Online Instructional Technology and Digital and Multimodal Student Composing

While best practices in the field have long advocated for a pedagogy-before-technology approach to the teaching of computer-based writing, purposeful choices about technology should still be an essential consideration in the development and practice of teaching writing online. Several questions in the survey sought to investigate the role technology played for faculty in their instruction and for students in their digital and multimodal composing activities. As with earlier sets of survey responses, there was a wide range of experiences and perspectives. Although some participants seemed pedagogically invigorated by learning new technologies or clearly had prior experience making use of LMSs, digital communication tools, and multimodal instructional technologies, a small set of respondents seemed to have less interest in exploring possible digital affordance for themselves and their students. Taken as a whole, these findings can help us to take stock of current instructional technology use in OWI and to identify where and how we might encourage and support pedagogically thoughtful integration in the future.

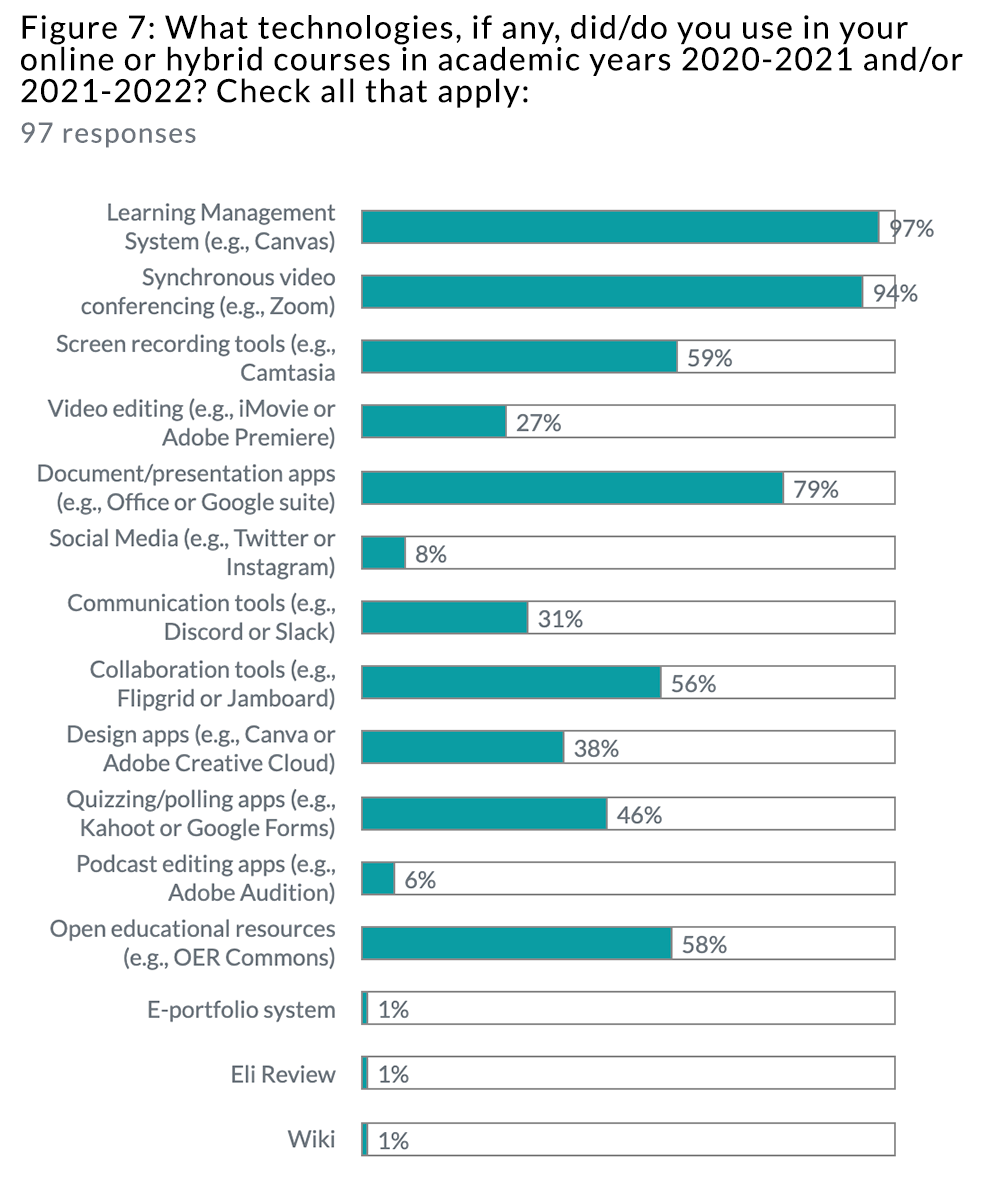

Findings in this theme are drawn from four questions that asked participants about technology they used for instruction and/or asked students to use for composing. In relation to their instruction, responses to question 24 (figure 7) included learning management systems (97%), video conferencing software such as Zoom (94%), presentation and document applications such as those in the Microsoft Office and Google suites (79%), and collaboration tools such as Jamboard and Perusall (56%).

