Recomendations and Conclusions

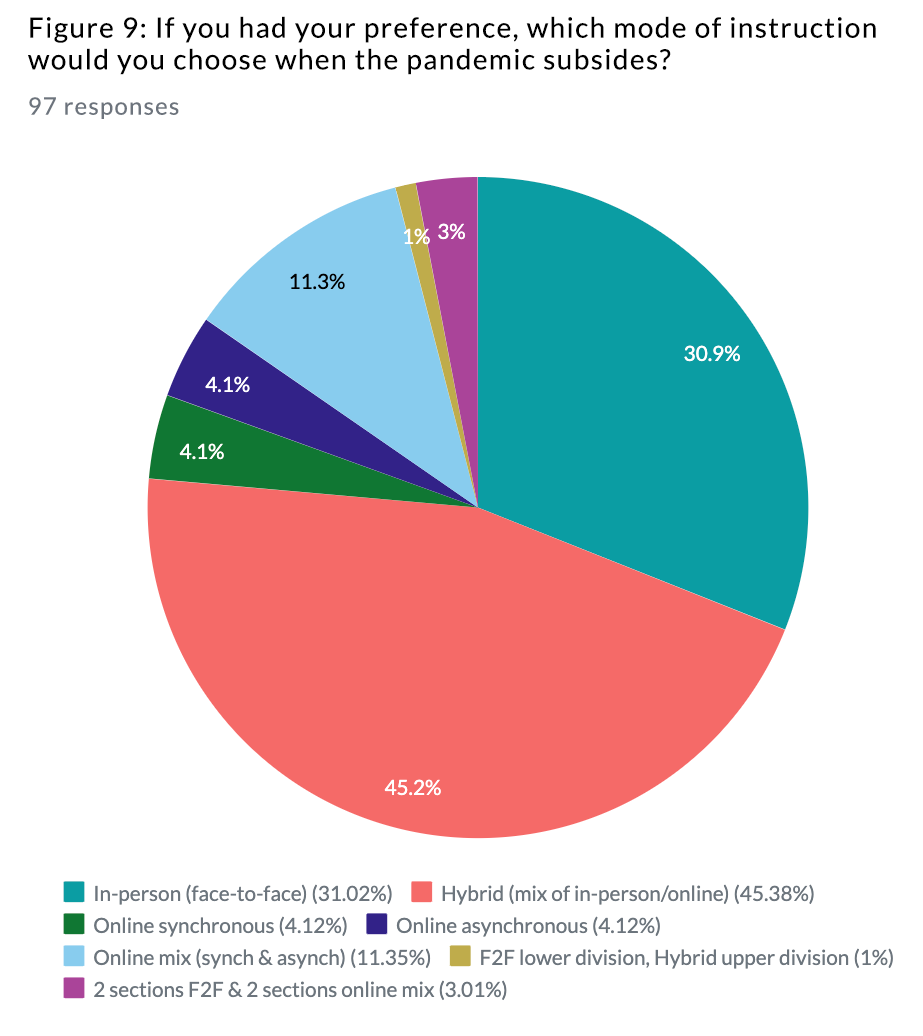

Despite the learning curves and challenges many faced, this survey as a whole documents that instructors find value in the educational potentials of OWI and are committed to developing effective online pedagogies. After nearly two and a half years of pandemic disruptions and experiences teaching writing online, only a third of survey respondents (31%) would choose to return to solely in-person instruction (figure 9). Instead, the majority would opt for some version of online or hybrid modalities if given their choice. Their preferences reflect a spectrum of reasons, including increased flexibility for students and themselves, better attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion, more support of varied learning needs, better ability to leverage technologies and relevant literacies, and new opportunities to explore different approaches to pedagogy and student engagement.

Despite the learning curves and challenges many faced, this survey as a whole documents that instructors find value in the educational potentials of OWI and are committed to developing effective online pedagogies. After nearly two and a half years of pandemic disruptions and experiences teaching writing online, only a third of survey respondents (31%) would choose to return to solely in-person instruction (figure 9). Instead, the majority would opt for some version of online or hybrid modalities if given their choice. Their preferences reflect a spectrum of reasons, including increased flexibility for students and themselves, better attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion, more support of varied learning needs, better ability to leverage technologies and relevant literacies, and new opportunities to explore different approaches to pedagogy and student engagement.

