Home | Introduction | Case Study 1 | Case Study 2 | Concluding Thoughts | References

Case Study 2:

Spatial Design

Games such as Hollow Knight (2017) and Ori and the Blind Forest (2015) raise questions of learning and pedagogical design through their environments as symbolic-rhetorical spaces of meaning-making (Murray, 2012; New London Group, 1996). These games are an example of the "Metroidvania" genre (Nutt, 2015; Rodriguez et al., 2018), in which the game world is open for nonlinear exploration, but players must learn new skills to progressively unlock and explore new areas. They may need these skills to physically reach another area, for example, or to clear obstacles such as bosses and other opponents. In an online asynchronous course, content does not necessarily need to be navigated sequentially. Like a Metroidvania-style game, courses could be designed to enable students to navigate at their own pace based on their interests and goals. This case study examines the opening-level mechanics of Hollow Knight and Ori and the Blind Forest to determine how they employ aesthetically pleasing, narratively engaging environments that motivate players to unlock new areas by developing new skills. We then consider how these spatial design practices might inform the design of asynchronous online courses.

Overall, we suggest, when it comes to spatial rhetorics, a GM/instructor as mannerist-rhetor invites students/players to co-create shared conceptual spaces, in designing their learning experiences. Specifically in an online asynchronous course design, the GM-instructor uses nonlinear affordances of space and Metroidvania-inspired cumulative wayfinding principles to encourage students to reflect on and chart their own courses in ways that build up connections between various skills, and then create maps of those paths accompanied by reflections to account for their learning at the end of the semester.

Interface, Metaphor, and Embodied Pedagogy

This case study explores possibilities for using games’ spatial materialities as organizing systems for structuring pedagogical interfaces in mannerist ways that invite students into the process of negotiating and co-shaping these places based on their individual learning experiences. These maps offer a shared space for negotiating with symbol systems, skills, ideas, and connections between key concepts; the map serves as an interface metaphor that invites a certain kind of behavior (exploration and discovery) from the user or student. We offer analyses of games’ material spaces that provide generative pedagogical insights; highlight ways these spaces build on strong pedagogical practices and theory for embodied learning in the field; offer connections to pedagogical practices heading in this direction; and highlight implications for more fully developed pedagogical practices inspired by these principles.

The pedagogical approach developed in this case study is grounded especially in Patricia Dunn’s (2001, 2021) and Particia Dunn and Kathleen Dunn De Mers’ (2002) work on incorporating multiple media channels into writing pedagogy for inclusive learning environments, particularly through metaphorical thinking; in James Paul Gee’s (2007) work on the strong learning principles implicitly built into the design of video games; and in Jessie Borgman and Casey McArdle’s (2019, 2021) work on designing for user experience in online writing courses, including interface aesthetics. In this case, "playing well" (and learning well) invokes two parallel sets of responsibilities: first, the instructors’ responsibility to design an engaging learning space that incorporates multiple channels of interaction and meaningful decision-making; and second the students’ responsibility to engage in potentially unfamiliar learning spaces guided by their own goals and interests, while seeking and providing assistance for other course members attempting to navigate similar paths.

Games’ material affordances as design models offer one way of getting out of "conventional drafting routines" (Dunn, 2001, 59) and encourage instructors to consider other ways to design/deliver knowledge/information in online course contexts. A well-chosen spatial metaphor is a powerful instructional and synthesizing tool in classroom contexts, which instructors can incorporate into course interface design via game maps as models. The instructor engages in and invites students into intellectual play through the design of online course spaces as interactive environments for exploration and discovery.

This approach offers challenges and possibilities for pedagogical delivery as well, by encouraging instructors to use games’ spatial-material rhetorical strategies to help them incorporate new ways of knowing and making knowledge beyond writing into their pedagogical design and delivery practices. We use the material rhetorics (Rickert, 2013) of games as design models to seek options for building more inclusive pedagogical interfaces that challenge, contrast, or otherwise think outside the box of expectations/assumptions of what an online course interface should look like.