Findings in this theme are drawn from four questions that asked participants about technology they used for instruction and/or asked students to use for composing. In relation to their instruction, responses to question 24 (figure 7) included learning management systems (97%), video conferencing software such as Zoom (94%), presentation and document applications such as those in the Microsoft Office and Google suites (79%), and collaboration tools such as Jamboard and Perusall (56%).

More than half of respondents (58%) also incorporated open educational resources (OER) into their curriculum, reflecting a desire to make materials easier to access and lower/no cost for students. While many respondents noted in an earlier question (21) that they were already “tech-savvy” or that they focused more on issues of pedagogy or classroom equity, nearly a third reported that technology-specific support was invaluable in their preparation. In part, this seems to have been the result of the system-wide switch to Canvas, but many other comments focused on learning new applications for producing instructional content, responding to student work in multimodal ways, and inviting greater digital interaction among students.

In investigating the kinds of technologies instructors asked students to use, the majority of participants (61.9%) reported requiring students to use specific technologies for composing digital or multimodal assignments. When prompted to “say more about the digital/multimodal composing work you ask(ed) students to complete,” (question 26) the 62 responses yielded a diverse array of technologies and projects. While the common inclusion of word processing and presentation software and campus LMSs was unsurprising, participants also highlighted having students compose videos, podcasts, websites, blogs, infographics, digital stories, memes, comics, and more. In naming specific applications, several instructors utilized the newly available system-wide access to the Adobe Creative Cloud/Creative Express suites. For many respondents, this seemed to be a continuation of assignments and classroom activities they had done in-person prior to the pandemic (e.g., “video presentations, but I did this before COVID”). For others, however, it is evident that they were exploring how to incorporate new affordances, literacies, and tools into their curricula at a distance. Some comments cited new videos or live Zoom presentations they created to demonstrate applications they had learned in their own professional development workshops. Others mentioned creation of new multimodal projects they developed which asked students to incorporate images and other modalities documenting life during COVID.

When asked about the kinds of pedagogical or technological support instructors offered if they required students to compose digital/multimodal projects, participants again noted a variety of approaches. This spectrum ranged from completely hands-off (“They could use any software they wanted because I feel like the offered software was too unwieldy to teach”) to very hands-on (“I offer… live & recorded demonstrations, links to video tutorials, written documents created by me, and one-on-one help if necessary”). Most respondents noted providing some kind of instructional support via in-class Zoom demonstrations, step-by-step instructions they created as written text or videos, YouTube links, sources shared in professional development workshops, and/or application “Get Started” materials. One-on-one help via screen-sharing of projects during office hours was also mentioned frequently. Other instructors reported giving students the option of creating multimodal projects or invited them to use whatever software they already knew how to use but did not explicitly require students to create digital or multimodal projects. As one participant noted, “I didn't want to add another technology for students to learn as we navigated online learning. However, prior to the pandemic I did incorporate more digital/multimodal composing work.”