Even with these preferences and firsthand experiences teaching online, many instructors are still developing their OWI practices and learning about the rich scholarship developed in the writing studies field over the last three decades. Reflecting on the survey findings reported here, I conclude by offering several recommendations aimed at helping writing programs support instructors and strengthen their online courses moving forward.

- Develop OWI-specific professional development opportunities. While many respondents reported that campus-wide trainings on LMSs, Zoom, screen capture, and video editing applications were valuable in helping them get started with online instruction, most others commented that such workshops were often too general to be of much use beyond acquiring basic skills. Many emphasized that the technical skills they learned from such initial trainings were just a small part of what is required to design and teach an online course and often focused too much on lecturing and testing that is largely irrelevant to most approaches to teaching writing. Instead, what was often reported as most valuable were department- and program-based trainings, workshops, mentorships, and discussion/working groups. Such professional development and support networks allowed for focused attention on writing instruction, as well as local program/student learning outcomes, uses of technology relevant to student needs and access, department/program priorities, and faculty experience. Moving forward, programs should initiate or expand opportunities for instructors to engage with OWI-specific professional development and experienced colleagues on an ongoing basis.

- Include OWI research and pedagogy in all writing studies graduate education. Given the significance in these survey findings of discipline-specific training for existing faculty, graduate programs should also prioritize inclusion of OWI theory and pedagogy for graduate students working to enter the profession. Without such attention during their graduate careers, TAs (and future faculty) may gain expertise with strategies for structuring a course in an LMS or using specific software through access to centers for teaching or IT departments. However, they might not be prompted to evaluate writing-specific issues such as different online or multimodal affordances for providing feedback on student writing or pedagogical strategies for encouraging student engagement in discussions and peer reviews. These are integral parts of writing instruction that may look different in online, hybrid, and in-person spaces and it behooves the discipline to prepare graduate students to learn how to teach well in a variety of modalities before they enter the profession.

- Focus on pedagogy first but attend to digital tools and multimodal composing too. There are a couple take-aways from these responses for thinking about future OWI academic training with graduate students and professional development with faculty. First, technology comfort and experience exist along a continuum. Although they have been around for more than two decades and widely used for at least 10 years, not everyone utilized a campus LMS prior to the pandemic. While some in the past have opposed their use on the grounds that they surveil students or that they add an extra, unnecessary layer to teaching preparation, an LMS provides access for students to course materials on demand. More than just housing content, however, a well-designed LMS course can offer a roadmap, scaffold content, and prompt students to stay on track with assignments. There is both a pedagogical design component and a technical component that should be part of any OWI training.

Second, while an LMS often provides the backbone for an online course, survey responses highlighted many other technologies for interaction, communication, and community building that can be essential to an innovative, productive learning experience. Incorporating demonstration and discussion of the affordances and constraints of tools instructors are using, in direct relation to pedagogical goals and student needs, should be a component of OWI professional development.

Finally, incorporating digital and multimodal composing technologies into online writing courses offers opportunities for students to develop valuable critical, multiliteracy, and professional practices, just as it does in in-person classes. Being online can present additional challenges to access and support from instructors, but there are also instructional affordances such as being able to create and re-use digital tutorials and to screen share during one-on-one help sessions that can be an advantage in teaching in an online context. Learning how to integrate composing technologies in ways that are pedagogical, not just technological should be modeled and developed for those new to OWI. As Griffiths et al, (2022) found, too often “resources provided to faculty” have tended to emphasize “‘use of’ versus ‘teaching with’ technology,” leading to too many instructors focusing on technologies themselves rather than letting pedagogy drive. (66).

- Recognize and compensate for professional development labor. While local initiatives are invaluable in tailoring OWI-specific professional development, they also require significant amounts of labor for those who lead or attend these activities. Representative of some sentiments from the survey, are comments about a lack of compensation for participation, institutional barriers that prevented some instructors from having access to training, and extra workload on faculty with prior online experience who were asked to support others one-on-one.

