Preparation and Professional Development for Online Writing Instruction

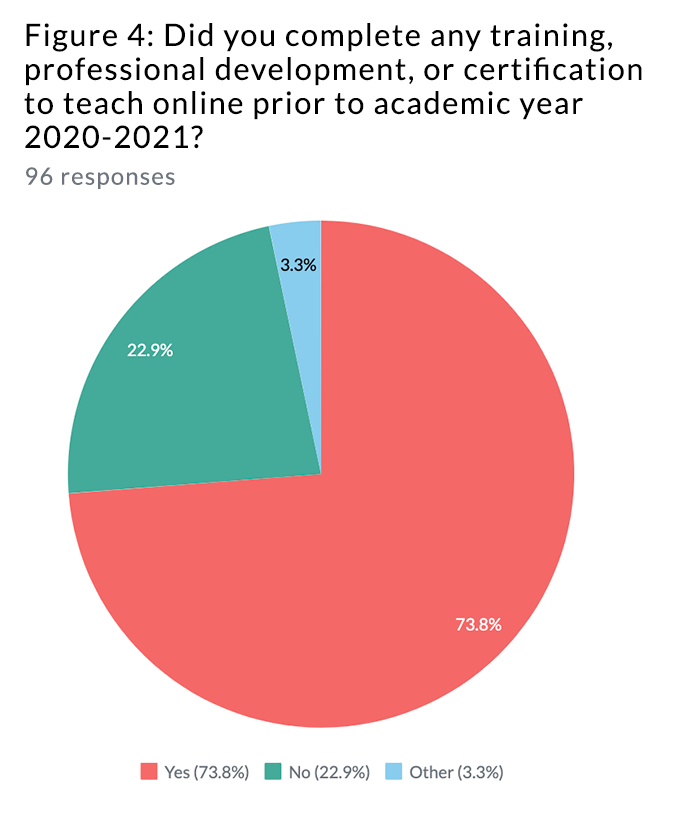

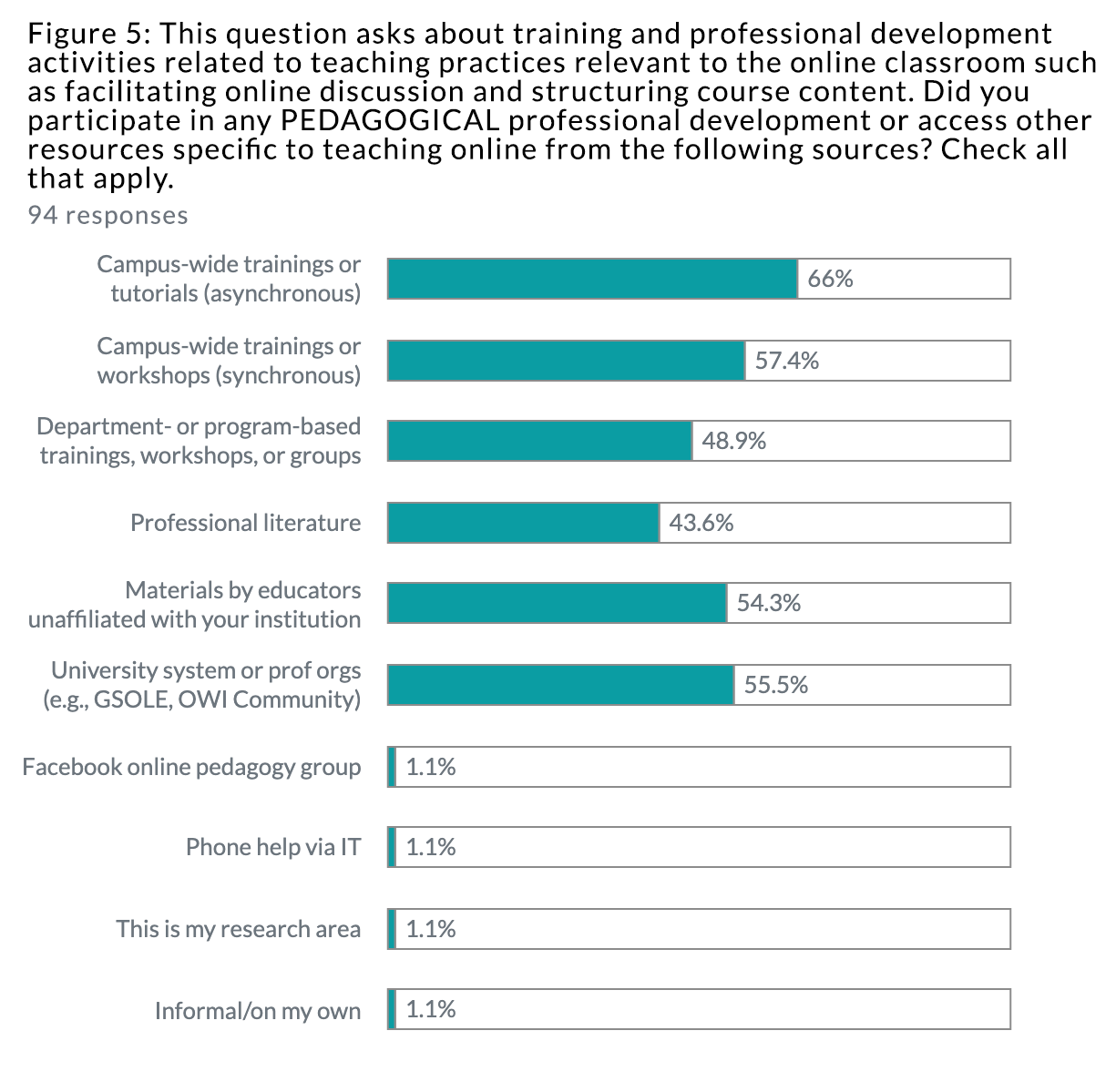

To investigate and assess how instructors prepared for their transition to online instruction, section three of the survey asked a series of seven questions investigating the sources, foci, preferences, and perceived effectiveness of respondents’ preparation for OWI. Nearly 75% of respondents (figure 4) participated in some form of training prior to teaching online in academic year 2020-2021. Instructors accessed support and professional development from a variety of sources and in a variety of modalities (question 18, figure 5), including from their departments/programs, their own campuses, and the statewide university system, as well as from professional literature and organizations. While many reported that this support was invaluable for the fully online year, others had mixed or poor experiences. This section of the article discusses key findings related to training and professional development for OWI.

To investigate and assess how instructors prepared for their transition to online instruction, section three of the survey asked a series of seven questions investigating the sources, foci, preferences, and perceived effectiveness of respondents’ preparation for OWI. Nearly 75% of respondents (figure 4) participated in some form of training prior to teaching online in academic year 2020-2021. Instructors accessed support and professional development from a variety of sources and in a variety of modalities (question 18, figure 5), including from their departments/programs, their own campuses, and the statewide university system, as well as from professional literature and organizations. While many reported that this support was invaluable for the fully online year, others had mixed or poor experiences. This section of the article discusses key findings related to training and professional development for OWI.

The most salient finding from section three responses as a whole is that there was no one-size-fits-all approach to effective professional development. Given the diversity of prior teaching experiences (0-31+ years), disciplinary backgrounds (only 35% had academic specializations in composition and rhetoric), and extraordinary teaching workloads experienced by many, respondents tapped into and appreciated options in the kinds of training they received, including options for modalities and facilitators.

