became not merely advice-centered, abstract, or cautionary, but embodied. Viewing teaching as performance then grants us an embodied orientation to theory that is grounded in the pursuit of in-practice knowing. Moreover, in understanding teaching as performative, the dissonance between an abstract sense of self and embodied action becomes productive for reflection and inquiry: rather than claiming a coherent teacher identity, we can study teaching as a set of discrete acts that hold open the possibility of transformation in any given moment. Through the dramatization provided by slow motion review of my image for the purposes of critical observation, I came to understand teacher identity as that which literally happens over time and in frames, through movements, gestures, and vocal repetitions and rituals. As novice teachers, how we experience being the body at the front of the class can be transformative. Amidst the many practices, exercises, philosophies instilled in us as new instructors, the way it feels to be the body at the front of the class is often left unexplored. In rendering the physicality of teaching performance through the discovery, play, and in-progress quality made possible by multimodal composing, this project also implicitly asks us to consider a wider range of modes for teacher research. Engaged initially with video recording, images, arrangement, and the use of technology, my project developed without acknowledgment of perhaps its most central communicative technology and significant mode—the body itself. As Jody Shipka aptly describes in her recent article, multimodality has been quietly equated with digital, web-based, or screen-mediated texts. Concerned about the limitations for textual production imposed by this association, Shipka reframes the understanding of multimodality, more broadly describing it as “how multiple modes operate together in a single rhetorical act and how extended chains of modal transformations may be linked in a rhetorical trajectory” (“Negotiating” W347). Thus, within this screen-mediated picture of the teaching body emerges the body itself as a modality, a meaningful and dynamic communicative technology central to the rhetorical trajectory of everyday teaching performance.

|