Multiliteracies

The survey was also designed to measure if a multiliteracies approach to digital literacy is being employed at the level of program administration. My purpose for considering this was to determine if programs are embracing the multi-faceted nature of digital literacy or if programmatic commitments are biased towards a particular approach. In other words, looking for biases towards one or more multiliteracies approaches in programs’ instantiations could reveal ways to better approach technology integration or to broaden understandings of the potentials for digital literacy in composition curricula.

|

Click the buttons toward the top of the chart above to see how the multiliteracies ranked, Hover over individual semi-circles to see percentages.

|

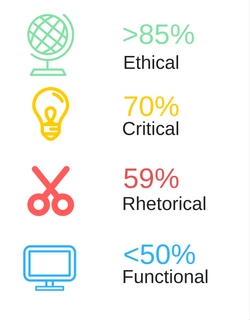

These concerns were measured in survey question 8, which asked respondents to examine definitions of rhetorical, critical, ethical, and functional digital literacies (summarized from Coley and Selber’s texts) and to indicate if they agreed that their program has a responsibility for teaching these literacies. The categories were defined as follows (but not categorized as rhetorical, ethical, and so forth in the survey):

Functional: It is the responsibility of my writing program to teach students how to use digital technologies in order to achieve educational goals, to effectively manage online workspaces, and use advanced software, web-based programs, and/or apps. Critical: It is the responsibility of my writing program to teach students to become informed questioners of digital technologies, to question the political and social assumptions of these technologies, and to question the ideologies that shape technology. Rhetorical: It is the responsibility of my writing program to teach students how to produce in digital environments, which includes understanding and learning how to capitalize on the persuasive abilities of design and to reflect on their design choices. Ethical: It is the responsibility of my writing program to teach students to be aware of the values of the audiences for their electronic compositions, to teach them to respect others' work and ideas in electronic environments, and to cite them correctly. |

Over 85% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their writing program should teach students the ethical components of digital literacy, and 70% aligned with the critical. A majority (59.42%) also indicated their programs are responsible for the rhetorical component of digital literacy. On the other hand, less than half of the WPAs indicated that it is their program's responsibility to teach students the functional aspects of computer literacy, such as learning how to use certain apps and programs.

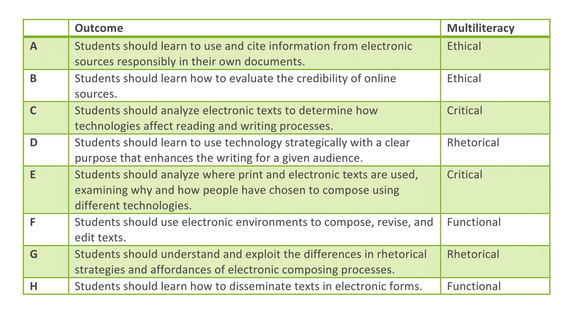

I also took specific student outcomes from the WPA Outcomes Statement (version 2.0) and Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing and asked the respondents to rank these outcomes based on the level of importance to their program’s mission and goals (survey section 3 question 5). The goal here was to force a hierarchy of principles and practices with regard to functional, critical, rhetorical, and ethical literacies.

I also took specific student outcomes from the WPA Outcomes Statement (version 2.0) and Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing and asked the respondents to rank these outcomes based on the level of importance to their program’s mission and goals (survey section 3 question 5). The goal here was to force a hierarchy of principles and practices with regard to functional, critical, rhetorical, and ethical literacies.

To design the question, I consulted the Outcomes Statement and Framework to examine the student outcomes delineated as important by these WPA-driven documents. I used two outcomes that aligned with each literacy—functional, critical, rhetorical, and ethical—and asked respondents to rank these from least to most important (1-8), choosing each number only once. (While the categories are listed in the table below, you can also click here to see a more in-depth explanation of how the categories were created.)

The categories that received the “most important” ranking most often were D (22.58%) and F (20.97%), with B close behind (16.92%) (n=69). No respondents selected H as most important, and for least important, again, H stood out, with 51.56% of respondents ranking it as least important. C was also ranked low in importance. These data suggested that the rhetorical skill of learning to use technology strategically with a clear purpose that enhances the writing for a given audience was the student outcome most important to the overall goals and missions of these respondents’ programs. This aligned well with the earlier finding that WPAs are motivated to implement digital literacy in order to serve rhetorical ends and enhance written communication. Also important was a functional skill—using electronic environments to compose, revise, and edit texts (F). However, the other functional skill of disseminating texts in electronic forms was not important. This makes sense since the first functional skill focuses more on the writing process, which was important to WPAs in other parts of the survey, whereas the second is a technical skill to circulate writing. Also important was the ethical ability of evaluating the credibility of online sources. This is consistent with the high ranking of ethical digital literacy in question 8. With the critical category, programs value teaching students to analyze where print and electronic texts are used and examine why and how people have chosen to compose using different technologies, more than teaching students to examine how electronic texts affect reading and writing processes. Other than functional ranking low, there weren’t clear distinctions between rhetorical, critical, and ethical.