Related to the finding that there was no singular approach that worked for all, participants (89 responses to question 21) spoke to a wide range of training and professional development experiences. In coding responses to this open-ended question about the most helpful sources, methods, and subjects of professional support, six categories emerged:

- Training and support related to learning management systems (LMS)

- General technical instruction and support for specific platforms and applications (e.g., Zoom, Google suite, Perusall, Annotate Pro, Jamboard, etc.)

- Pedagogy-specific training for the online classroom (e.g., collaboration, student engagement, community development, active learning, equity, inclusion, anti-racist pedagogies, etc.)

- Course design support focused on accessibility and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) strategies

- Variety in where/from whom instructor training and support were offered (e.g., campus IT departments, campus teaching centers, departments, professional organizations, etc.)

- Flexibility in how instructor training and support were offered (e.g., synchronous webinars, asynchronous courses, regular meetings through writing programs/departments, one-off workshops, etc.)

As these six categories suggest, there was a wide variation in the training and support available to instructors in summer 2020 and during the following two academic years. Qualitative responses highlighted everything from one-off presentations, one-on-one IT support, and weeks-long synchronous and asynchronous campus-wide courses, to required campus certifications and elective workshops offered by disciplinary organizations.

Although it came in many forms, approximately a quarter of respondents (question 21) commented that the best support they had came from colleagues either through formal department or writing program presentations or through regular online meetings to share experiences, approaches, and materials with colleagues in their disciplines. As one survey participant noted, “The most helpful resource for me was the support and experience provided by colleagues. Meeting with them to discuss everything from structuring Canvas pages to utilizing new online tools was a life saver.” Similarly, another participant wrote “workshops developed and delivered within my department by writing studies faculty” were the most beneficial because “the relevance and specificity were immediately useful.” Still another highlighted their “English Department's Composition Faculty series,” writing that it was “helpful in that it met weekly over Zoom and allowed composition faculty to discuss online instruction with fellow writing faculty.”

