Home | Introduction | Case Study 1 | Case Study 2 | Concluding Thoughts | References

Case Study 1:

Avatar Design

The 5e Dungeon Master’s Guide ends its introduction with a simple piece of advice for GMs: "know your players" (Mearls and Crawford 2014). For a novice GM, this seemingly straightforward recommendation only hints at the high-level of interdependence between the Game Master and the players during any given session. As a mannerist-rhetor, a GM’s choices are constantly informed by the ever changing needs, dynamics, and choices of an individual playgroup. This dynamic ecology of play requires many combinations of GM-ly styles, attitudes, improvisations, and approaches to be effective: Do I intricately plan out this evening’s sessions (the deep planning GM) or do I improvise (the improvisational GM)? Should I add more roleplaying or combat encounters? Do I add more puzzles to this quest? Should there be more traps for the rogue to disable? Do I dole out magic items more judiciously or with a looser hand? Should the game have a comedic or dark and gritty tone? These and many other design decisions are answered differently, and often on the fly, based on the mutable composition, attitudes, and playstyles of a playgroup. An effective GM applies a mannerist approach by considering these factors in addition to the kairos of play in order to design, implement, and ultimately entertain through phronetic action.

Knowing your players is equally important for an instructor in a classroom. Effective pedagogy requires that an instructor understand the unique and changing needs, competencies, and learning styles of their students in order to cultivate an inclusive learning community and design a strong curriculum. As with a Game Master, the highly adaptable, style-switching mannerist-approach may be valuable, but how does one quickly learn to know their students/players, particularly in the asynchronous/synchronous environment of a distance learning environment? Here we suggest using avatars as a possible heuristic for understanding student needs, competencies, and expectations and then encourage applying a mannerist approach to instruction and curriculum design as a response. The case studies below examine how avatar/character generation systems could be used to inform curriculum design in online spaces and improve group dynamics in collaborative writing projects.

Case Study 1.1: Avatar Construction, Character Generation, and Roles for Play in D&D 5e

The term "avatar" is derived from the Sanskrit word "avatara" which translates to "a god in earthly form" (Banks, 2015) or "descent" (Waggoner, 2009). In the world of video games, the term avatar has long been associated with the in-game, graphical representation by which players interact with a game environment (Hart, 2017). In the world of game studies, the term "avatar" has been widely contested and explored (see Greene and Figueiredo, 2021) with varying definitions that move avatar far beyond simple representation and consider the ways that players engage in body/mind synthesis and embodiment in a digital world (Alton, 2017; Bogost, 2012). In video games particularly, players’ avatars are a vital connection to their sense of immersion, embodiment, and player agency (Murray, 1997). Players embody their avatar to experience stories and interact with each other in specific ways, and one of the most frequently modded aspects of a game are skins or graphical add-ons to add deeper levels of avatar customization. Games systems such as World of Warcraft (2004) and Dungeons & Dragons 5e (2014) offer players numerous customization options for their in-game avatars. These deliberate design choices for avatar customization—affordances and limitations—raise questions of inclusivity (Fordyce et al., 2018s), performativity (Figueiredo and Greene, 2021), and procedural rhetoric (Bogost, 2010).

Nearly since its inception, Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) and the larger tabletop role-playing genre has been a cooperative, collaborative exercise that necessitates a clear understanding of expectations and roles necessary to facilitate play. As a structure, D&D has two main nodes: that of a Player Character (PC) who embodies a singular character/avatar and the Dungeon Master (DM) who embodies all other characters, develops the game world and the adventure, and facilitates all other aspects of play. Players in D&D are constantly communicating their intentions and expectations through in-game and out-of-game actions; yet it is the DM that often has to respond with rapid modulation and alteration. With a mannerist-approach, a DM can swiftly employ a combination of playstyles, performances, and strategies to make the game successful.