A map as a pedagogical structuring system offers a space-based interface design as another way of engaging students. It provides a way of synthesizing learning and highlighting interconnections between course material, by making underlying metaphors and connective systems visually explicit for students and instructors alike. A learning interface grounded in spatial metaphors offers a particular way of mapping out problem-solving sequences and activities onto spatial dimensions.9

In particular, Amy Propen (2012) helps us connect mapmaking to mannerist pedagogy through a critical cartography-based approach to space, place, and visual-material rhetorics. Propen draws on de Certeau to frame "space" as a "practiced place" (de Certeau 117, qtd in Propen, 20120, p. 5). A space is transformed into a place by its "walkers," or "the subjects residing within a place" (Propen 6). If a space is transformed into place by its "walkers," then students as wayfinders can shape a course "space" into a "place" through creating reflective maps that trace their navigation and learning experiences. Stepping into the inventive role of spatial co-designer alongside the mannerist GM/instructor, the students’ interactions with the course-map are what turn the course space into a place by giving it experientially-based meaning grounded in their own unique configurations of learning engagements.

Specifically, Propen (2012) identifies mapping as a practice that "invites participation and dialogue," one that "that can shape knowledge, reflect power dynamics, and serve as a means for advancing social change" (7). Putting maps at the explicit center of the course design opens up the mannerist pedagogical possibility of inviting students into the agentive, inventive practice of mapping out their understanding of the course as co-creators/co-designers of the course space. Within this framework, designing a course-map and inviting students to map out their experiences draws on the power of mapmaking to provide a synthesizing symbolic overview of a given place, rather than a more concrete, embodied situation within or experience of a particular space-place. We suggest that this emphasis on co-creation and navigation of space as symbolic overview, rather than aesthetic dimensions of embodied situatedness, better connects games’ spatial-material rhetorics (especially those of Metroidvania-style games) to the affordances and constraints of university-sponsored course management systems.

Game spaces offer invention resources to help instructors choose meaningful metaphors to synthesize learning and make underlying interconnections between content more transparent in designing pedagogical interfaces, to help them create a shared conceptual space based on embodied metaphors rather than abstract principles selected by the instructor (or by the LMS designers).

Spatial navigation offers multiple routes through course material rather than a single predetermined path. It suggests a number of possible approaches to complete an activity; the instructor can offer suggestions, but ultimately students decide how to complete assigned tasks and in what order, or how to apply the skills they’ve learned to a complex, multifaceted activity with no one right answer. This is a particularly useful skill in helping students prepare for professional writing practices in workplaces with complex problems requiring multi-step problem solving without necessarily clear guidelines for completion.

We want to recognize that the work of interface design along with other less familiar instructional materials requires a significant amount of labor on the instructor’s part (and may not always be possible depending on the instructor’s institutional context and online course delivery requirements). However, we suggest this significant shift may open up new spaces for learning, if framed clearly and reflectively, by visually reframing the course’s operating assumptions from the ground up. We acknowledge the limitations of space when it comes to practically designing space-based encounters in asynchronous online courses, especially if instructor’s are working within the constraints of a university course management system like Brightspace or Canvas. Here we suggest small, key changes that we hope will be more sustainable to implement, with potential for building into a broader overhaul given time, resources, tech support, and pedagogical support.

Ultimately, spatial rhetorics may highlight one key area of distinction between instructors and GMs; when it comes to designing an interactive pedagogical space with institutional resources, for example, an instructor faces far more limitations than a GM, whose spatial design practices are limited primarily by breadth of imagination. However, instructors can still learn much from GMs and game design maps to consider small but impactful changes to course design in ways that invite students to co-create the learning experience in new, reflective, and inventive ways. Game-based spatial rhetorics can support mannerist pedagogical practices of working to build more of a "sense of place" and agency of navigation into what’s otherwise a highly temporally-based and physically-abstracted interface. In our next section, we focus on the specific genre of Metroidvania games as inspiration for how instructors and students alike might inventively engage with the spatial rhetorics of online course interfaces.

