Quantitative Based Surveys

During the course of this study, I interacted with four Journalism courses at a large urban university. Journalism classrooms were selected as a focal point as a result of professional journalists’ acceptance of Twitter, thus hopefully leading me to a larger number of students engaged in the social media platform. As Farhi (2009) notes, “News organizations and reporters have been quick to adopt Twitter for an obvious reason: Its speed and brevity make it ideal for pushing out scoops and breaking news to Twitter-savvy readers” (p. 28). Journalists on Twitter often link to their own stories, follow each other to find out news, share important pieces of information, and much more. With this in mind, it was my hope that students in the Journalism classes were more likely than students in other disciplines to have, at the very least, heard of Twitter and tried it out.

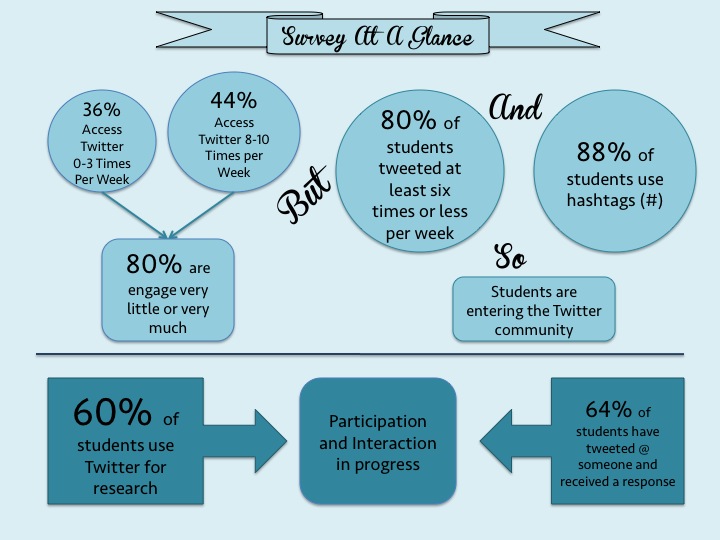

From the quantitative data, a number of observations can be made. Students either tended to access Twitter very little—36% access the site 0-3 times per week—or quite a lot—44% access the site 10+ times (See Figure 6). This suggests that students are either markedly unengaged or they are highly engaged. There is little middle ground by comparison. It is difficult to assess if it is more likely for a student to use Twitter than to not use Twitter since the data is relatively close (36% versus 44%). However, the difference between the two extremes of use (a combined 80% of people use it a lot or use it a little) and those who use it nominally (20%) is relevant. It seems that Twitter leaves little middle ground; students are either fully entering Twitter’s activity system or are engaged very little—at least in terms of accessing their Twitter feed. Therefore, students either perceive Twitter as a decidedly effective tool to accomplish an object/motive within the activity system in which they use it, or they perceive it as an ineffective tool. This leads to the possible conclusion that Twitter as a tool either resonates very well with students or they dislike it, do not understand how to use it, or have never used it.

Additionally, there was also little statistical relation between the number of times students accessed the site and the number of times students tweeted. The majority tweeted 0-3 times (48%), followed by 4-6 times (32%). This means that 80% of the students tweeted 6 times or fewer throughout the week. Not only does this show little correlation with students that accessed the site 10+ times per week, it also means that there was little correlation with students that accessed the site 0-3 times. In other words, regardless of how many times students accessed the site, they were still entering into Twitter conversations and communities. Individuals or organizations within other activity systems (utilizing Twitter as a tool to accomplish their goals) create dialectic conversations and communities (Gillen and Merchant, 2013). Since activity systems are “dialectic” (Russell, 1995, p. 55) and “mutually dependent” (Kain & Wardle, 2006, p. 2), participants who use Twitter influence the overall activity system of Twitter through their tweets and—however indirectly—also influence any other activity system also connected to Twitter. This is partially supported by the use of hashtags (#). The vast majority of students, 88%, use hashtags to some degree. However, 56% of these reported using it only “Sometimes.” While it is also possible that they are not using hashtags to their full potential, this suggests that these students are already willing and able to enter into community discussions and interact with the world. Both tweets and hashtags allow students to socially exchange and distribute their ideas (Engeström, Learning and Development, 1987). Entering into communal conversations also helps students “development (reconstruction) of individual agency and identity [via] expanding (or refusing to expand) involvement with an activity system by appropriating its object/motive, which requires the appropriation (and sometimes transformation) of certain of its genres” (Russell, 1997, p. 534). Students are therefore incrementally changing the activity system of Twitter while gaining identity and agency and learning how to be most effective in the genre of “public discourse” (Russell, 1995, p. 63).