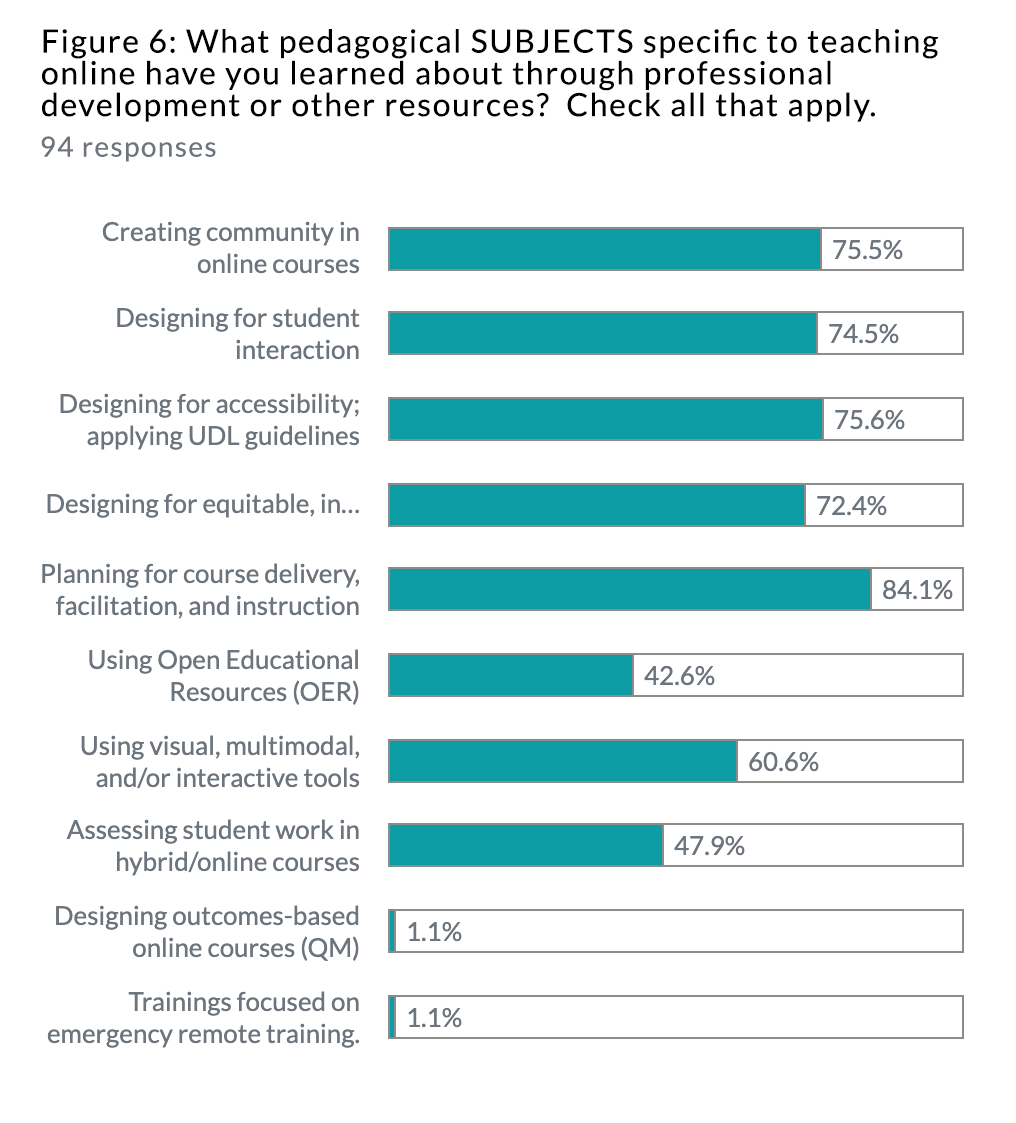

In considering the subject matter of survey participants’ professional development opportunities (question 19, figure 6), campus centers for teaching were also highly regarded. Not all support was specific enough to the teaching of writing for some, but centers often covered important issues related to class engagement, accessibility, UDL, and structuring courses. As one respondent noted, “The trainings led by our Center for Faculty Development were well done and thoughtfully developed, though they were not discipline-specific, which made them helpful but limited.” A substantial number of participants reported that during the pandemic they were concerned not just with the technical logistics of moving courses online or to hybrid modalities, but also with focusing on pedagogical issues and student equity concerns, particularly those related to creating community, using OER materials, and utilizing anti-racist pedagogies. Such professional support came from both department/writing program initiatives and centers for teaching. As one respondent wrote, “My institution offered a training in creating equity in an online learning environment that was really eye-opening and helped me think more deeply about anti-racist and inclusive practices for building community and supporting students in their work.” Similarly, another noted that their campus’ “OTL (Online Teaching Learning) and JEDI PIE (Justice, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion - Pedagogies for Inclusive Excellence) helped…the most.”

In considering the subject matter of survey participants’ professional development opportunities (question 19, figure 6), campus centers for teaching were also highly regarded. Not all support was specific enough to the teaching of writing for some, but centers often covered important issues related to class engagement, accessibility, UDL, and structuring courses. As one respondent noted, “The trainings led by our Center for Faculty Development were well done and thoughtfully developed, though they were not discipline-specific, which made them helpful but limited.” A substantial number of participants reported that during the pandemic they were concerned not just with the technical logistics of moving courses online or to hybrid modalities, but also with focusing on pedagogical issues and student equity concerns, particularly those related to creating community, using OER materials, and utilizing anti-racist pedagogies. Such professional support came from both department/writing program initiatives and centers for teaching. As one respondent wrote, “My institution offered a training in creating equity in an online learning environment that was really eye-opening and helped me think more deeply about anti-racist and inclusive practices for building community and supporting students in their work.” Similarly, another noted that their campus’ “OTL (Online Teaching Learning) and JEDI PIE (Justice, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion - Pedagogies for Inclusive Excellence) helped…the most.”