Metroidvania as Game Genre

The word "Metroidvania" is a portmanteau coming from the titles of the games "Metroid" and "Castlevania," two early classic versions of this style that set the form for games in this genre to come. The principle of a Metroidvania-style game is to start with a character in a limited location, then to slowly expand the game’s map and accessible territory out further through ongoing quests and overcoming obstacles. Furthermore, some areas of these games are inaccessible at first and appear to be insurmountable, until players gain a skill or ability in some other section of the game. The game thus encourages iterative play, in which a character can return to certain areas to gain bonuses, points, or rewards not previously accessible if driven by completion-based principles. (For more on Metroidvania game genre and mechanics, see Nutt, 2015, and Rodriguez et al., 2018).

Metroidvania-style games raise interesting possibilities when considered from a pedagogical standpoint. They offer a principle of starting from the known, or a small space, and expanding that territory out by exploring the unknown. They encourage players to make connections between smaller segments whose relationships may be difficult to see on the immediate level, but that make sense on a broader level when the full view is revealed. Thus, their spatial materiality and design inspire learning by offering this full synthesizing view of a space that demonstrates interconnections, or invites players to expand further by indicating what unexplored territories still remain to be discovered.

Along with this space-based synthesizing view, Metroidvania games also inspire learning by iterative, recursive play that unlocks new areas by developing skills (practices closely connected to mannerist pedagogical values and strategies). In this sense, exploration can be nonlinear and freely player-driven, but narratively or sequentially guided based on the abilities players have developed. Furthermore, these skills can build on each other in combination to require complex combinations and syntheses that continuously challenge players to put into practice what they’ve learned. This scaffolding can help players develop a sense of growing mastery and expertise, while giving them further access to various sections and rewards of the map. Thus, this aspect of Metroidvania games inspires learning insofar as players must continue to move forward in the game and develop or unlock new skills if they wish to continue, and gives them an increasingly complex, multifaceted set of tools with which they can interact with their game environment, and therefore must select from and apply strategically.

At the same time, there are risks – if the combinations of skills players must learn and/or apply are too challenging to progress to the next step of the narrative, story, or space and offer no workarounds, players may become discouraged and disengage with either the game or the learning environment. Care must therefore be taken on both accounts/dimensions to 1) make the spaces engaging and interesting to explore for their own sakes and 2) to offer plenty of guidance/support/scaffolding to help players learn what they need to keep moving forward rather than getting stuck and shutting down.

