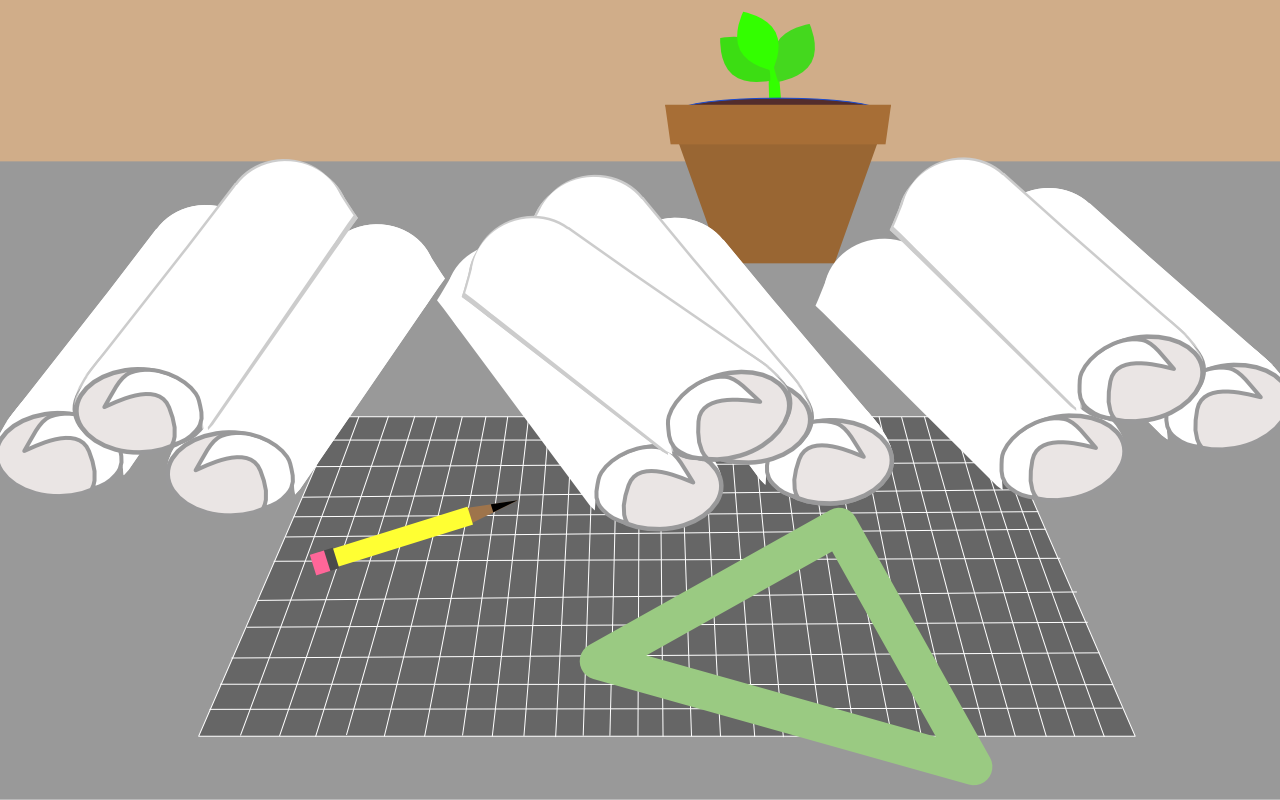

The "blueprint" (loosely categorized here as a conceptual draft or diagram for constructing a space) is not a metaphor theorized explicilty in Sustainable Learning Spaces: Design, Infrastructure, and Technology. Rather, it is evoked by the collection's visual-verbal documentation of in-progress spaces, and by the way the authors draw on their stories of developing sustainable learning spaces. Each document on the desk briefly summarizes the authors' suggested "takeaways" for sustainable practices based on their own experiences of the process. This presentation foregrounds one of the editors' desired impacts for the collection: to provide localized reports of best practices for creating, reinventing, and sustaining learning spaces, with the hope that these stories might be useful for others' further endeavors (Epilogue). Like the documents represented as resources for further drafting , this collection's thorough narratives of localized processes seem especially of interest as a set of models for faculty, staff, and administration members looking to develop their own sustainable learning spaces.

There are some critiques embedded in this organization for the sampled elements as well. This collection was overall less focused on webtext craft than Reconstructing the Archive or Techne (perhaps a more sustainable practice when implementing a collection across ten different sets of contributors). Thus, the representative documents all take more or less the same form of a block of text with an embedded image. The documents can also be a bit challenging to navigate across outside of their respective piles; I had difficulty gaining a sense of the overall "sense of place" within the webtext based on its navigation, which provided a table of contents for each section but never for the collection as a whole. Finally, like the three stray magpie feathers in the left corner, the blueprints offer a set of isolated takeaways but not necessarily an overarching, cumulative takeaway; likewise, a synthesizing editorial voice to put the chapters in dialogue with a set of cumulative best practices at the end could have been a useful resource for further discussion and future reference. Despite these critiques, however, this presentation ultimately speaks to the value of the collection as stories of authors' making in their localized institutional settings, as guides for the readers' own pursuits, and as invitations to continue the conversation in their own space-making practices.