While the goal was to force priorities with this question, the findings may be limited when interpreted on their own because, as some respondents suggested, some categories overlap or may carry similar levels of importance. I therefore included an open-ended follow-up question that would shed additional light on the trends delineated in the quantitative data, asking WPAs to describe their process in ranking these outcomes.

Most respondents’ explanations for their ranking focused on choosing the outcomes that were most similar to traditional writing pedagogy goals—or outcomes common for alphabetic texts. As one respondent stated, “I put as most important the tasks that are specific to general literacy skills (analyze texts and their technologies so as to use them in their papers effectively and responsibly).” A similar response was: “I selected as most important the choices that help students achieve in traditional writing contexts—research and analysis.” Others indicated that questions focusing specifically on the technology were ranked lower because thinking about “genre” and “audience” is important for all students and should transcend medium. Thus, the theme of digital literacy being a means to achieving the traditional goals of writing courses and a means to rhetorical ends carried through these responses.

Many stated they were less concerned with production or dissemination than with the other categories. Also, similar to the implementation findings, respondents indicated that practice in critically reading and analyzing electronic texts is more important than creating them. However, this was generally not because they did not value composing but because of time constraints and/or faculty expertise.

The categories that received the “most important” ranking most often were D (22.58%) and F (20.97%), with B close behind (16.92%) (n=69). No respondents selected H as most important, and for least important, again, H stood out, with 51.56% of respondents ranking it as least important. C was also ranked low in importance. These data suggested that the rhetorical skill of learning to use technology strategically with a clear purpose that enhances the writing for a given audience was the student outcome most important to the overall goals and missions of these respondents’ programs. This aligned well with the earlier finding that WPAs are motivated to implement digital literacy in order to serve rhetorical ends and enhance written communication. Also important was a functional skill—using electronic environments to compose, revise, and edit texts (F). However, the other functional skill of disseminating texts in electronic forms was not important. This makes sense since the first functional skill focuses more on the writing process, which was important to WPAs in other parts of the survey, whereas the second is a technical skill to circulate writing. Also important was the ethical ability of evaluating the credibility of online sources. This is consistent with the high ranking of ethical digital literacy in question 8. With the critical category, programs value teaching students to analyze where print and electronic texts are used and examine why and how people have chosen to compose using different technologies, more than teaching students to examine how electronic texts affect reading and writing processes. Other than functional ranking low, there weren’t clear distinctions between rhetorical, critical, and ethical.

While the goal was to force priorities with this question, the findings may be limited when interpreted on their own because, as some respondents suggested, some categories overlap or may carry similar levels of importance. I therefore included an open-ended follow-up question that would shed additional light on the trends delineated in the quantitative data, asking WPAs to describe their process in ranking these outcomes.

Most respondents’ explanations for their ranking focused on choosing the outcomes that were most similar to traditional writing pedagogy goals—or outcomes common for alphabetic texts. As one respondent stated, “I put as most important the tasks that are specific to general literacy skills (analyze texts and their technologies so as to use them in their papers effectively and responsibly).” A similar response was: “I selected as most important the choices that help students achieve in traditional writing contexts—research and analysis.” Others indicated that questions focusing specifically on the technology were ranked lower because thinking about “genre” and “audience” is important for all students and should transcend medium. Thus, the theme of digital literacy being a means to achieving the traditional goals of writing courses and a means to rhetorical ends carried through these responses.

Many stated they were less concerned with production or dissemination than with the other categories. Also, similar to the implementation findings, respondents indicated that practice in critically reading and analyzing electronic texts is more important than creating them. However, this was generally not because they did not value composing but because of time constraints and/or faculty expertise.

|

Research also carried heavy weight in this question. Over 60% of the respondents described research as important to their ranking process, stating their program cares about students being able to use online sources. A few respondents stated that students need to use sources ethically, and one stated programs should be sure “students know how to cite so that they don’t end up inadvertently being charged with academic dishonesty.” While evaluating the credibility of online sources was ranked highly in the quantitative data, most respondents took a more functional approach in the open-ended answers, describing computers as research tools.

|

While the quantitative data showed that critical digital literacy is valued over rhetorical, the open-ended answers revealed that WPAs tend to interpret technologies as the electronic texts students analyze in a course, such as a You Tube video, as opposed to computers or programs used to create these texts. Only two respondents mentioned in an open-ended response—throughout the entire survey—that students are encouraged to question the technologies they (or others) use to compose. Selber (2004) maintained that students should be encouraged to ask what cultural and/or political values are embedded in technologies so they can become social critics as opposed to “indoctrinated consumers of material culture” (Selber, 2004, p. 95), and I would argue based on the survey responses that these kinds of questions are not typically being asked in the writing programs surveyed for this study. Similarly, some respondents noted technology is often invisible in their own programs, and others indicated that analyzing how technologies affect reading and writing processes was not as important as other literacies.