Figure 6. Students' use of Twitter

The next set of data offered contrasting views as to why students were accessing the site. With regard to whom the students followed, 44% followed celebrities, 28% followed friends, 24% followed journalists, 12% followed brands, and 28% were not applicable because they did not answer the question correctly. Following celebrities, friends, and brands to a high degree might insinuate that students’ view of Twitter is that it is a social and not academic tool. But because activity systems are in a constant state of change and participants are continually appropriating “tools and object(ives) and points of view of others” (Russell, 1995, p. 55), it makes sense that students would follow both particularly influential participants (celebrities) as well as those that are involved in activity systems in which they have an interest (friends/journalists). If change occurs to the activity system as a result of a celebrity, participants are able to react to the change or incorporate it into their interaction with the site.

When this data is set in relation to the next two questions concerning the use of Twitter for research, the picture significantly deepens. The majority of the students, 60%, use Twitter for some sort of research activity, thereby supporting the potential of Twitter as a place to gather and share information. In fact, the relevance of students using Twitter as a place of research would be important if even only a small percentage used it for this purpose. This shows that Twitter is a source for potential academic material and this potential could be cultivated. Students are willing to use the site to connect with activity systems for information about subjects they are interested in. The mere fact that the majority of students have already used Twitter for research is quite exciting. Students are already participating with Twitter in meaningful and academic ways.

Additionally, 64% of the students remarked that they had tweeted @ someone they did not personally know and received a response. This information further reveals the participatory potential of Twitter and the interaction between people who might not otherwise be able to connect in a public forum. Because of the format of Twitter, there are low barriers to students connecting with people they do not personally know, and Twitter also facilitates the mentorship process of participatory culture. Not only is tweeting @ the person they do not know relatively easy (and limited in character length), but so is the response.

Based on this data, we can see that students are participating quickly, easily, and effectively with the world through the use of Twitter. It seems reasonable then that with some effort or guidance on the instructor’s part, students would be able to harness the bridge Twitter provides between academia and the broader culture in order to expand their involvement with the world. Not only are they developing the skills discussed by Jenkins et al. (2006), but they are able to enter into the kinds of civic and community conversations suggested by Yancey (2009) and Bazerman (1994). The effect of this is two-fold. Firstly, since students on Twitter are not engaging in subject-producing or instrument-producing activities, they are therefore engaging in learning activity as an activity-producing activity (Engeström, The Structure of Learning Activity, 1987). This kind of learning activity is more elastic than traditional models and therefore more productive. It also ensures that the focus is not on the creation of new subjects for the system, but rather the contributions of the subjects to the system. Students who engage in the participatory culture of Twitter—a culture that reinforces motivation and engagement—do not simply repurpose academic knowledge but rather encounter, interact with, and produce their own ideas. Secondly, Twitter allows students to encounter numerous genres of writing within multiple, and sometimes divergent, activity systems each time they access their Twitter feed. Because students are able to choose who they want to follow, they are also choosing which activity systems in which they want to be involved. This helps them expand into those activity systems and decide what kind of reading and writing they should be doing in order to enter their chosen system (Russell, 1995, p. 538).