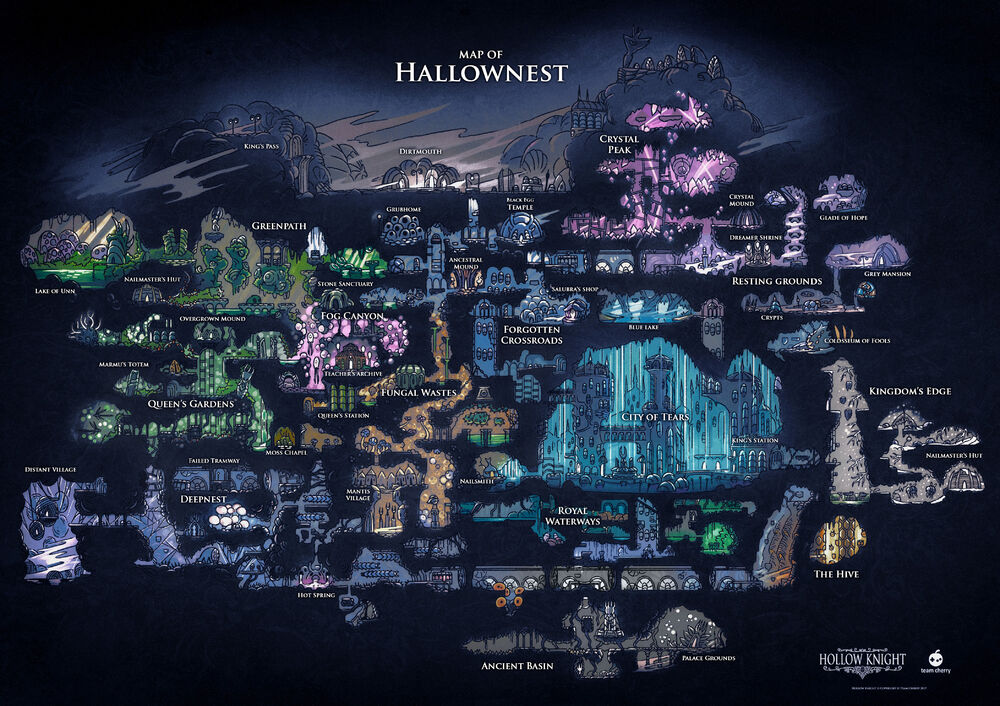

The next section discusses two examples of recent popular Metroidvania-style games: Hollow Knight (2017) and Ori and the Blind Forest (2015). The first two sections introduce the games; highlight their Metroidvania-style logics (including key similarities and differences); foreground several points of particular connection to pedagogical scaffolding; and share examples of video walkthroughs and world maps. The next section shares an overview for a course map inspired by these games’ wayfinding, cumulative skills-based organizations, followed by additional takeaways for Metroidvania-inspired pedagogical scaffolding, then closes out briefly with potential further directions for exploring mannerist pedagogical strategies grounded in game-based spatial rhetorics.

Example 1: Hollow Knight

Hollow Knight was developed by Team Cherry in 2017 via Unity with hand-drawn illustrations. It features an unnamed main character with a skull-like headpiece in a world of bugs, rocks, and bones. In the opening level, the main character stumbles through the woods and lands in the Forgotten Crossroads and receives small clues to an ongoing trouble, though no further details. The character must go down a well and gather geo-coins; however, the map and territory remain unrecorded until the character meets with a mapmaker and can purchase new sections of a map, which are added to each time the character reaches a save point after further exploration. One of the skills developed is "Vengeful Spirit," gained in an early level from the "Snail Shaman," which makes it possible to defeat enemies who were previously impassable and thus gain access to new spaces. (As one fan-created walkthrough notes, "With the Vengeful Spirit Spell, the Elder Baldur blocking the way to Greenpath can be killed. This is the intended way to access the rest of the areas in the game" ["Vengeful Spirit"]). Each game section also provides a clearly distinct visual/aural aesthetic and "sense of place"; the Forgotten Crossroads section is a dark mine, for example, heavily featuring rocks and mining equipment, while Greenpath is a lush, airy forest with more natural-style lighting. These aesthetic differences provide a clear "sense of place" as players move between sections of the map, which aids both in wayfinding and in overall affective engagement.

The driving narrative is not immediately clear, however; the character finds hints and pieces of the world and what’s going on through the space and interactions with characters, but the initial implicit motivation is to explore the environment and learn to pass new enemies rather than to necessarily complete points in the story. It is a challenging game in that save points are few and far between, and punishing in that although there are several lives, it is easy to lose them, and every death results in a total loss of geodes, the game’s form of currency. (You can reclaim geodes by returning to the spot where you died and reclaiming your specter, but with save points being so far between, that can often be an arduous journey).

Figure 10: Map of Hallownest (from Hollow Knight fandom wiki)

Figure 11: Hollow Knight Walkthrough from Gamer Walkthroughs.