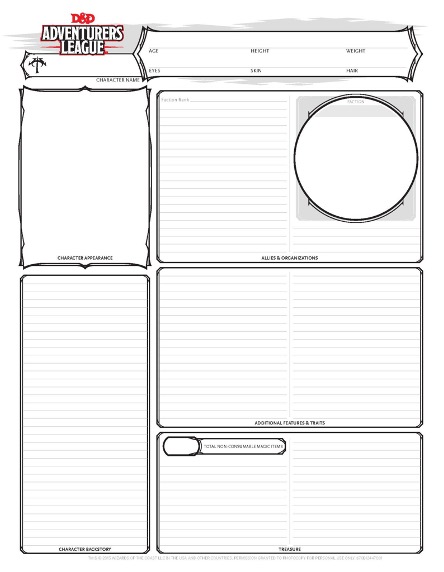

One of the principal ways that a DM reads player intentionality is based on how players develop their characters – the avatar they will embody in the game world. In Dungeons & Dragons, each PC (except for the Dungeon Master) traditionally adopts a single character that they design. They develop this character by first choosing their race (elf, human, dwarf, etc.), class (fighter, rogue, cleric, etc.), and rolling their attributes (strength, dexterity, intelligence, etc.), which will dictate their core competencies in the game world. Players often further develop their characters by describing their physical appearance, writing detailed backstories, and even outfitting their characters with gear and equipment that has both a mechanical and aesthetic effect in the game.

Figure 1: Page #1 of the D&D Character Sheet highlighting race/class choice and attributes.

Figure 2: Page #2 of the D&D Character Sheet highlighting character appearance and backstory.

D&D has long developed the concept of "party composition" or the "balanced" party in terms of character roles within the play group. Mechanically, to varying degrees, D&D has suggested the four-player default group of a fighter, wizard, cleric, and rogue as the "balanced" party necessary to encounter and navigate all aspects of the play experience including (but not limited to) exploration, combat, puzzle solving, and healing. The discrete choices that players make about their avatar functions rhetorically and communicates to multiple audiences: specifically other players in the group and the dungeon master. To the party, avatar choice suggests players’ roles and what should be expected of them collaboratively: Am I a muscle-bound fighter? I’ll be expected to tank the front line and involve myself in combat. Am I a studious halfling wizard? I’ll be expected to sling spells and handle arcane matters. This communication is vital for building a functional group dynamic with intra-party equity.

To the dungeon master, though, avatar choice communicates performance roles and players’ intentions for the adventure, which is important from a design perspective. For example, one way that players signal to the Game Master that they want more combat encounters is to choose an avatar that’s focused on combat (a fighter, paladin, barbarian, etc). More specifically, players may arm their avatar with specific gear that details exactly the kinds of encounters they want – say a greatsword for close-ranged melee or a longbow for ranged combat encounters. In this way avatar design is discursive and the Game Master often responds to this communication with a mannerist approach that privileges reasoning based on a number of factors. As an example, one GM may opt to add more encounters of players’ desired type in order to meet needs and satisfy expectations. Yet another GM may respond by challenging players with a very different type of encounter – one that goes against the strengths of their avatar – such as a ranged monster encounter meant to challenge a melee-focused avatar.

When and how to respond to players’ decisions requires a mannerist approach that plays to the delicate balancing act of being a GM. A dungeon master is first and foremost a narrative and game designer; they are responsible for developing the adventure, planning encounters, and building the story. If the dungeon master’s goal is to provide a satisfying play experience, then considering their players’ avatar choices is always instructive: Does the party have a lot of fighters? Then I’m going to need to design an adventure with a lot of combat. Does the party have several rogues? Then I may have to consider building in more puzzles or traps for them to solve.

Since the avatar composition of a playgroup can change drastically from session to session based upon attendance and other factors, a GM (and by extension an instructor) are constantly taking phronetic action and making adjustments on the fly, requiring a combination of deep planning and rapid improvisation based on many factors that can not be known before the play experience begins.

Case Study 1.2: DPS, Tank, or Healer: Avatar Aesthetics and Group Dynamics in WoW

Tabletop roleplaying games highlight the importance of avatar choice for design and development, but MMOs such as World of Warcraft or WoW (2004) show the role of avatar selection and customization in a mannerist approach to player grouping and party composition. For an MMO with PVE (player-versus-environment) and PVP (player-versus-player) challenges, balanced group or party composition is vital to completing in-game tasks and acquiring rewards. Players in WoW complete in-game content such as dungeons, scenarios, and instances as groups (sometimes called raids). Within these groups, players’ jobs are dictated mechanically by three overarching roles: the DPS (damage per second), tank, and healer.

In broad terms, the tank absorbs damage (damage mitigation) from monsters, the DPS (or damage dealer) deals the damage, and the healer adopts a vital support role by healing players. Missing one of these elements can mean the difference between failure and success when it comes to completing in-game content and going on raids.

Much like D&D 5e, WoW players determine their "roles" through avatar/character creation when they decide upon their players’ race and class. They then build out their character progressively through leveling and the gear they receive as rewards for in-game accomplishments. Party composition becomes an important aspect of the game once players engage with in-game content in groups.