When asked about training and resources that were least helpful, many participants (51% of 78 responses to question 22) indicated that the trainings provided by campus IT departments and the university system that focused on LMSs, Zoom, and other specific technologies were useful in the development of course structures and mechanics, but less so with developing online pedagogies. The initial need for these resources was acute on several campuses that underwent a pre-planned transition in LMS from Blackboard to Canvas during the pandemic. However, overall participants saw limited value in these trainings given their broad, decontextualized focus that was often geared toward large, lecture-based and testing-heavy courses. Some described these resources as “too general/basic, and not readily applicable to the writing classroom.” Others took issue with the “focus on tools to prevent plagiarism, like Proctorio,” writing that they were “a waste of time when they are not given timed writing assignments. The iterative process of writing inherently prevents most plagiarism. Also, the focus on administering multiple choice exams online is a waste of time.”

In contrast, respondents seemed much more satisfied by engaging with disciplinary experts in composition broadly and online writing instruction specifically. Multi-day symposiums, ongoing webinar series, and just-in-time online resources offered by organizations such as local affiliates of the National Writing Project, the Global Society of Online Literacy Educators (GSOLE) and the OWI Community were frequently cited as vital resources. Several respondents reported that these experiences were “invaluable when thinking about writing instruction in an online space” and more relevant than some of the campus technical trainings that felt like they were “sometimes written more for an IT person, not a typical writing instructor.”

Finally, respondents expressed strong opinions about the modalities in which they accessed training and professional development. While a few participants appreciated the flexibility of asynchronous courses and resources (“Asynchronous training videos from colleagues and organizations worked best because I could do them as needed and in my own time.”), the majority preferred synchronous interactions where they could learn, ask questions, and share approaches in real-time. Comments such as the following are representative of which kinds of trainings were reported as working best: “Synchronous online classes;” “Co working with others doing the same work at the same time;” and “Trainings where I could interact with humans to learn, gripe, and ask questions.” Although the preference for synchronous interaction may have been in part a reflection of the isolation many felt during the pandemic (“I am tired of being alone in my apartment” wrote one respondent), the majority of sentiments were focused on the value of community interaction, pedagogy, and practical problem solving relevant specifically to the writing classroom.

Findings in this section of the survey confirm the value of discipline-based training and professional development. OWI-specific training and active engagement with online writing experts and experienced colleagues helped instructors to reconsider their pedagogies and course designs for teaching in online modalities. While some teaching center and campus IT training was important, particularly for those completely new to online teaching and the integration technologies in the classroom, this was often less useful beyond basic introductions to a changing LMS and shifting to a module-based course structure. Taken as a whole, participant responses demonstrated a need for flexibility, variety, and inclusion of experienced OWI faculty to support instructors’ new and ongoing pedagogical, technological, and practical needs.