Faculty who develop and share OWI-specific expertise with colleagues, organize and create materials, and spearhead the maintenance of interest and momentum to keep up with changes should be recognized and compensated. Engagement in continued professional development by instructors of all professional ranks requires time and effort that may be particularly in short supply where heavy teaching loads are common. In both types of involvement, labor should be recognized in faculty evaluations and assigned course loads, and faculty should be compensated financially for their time where possible.

- Support opportunities to access best practices, resources, and disciplinary scholarship. Many respondents utilized and benefited from resources external to their campuses such as the Online Writing Instruction Community’s symposiums and GSOLE’s conferences and webinar series, certification courses, and Online Literacies Open Resource (OLOR). Departments and writing programs should encourage instructor engagement with these discipline-specific sources of OWI professional development. OWI research has also become a staple in many writing studies conferences at the local, regional, and national levels and again departments and programs should work to incentivize and support access for all faculty regardless of professional status. Although institutional financial resources are not always inclusive of non-tenure track faculty, writing programs, departments, and WPAs should prioritize advocacy for such compensation for all OWI faculty, particularly if there are initiatives to expand online course offerings. Further guidance on this issue can be found as one of the key tenets in GSOLE’s online literacy instruction (OLI) statement.

- Offer choice in course modality for instructors and students. Based on qualitative survey comments regarding course modality preferences, choice is a key component of teaching and learning success and satisfaction for instructors and students alike. While it is not always possible to accommodate all preferences, placing instructors in course modalities that play to their teaching strengths and that are attentive to real-world working conditions and personal needs benefit all. Similarly, students have varied learning, personal, and professional needs that are better suited to differing classroom modalities. Working to offer instructional options that are more flexible can support diversity, equity, inclusion, retention, engagement, and academic success for both students and faculty.

- Attend to student (and instructor) technology access and equity. As this survey found, nearly all instructors experienced access and equity issues related to technology among students in their online classes. Further, given the working conditions within the field and higher education more broadly, not all instructors were/are provided with adequate (or any) technology required to do their jobs in a digital environment. Although technology seems to be readily used by and available to all, our pandemic teaching experiences demonstrated this is far from the case. Despite the efforts of universities to provide rental/loaner laptops and free WiFi to students in need, stable internet connections, broken cameras and mics, use of mobile phones for coursework, lack of access to specific software, and a host of other technology issues caused (and will continue to cause) major disparities in educational experiences. While the teaching of writing must continue to evolve to be inclusive of multimodal and digital literacies, it also needs to be mindful of student and instructor realties. Use of technologies should always fit programmatic learning outcomes, be free or low cost, and attend to students’ access via both WiFi connections and the device types/capabilities on which they work.

- Continue to engage in and support OWI research. It is important to document OWI experiences during the pandemic because it sets a benchmark for what happened during this tumultuous time. Never has there been such a large-scale implementation of online instruction and teaching experiences ran the gamut. We can only improve and build on instructional approaches by first understanding what the challenges and successes were. Even when we finally reach the post-pandemic times, the practices of OWI will still need continuous assessment, reflection, and iteration into the future. As GSOLE’s OLI principle 4 outlines,

-

OLI-related conversations and research efforts are the province of all of those involved in OLI, whether these are occurring within or across institutions and/or disciplines. This broad and diverse group has a stake in advocating for the effective preparation and development of all OLI-related instructors, support programs, tutors, and students… As a cornerstone to promoting and working to maintain the ultimate integrity of any OLI initiative (from course development, to program building, to the allocation of resources), OLI administrators, instructors, and tutors should be committed to ongoing study of, research about, and exploration into OLI. (GSOLE)

-

This survey captured a reflection of instructor experiences with OWI two years into the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants’ divergent perspectives reveal a complex educational context where teaching and learning have been impacted by an unprecedented global health crisis, institutional working conditions, and the affordances and constraints of our technological and pedagogical abilities. While hardly an ideal situation given the unexpected transition, we can learn much from this historical moment about utilizing online and hybrid modalities to teach writing and support student learning. By reflecting on the challenges, success, and adaptations experienced across this diverse state university system, we can continue to evolve approaches to OWI that are accessible to and inclusive of all students and instructors.