In the early days of WoW, players grouped up manually to meet challenges and overcome in-game content. This process developed organically in the game world, where players, as their avatars, stood in public game locations and communicated through chat about their intentions for "raiding" or the needs of the groups. Groups then formed naturally through a player-mediated, mannerist-approach that considered the unique situation and challenges of the moment rather than an algorithmic method.

Players would advertise their needs and capabilities verbally, textually, and through avatar choice; in early iterations of WoW, player roles could be readily identified simply through the visual aesthetic of their gear. Tanks, for example, wore specific armor sets that have in-game mechanical advantages for their class, making their role obvious to veteran players simply based upon gear aesthetics. Additionally, the aesthetics of a gear set could also denote the veterancy and experience of a character since only certain items, gear sets, and/or designs could be attained by completing specific dungeons and other in-game content.

Figure 3: WoW Class/Race Selection Screencapture.

Figure 4: WoW Character Customization Screencapture #1.

Figure 5: WoW Character Customization Screencapture #2.

Figure 6: WoW avatar with advanced gear after unlocking content.

This changed after the addition of the transmogrification feature ("transmog") in patch 4.3.0 in 2011, which allowed players to alter the appearance or skin of any gear element to resemble other items that players have acquired. Suddenly, a tank’s avatar no longer always communicated their role or experience for group play. Players learned to rely more on a mechanical inspection system which could be used to determine the true name of an item, its transmogrification status, and also its in-game abilities. Manual party grouping in WoW was eventually supplanted by automated systems such as LFR/LFD (Looking for Raid / Looking for Dungeon) and also, finally, Group Finder.

Implications of Avatar Design for Curriculum Design

As noted in our introduction, there are several parallels between instructor and Game/Dungeon Master. With those similarities in mind, avatar/character choice can inform curriculum design decisions and a mannerist pedagogy that harnesses style-shifting, rapid revision and modulation based upon the individual needs of the students in a specific classroom.

In several of Jeff’s courses (particularly freshman composition and others), he tries to gauge a student’s initial written competency and outside interests by way of an early, low-stakes writing assignment, such as a personal manifesto or narrative. These writing exercises serve two purposes: they help Jeff gauge where his students are in their learning process and also understand their core interests, goals, and ideals outside of the writing classroom. After reading these written exercises, he tries to alter his curriculum--exercises, texts, resources--to meet the needs of that student body. This is not at all dissimilar from a GM’s mannerist-approach to adventure design (i.e., if I have a lot of fighters for a session, I might consider adding more combat encounters). This style-switching, adaptation, and modification based upon different groups of students, across different days and semesters, is facilitated by a mannerist pedagogy.

Jeff can imagine a way that avatars/character generation might be an even faster method for gauging the interests and capabilities of a class. Early on, a student might be tasked with designing their avatar as a method for introducing themselves to their classmates. Jeff might respond by developing a unique avatar for that class. Then, like in early iterations of WoW, a student might attain virtual gear that could suggest their roles, intentions, and what content they had already unlocked in previous courses. Imagine a course where a student’s mastery of a specific citation style would result in a physical object or accoutrement that’s readily visible to the instructor and the class? Working in tandem with knowledge gleaned from the Metroidvania case study presented later in this webtext, there could be a curriculum map that "unlocks" content based upon this mastery and provides items to further outfit a student’s avatar.

Furthermore, avatar construction can be used as an exercise that draws connections between rhetoric, design, and data visualization. Avatars are frequently constructed by hand and having students reflect on the rhetoric of their avatar’s appearance and what it means for their identity as a student, a writer, and person can be an important exercise in and of itself.

Implications of Avatar Design for Collaborative Work

As an instructor, Jeff has grappled with student dynamics in group projects and collaborative writing assignments. Nearly every semester that he teaches a course with a significant group assignment, students struggle to navigate intergroup dynamics, workload split, or communicating expectations for their roles in group projects. Students consistently object to group work and, from an instructor standpoint, collaborative assignments can be complex to manage; yet, it is impossible to ignore the importance of group work as a vital skill to student success and professional development: most students will work in fields that require deep collaboration on many levels and with diverse teams of professionals. The sooner that students learn to navigate group dynamics, the better.