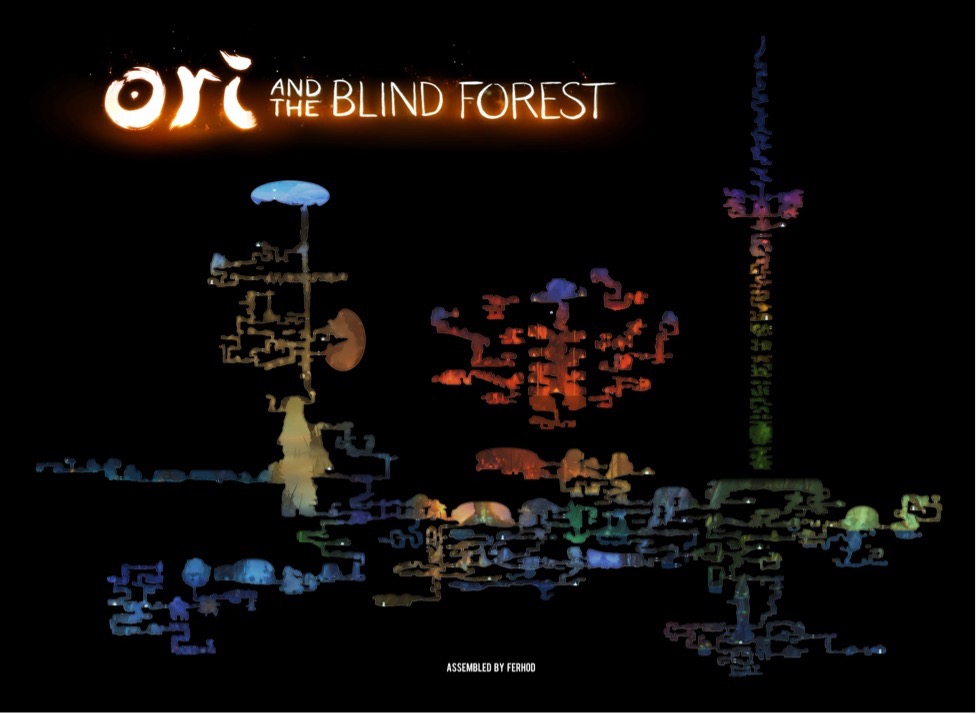

Example 2: Ori and the Blind Forest

Ori and the Blind Forest was developed by Moon Studios in 2015 (and more recently followed by Ori and the Will o’ the Wisps in 2020). It is lovely and atmospheric, with lush forest settings and evocative soundtracks, and features Ori, a small creature seeking to heal a magically blighted forest in order to return to its home tree. The narrative progresses through movement into new sections of the forest, each with their own sets of environmental perils. Progressively gained skills include double jumping and targeted slingshots, which are granted following the completion of key segments and when transitioning into new areas of the map. The game also offers spaces for players to practice these skills safely before moving out into a high-stakes setting. Furthermore, Ori and the Blind Forest (2015) offers clear aesthetic and challenge-based distinctions in each locale; the Moon Grove, for example, is characterized by deep twilight shadows, while the path to climb up the Ginso Tree features numerous thorns that players must navigate via a newly gained double-jump feature that continually challenges their attempts toward vertical progress.

Like Hollow Knight (2017), Ori and the Blind Forest (2015) offers an expanding map each time players move into a new space. However, unlike Hollow Knight (2017), players do not need to buy the map—it is an automatically updating feature. Furthermore, the saves are much more flexible—players can save up energy to create a save point wherever they’d like, which makes it much more customizable and forgiving to retry tricky places without needing to trek too far between saves. This game encourages exploration of unvisited spaces, with iterative options for completion once new abilities unlock increasing access to spaces, but there is a broader narrative arc threaded through players’ movement to each space in a way that highlights an explicit storyline revealed through ongoing exploration.

Figure 12: Map of the Forest (from Reddit/Imgur)

Figure 13: Ori and the Blind Forest Walkthrough from Gamer Walkthroughs.