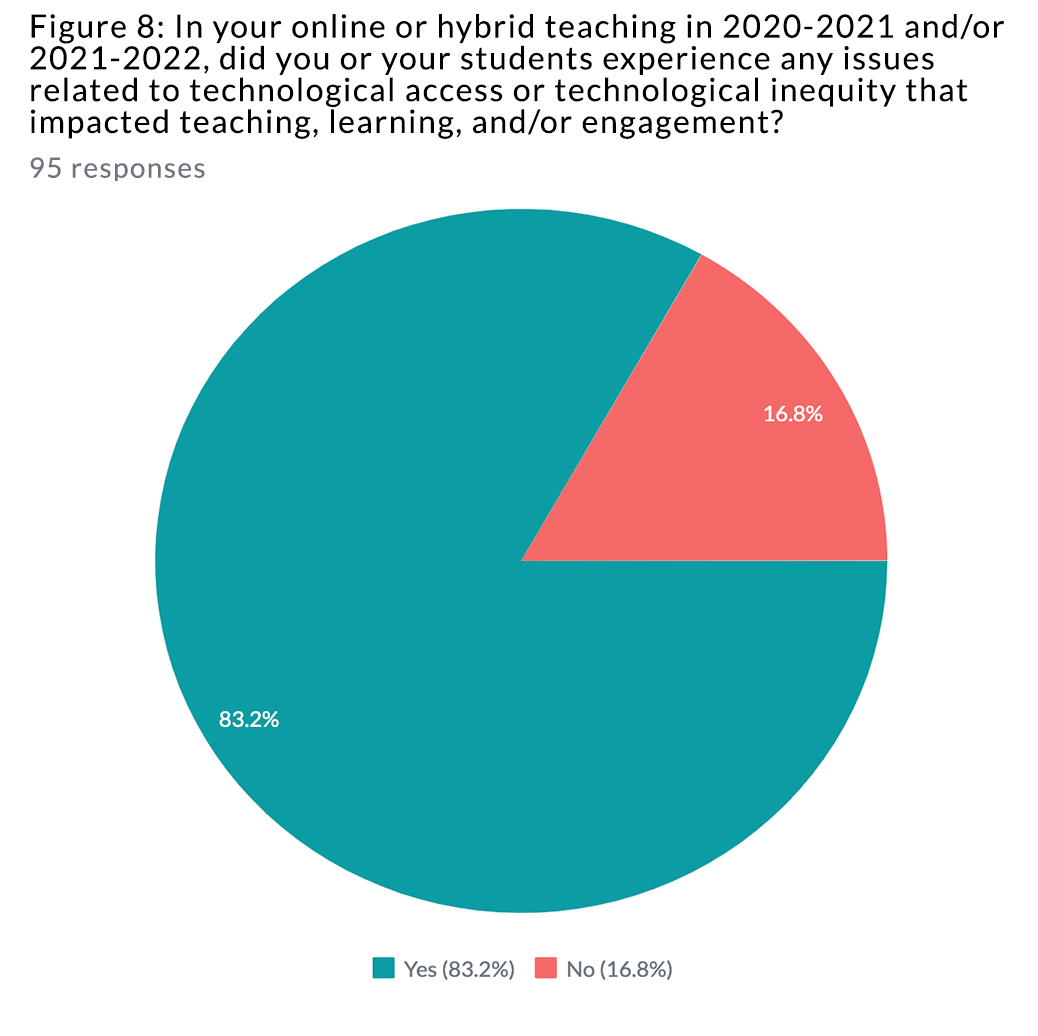

Finally, while integrating digital and multimodal composing technologies has been a focus in writing studies research for decades and can be advantageous for students' rhetorical and literacy practices, not all students (and not all instructors) have the time, hardware, software, or online access to utilize these in an OWI context. As 83% of survey respondents noted (figure 8), technological access and inequity had a significant impact on teaching, learning, and engagement throughout the pandemic. By far, students’ lack of access to high-speed (or any speed) internet was the most frequent issue. Respondents reported students who worked from their cars near free WiFi hotspots, students who shared housing and internet with many others causing instability in connections, and students who simply could not afford to pay for connectivity. Even with the recognition that the pandemic has been an unprecedented time, with students’ returning to familial homes, sometimes in rural, overcrowded, or wildfire evacuation conditions or being required to take on extra shifts as essential workers or care providers for siblings who ordinarily would have been in school, technology access and inequity should continue to be an important consideration in the design of OWI. Notably, all but one participant highlighted important realities that must be addressed to equitably support and expand online writing instruction for all students.

Finally, while integrating digital and multimodal composing technologies has been a focus in writing studies research for decades and can be advantageous for students' rhetorical and literacy practices, not all students (and not all instructors) have the time, hardware, software, or online access to utilize these in an OWI context. As 83% of survey respondents noted (figure 8), technological access and inequity had a significant impact on teaching, learning, and engagement throughout the pandemic. By far, students’ lack of access to high-speed (or any speed) internet was the most frequent issue. Respondents reported students who worked from their cars near free WiFi hotspots, students who shared housing and internet with many others causing instability in connections, and students who simply could not afford to pay for connectivity. Even with the recognition that the pandemic has been an unprecedented time, with students’ returning to familial homes, sometimes in rural, overcrowded, or wildfire evacuation conditions or being required to take on extra shifts as essential workers or care providers for siblings who ordinarily would have been in school, technology access and inequity should continue to be an important consideration in the design of OWI. Notably, all but one participant highlighted important realities that must be addressed to equitably support and expand online writing instruction for all students.

The findings related to this set of responses demonstrate a strong interest among faculty in exploring digital and multimodal affordances for instruction and student composing in online writing courses. Sustaining these technology integrations and supporting continued critical reflection on their pedagogical possibilities will be important work for writing programs. At the same time, attending to student (and instructor) needs and limitations will also be important to ensuring that technological opportunities are inclusive and equitable.