Anecdotally, Jeff notes that students do not like group projects and often feel that they’re not a fair reflection of their individual efforts. He has tried to mitigate this problem with clear rubrics that note his expectations for group work, heuristics and resources meant to aid in the collaborative process, and reflective components designed to reinforce the importance of personal involvement in these projects. Problems with student collaboration and group dynamics are compounded in asynchronous, fully-online courses where students are not meeting regularly in person and real-time communication is relegated to platforms like Discord, Slack, and WeChat, which can be impersonal and limited.

None of Jeff’s pedagogical efforts have ever completely overcome the innate obstacles of group work. As a reflective practitioner, Jeff thinks it is important to note areas where his pedagogy can still improve: group projects are certainly one of these areas. Looking at his student evaluations and anecdotal feedback over the years, the main complaints are regarding the division of labor and expectations within the group structure. Some students are perceived to do too little--contributing very little to the group dynamic--and yet sometimes a single student may do too much. Particularly in creative projects with diverse team members, this leaves the group project feeling lopsided and lacking in true collaboration – the product of a single student’s vision and work.

If the goal of collaboration is to produce a group project where each member makes a significant contribution to the vision, direction, and workload, then communicating the needs of the project and the role(s) of the participants is key. In industry, stakeholders on a project will already have titles that clarify their team roles such as "project manager", "art director", "technical writer", etc. Students on a group project do not have the advantage of discrete career titles that serve to situate them rhetorically and/or communicate their talents or intentions for collaboration. Of course it’s possible that an instructor could develop hardcoded "titles" for the roles in a group project, but this may be too heavy-handed and stifling for creative projects, specifically multimedia projects that may take many forms, use numerous platforms, and require differing roles.

This is where WoW (2004) and D&D (2015) may present useful models in the form of avatar construction and a mannerist-approach to group dynamics. As discussed above, in both TTRPGs and MMOs, players’ imaginary or digital embodiment communicates their role to a playgroup quickly, effortlessly, and rhetorically. As an example, warriors in both games wear heavy armor and wield large weapons. Clerics affix their holy symbols and the relics dedicated to their deities. How their avatar looks – and the trappings that they carry – physically communicates their roles, intentions, and capabilities. Balanced groups form based upon these avatar choices and players in WoW and D&D are rarely confused about what they’re supposed to do to be successful in their group(s). Through the use of avatar, a DM responds with kairotic attunement to game design and the players respond with a mannerist approach to collaborative work to meet in-game challenges.

What if we could employ a similar system of avatar design for student work? As synchronous online classrooms and digital platforms evolve more advanced technology for materiality and spatiality, Jeff imagines a system where one’s avatar choice(s) might play a vital role in group dynamics for a collaborative project. A musically-inclined student might wear an instrument slung over their back. A student interested in filmmaking and editing could carry a camera or other equipment. Students could then group together with a similar mannerist-approach that we’ve seen for manual party groups in WoW. Additionally, Jeff could view these student avatars and adopt a mannerist pedagogy towards curriculum design and quickly revise/design assignments that fit the needs and interests of a student group.

In a hybrid classroom, students might be tasked with designing an avatar that "introduces" their skills and interests to the class as a preamble for a specific collaborative, multimodal assignment. Students could then see each other’s avatars and group up dynamically online to tackle the project with a mannerist-approach. For example, Jeff can imagine a scenario where a group that needs a photographer might seek out an individual that is adorned with a camera or other photography equipment. During the face-to-face class period, students could engage in reflective writing and discussion on the rhetorical choices informing their avatar design and aesthetic. Within the classroom environment, avatar design could go a long way to communicating interests and help to form expectations for student roles in group work, particularly for creative projects.

Avatar Design in Action: Storium and the MU*

Although we’re still a ways off from a future with ubiquitous VR and fully materialized courseworlds, Jeff has tried to experiment with encouraging a mannerist approach to narrative design with avatar in some of his upper-level creative writing classes. One notable example is how Jeff has employed avatar construction for students engaging in collaborative storytelling in his Interactive Fiction and Narrative (WRIT 3215) course at Kennesaw State University. Within this class, students engage in several creative writing projects with the goal of crafting highly interactive digital narratives. Here, Jeff’s students experimented with the digital platform Storium as a practice space for collaborative writing and storytelling.