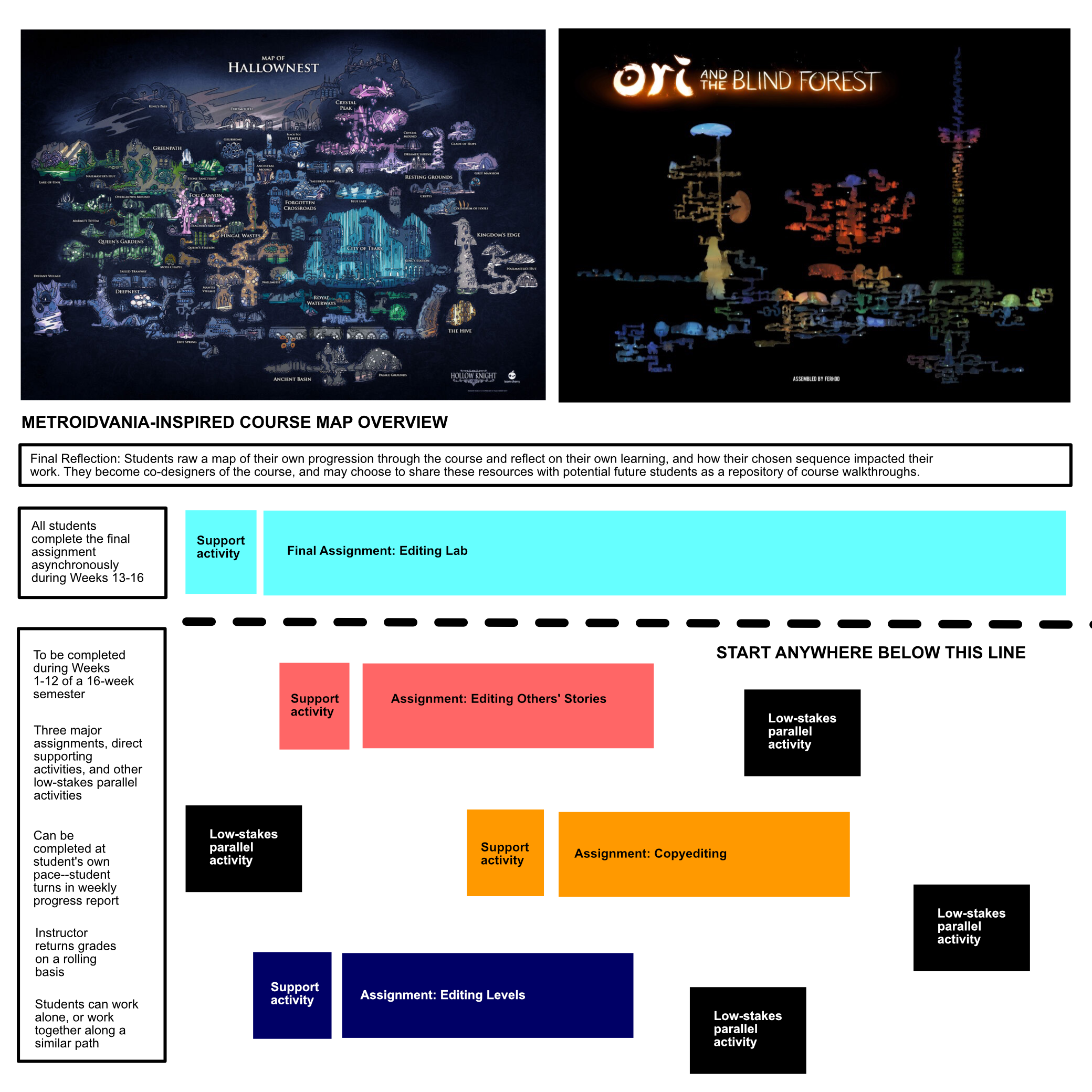

Metroidvania-Inspired Course Map

Inspired by the wayfinding spatial logics of Metroidvania-style games such as Hollow Knight (2017) and Ori and the Blind Forest (2015), Erin offers one possible diagram for an online course map that offers similar navigational structures based on "wandering" rather than predetermined sequence, and that invites students into the mannerist-style invention and design processes of charting their own routes through the content in ways that invite them to actively shape and reflect on their learning experiences. This potential course map draft below offers a simplified spatial overview of a Metroidvania-style course that invites students to actively reflect on their decisions and experiences of charting a path through the course. The organizing spatial (rather than temporal) logics invite students into the role of co-designer as mannerist-rhetors in shaping their learning and helping each other (along with future students) chart their way through the course materials.