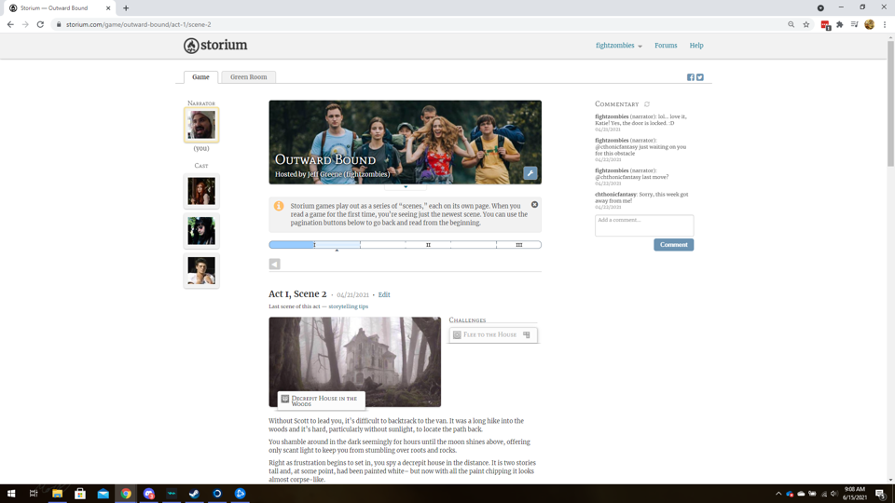

Figure 7: Storium scene setting screen shot.

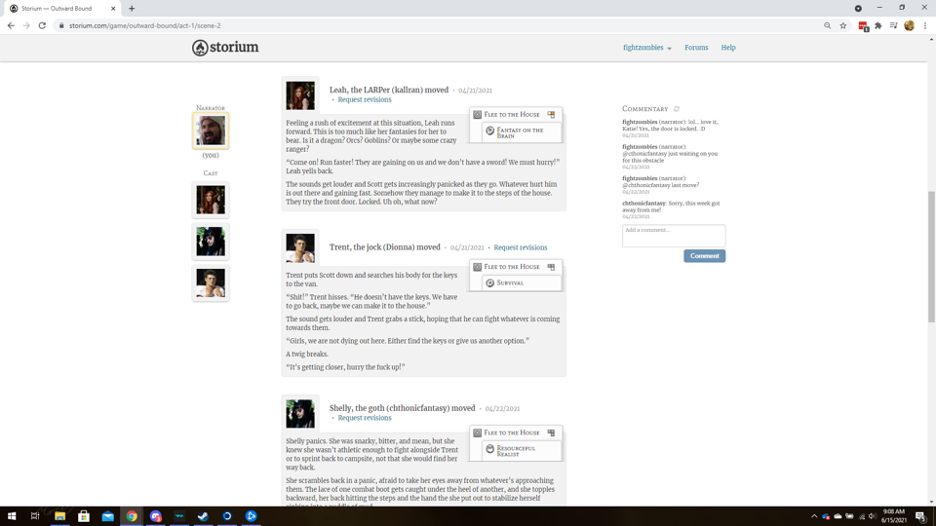

Figure 8: Players interacting in Storium.

Storium is an online platform that allows players to collaborate on text and image-based interactive stories. One player acts as the narrator (and maybe a character) and all the others adopt the role(s) of characters. Players take turns writing their actions, responding to each other, and evolving the story over a number of asynchronous posts. The game itself is decidedly rules-lite with a simple card-system for adjudicating task resolution, but unlike D&D’s top-down structure (Dungeon Master to Player(s)), Storium gives significant control to all players not unlike other rules-lite, narrative driven tabletop RPG systems like Fate (2003) or Apocalypse World (2010).

A game like Storium requires a mannerist-approach to narrative design from all players since the story is pushed and pulled in a variety of directions in real-time. Unlike D&D where the DM arbitrates most player interactions and directs the narrative with a high-degree of authorial control, Storium’s players have a great degree of mechanical control over the storytelling. Storium’s narrators, on the other hand, have a blended role that involves facilitation, experimentation, and coordination over narrative delivery. This egalitarian approach to storytelling requires a strongly collaborative environment as players respond to the evolving story and push it in interesting and unexpected directions.