Overview of Metroidvania-style course map inspired by game maps for Hollow Knight (2017) and Ori and the Blind Forest (2015).

The course diagram above offers an adapted version of Erin’s undergraduate Professional Editing Course, which involves four major assignments sequences supplemented by direct support activities interspersed with other short-term, lower-stakes assignments. In a course driven by the spatial logics of Metroidvania-based wayfinding, students can complete the first three major activities over the first three months of a fifteen-week semester. These activities can be completed at the student’s own pace and based on their interests in sequencing the materials. Students are responsible for turning in weekly progress reports accounting for the status and rationale behind the activities they’ve created, and the instructor returns grades on a rolling basis. Students can choose to work alone in charting their path through the course, or they might form small groups based on similar interests, learning styles, and support needs. During the final month of the course, all students apply the skills they’ve developed during the first segment of the course to a comprehensive final assignment that draws on the full breadth of experience they’ve developed up to that point.

At the end of the semester, students submit a map of their own progression and selected route through the course and reflect on how their chosen sequence impacted their work and their learning experiences. The instructor can use this feedback to shape the overall map of the course and, with students’ permission, share these individual maps with future students as a repository or "course walkthrough" to guide other students looking to chart their own path through the course with mindfulness toward avoiding pitfalls and aiding progress. This reflection especially foregrounds the mannerist-inspired rhetorical potential of Metroidvania-style course design in which students are invited to become co-designers of their own learning experiences: to self-reflectively follow their intuition by responding to the content, their classmates, and their own interests and learning goals/styles; and to actively map out their decisions to account for how the interconnections they’ve mapped out have generated a unique experience that shapes their overall learning for the course.

We acknowledge that this skills-based "unlock point" in this Metroidvania-style course design is extraordinarily simple compared to the branching, sweeping, heavily organic maps of Hollow Knight and Ori and the Blind Forest. The simplicity at this stage is meant to support ease of adaptation to a new organizational system for students and instructors alike, in ways that make the labor of course management and assessment sustainable for the instructor and that lower the learning curve for students. Once a foundation and familiarity with the course structure has been established, the instructor can create increasingly nuanced skills-based "unlock points" in response to students’ reflective maps and accounts of navigating the course.

Other Pedagogical Takeaways for Metroidvania Case Studies

Metroidvania-style games such as Hollow Knight (2017) and Ori and the Blind Forest (2015) offer several additional takeaways when considering the design of online course progressions and spaces.

First, students might learn several low-stakes skills in a variety of settings and activities. They might choose the order in which they learn these skills and complete these activities themselves, then come together for more complicated tasks later on in which they must combine these skills for a more complex task. This could be set up in an online space with prerequisites to access new areas of content, which then allows students to expand out to further levels of the course depending on the choices they’ve made and what they’ve completed up to that point.

Second, instructors might offer a synthesizing spatial overview of the relationships between course content and how each module builds on the next, as a way of visually and spatially mapping out the course’s overall conceptual architecture. This would give students a checkpoint and a way to touch base as they complete each level—to guide their progress, help them situate themselves in the course, and help them know what they need to do in order to get where they’re going. Although students might complete the course in the order they wish to do so, course community and peer mentorship might be offered through a "tutorial"-style section in which students share with one another how they solved various tasks in order to get to the next level. Care would need to be taken with assignment design to ensure academic honesty; however, in multiple online gaming communities (including Metroidvania-style games), player-generated walkthroughs and maps play an important role in supporting other players’ success by demonstrating effective solutions to challenges such as wayfinding, puzzles, and other obstacles. (See for example player-generated walkthroughs for Hollow Knight (2017) and Ori and the Blind Forest (2015).) In this context, tutorials help players learn from their peers and consider multiple potential solutions for solving problems. However, players themselves are ultimately responsible for enacting these solutions in their own gameplay, as students are likewise responsible for demonstrating their own learning. Along with tutorials shared among classmates during the class, students’ final reflections mapping out their selected routes through the course might serve a similar support function as walkthrough guides for future course participants.

Additionally, instructors should strive to create a unique "sense of place" to support wayfinding between each unit. This may not go so far as concrete physical attributes per se, but clear aesthetic distinctions between each unit so students know "where they are" as they move back and forth between units. This approach builds on Borgman and McArdle’s (2019) attention to "aesthetics and sensory experience" as an important part of fostering personal engagement in online course development (p. 20), as well as principles in the Dungeon Master’s Guide (2014) of giving each space a unique environmental character to increase player engagement (p. 106).

Finally, building in plenty of "save" points along the way to customize assistance at various pain points would help students learn new skills through numerous repeated attempts to improve, rather than punishing them by taking away points or other assistance when faced with a difficult new skill in which performance is initially low. Building in plenty of low-stakes check-ins to build up skill, as well as opportunities for revision and continued feedback, might also be a parallel function in an online writing course.

Connections to Current Teaching Practices

Although it is beyond the scope of this case study to present a fully-developed and user-tested course interface, Erin is taking small steps in the design of her asynchronous courses to work towards this more ambitious goal. In her online courses, content is chunked out into recommended Overview/Monday/Wednesday/Friday breakdowns to suggest one path through the content; however, all course materials are not actually due until the end of the week on Sunday at 11:59 pm. This setup offers both structure and flexibility for how students want to engage the course materials, and they have commented in informal responses that this organization appeals to them.

Some of these ideas are already built into pedagogical best-practice recommendations such as scaffolded learning; students and external peer course observers alike have commented how each course unit continues to build on previously developed skills in ways that provide both individual flexibility and support. In Erin’s professional editing class, for example, the opening units provide different editorial strategies and frameworks, and then the final unit is a long-term writing project and set of editorial exchanges. Students must decide how to apply the skills learned in the first unit to navigate their unique editing and writing situations in conversations with their partners—there is no one single correct route, and students are largely responsible for structuring their own editing exchanges in their assigned groups.

A Note on Other Online Game Spaces

These Metroidvania-style case studies and pedagogical takeaways are suggested with an asynchronous course design in mind, in which the instructor designs the space but leaves the responsibility for traversing it entirely in students’/players’ hands. However, for instructors interested in more synchronous online game spaces with strong tech support and options for creative flexibility (particularly in line with the introduction and first case study’s emphases), online spaces such as Roll20 in combination with content and character design support through D&D Beyond provide one possibly viable alternative. There has been increasing anecdotal pedagogical interest in using Roll20 as a teaching platform with the recent shift to virtual learning (DaniellaSantina, 2020; Shutts, 2021), and we suggest a need for further exploration into the possibilities of Roll20 (and similar platforms) as a teaching tool for its spatial-material and multi-channel interactive learning affordances.

Likewise, future studies may explore processes of inviting students into the process of co-creating and cultivating specific aesthetic dimensions of shared online course spaces. From an interface design metaphor and open-navigation perspective, for example, Erin developed an initial working model in preparation for a graduate course on web content development taught in Fall 2021 (Bahl, 2021). The spatial metaphor employed was a garden; students were invited to cultivate their own individual plots as the garden’s co-designers. With Thomas Rickert’s (2013) work on ambient spatial rhetorics in mind, we suggest there are rich mannerist-based rhetorical implications to explore in inviting students to co-design not only their paths through course materials, but the actual aesthetics of shared online course spaces in ways that support learning through affectively engaging environments tailored to students’ unique learning experiences and goals.

Footnote

9. For further discussion on intersections between spatiality, embodiment, and visual-material rhetorics, see Amy Propen (2012).