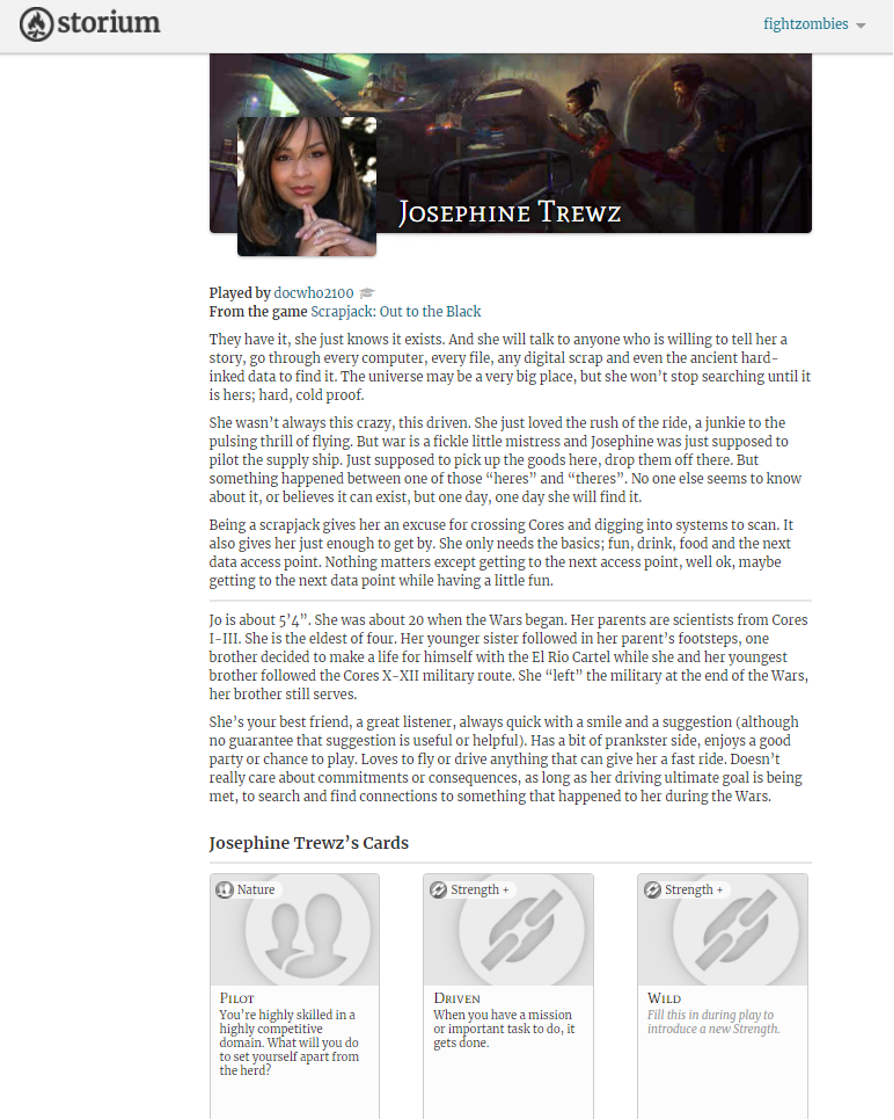

Avatar design in Storium is also a key component to how players communicate their intentions for the narrative. The core of avatar design in Storium starts by choosing visual images for a character (something Creative Commons licensed), writing backstories, and selecting playable cards that represent their character’s goals, aptitudes, and weaknesses. These cards have a clear mechanical effect on the story but also communicate players’ roles, intentions, and interests in the narrative. Like the characters generated for D&D, a character’s avatar--their material appearance, backstory, and selected abilities--reflects the kind of challenges they’re interested in overcoming and even the potential direction of the story.

Figure 9: An example of a Storium avatar.

In WRIT 3125, Jeff used Storium as a space for a series of low-stakes collaborative writing exercises and students were encouraged to reflect on the experience afterwards. In reflection, students often mentioned the need to be adaptable and flexible in their narrative design(s). Students also noted responding to the material avatar choices of their peers, often making narrative decisions and drawing on inspiration from the appearances and backstories of other characters in their groups. It’s interesting to note how students used the concept of avatar rhetorically to develop collaborative stories. In future courses, Jeff plans to assign Storium as a platform to design serious games and explore issues in social justice.

Jeff hopes to continue to experiment with the use of avatar and character generation in his upper level writing courses. In future courses, he may return to an even older form of text-based game with the MUSH (Multi-User-Shared-Hallucination), the classic telnet-based game/role-playing space. MU* platforms are entirely text-based but more closely mirror spatiality with "rooms", text-objects, and other elements of corporeality in a digital space. Here students can explore the rhetoric of avatar by creating "multidescers", a code object in the game that allows players to store and swap different appearances for different purposes. Students would employ a mannerist approach to their avatar design– designing swappable avatars for use in various rhetorical situations. Jeff can imagine a reflective exercise where students explore visual rhetoric and identity by creating multiple avatar appearances or skins for use in a digital world.